So many successful tech products get called “iconic” these days that the honorific has been seriously devalued. In the case of Apple’s iPod, however, it’s a perfect fit. And if you conjure up a classic iPod in your mind, you’re probably envisioning several things, each iconic in their own right.

There’s the sleek front—white plastic in its most familiar form—and stainless steel back. The scroll wheel that made it practical to whip through hundreds or even thousands of songs. The small display that initially displayed only monochromatic text in Chicago, a typeface that dated back to Apple’s original Mac.

For Tony Fadell, however, memories of iPods are just as likely to involve their insides. Fadell is one of the creators of the iPhone, the cofounder and former CEO of Nest, a busy investor, and—as of this month—a book author. But he’s probably most often described as the “father of the iPod.”

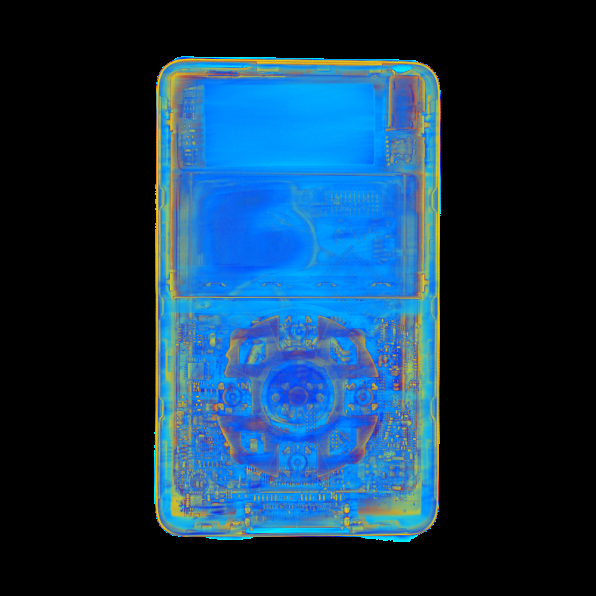

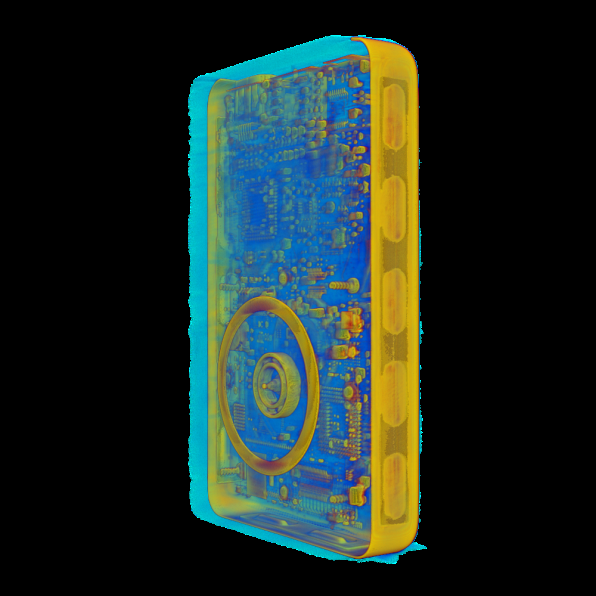

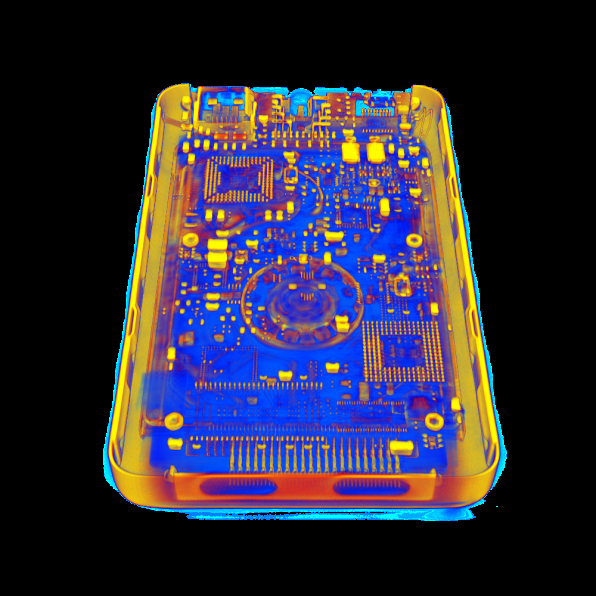

Consequently, looking at a picture of any particular iPod model’s innards reminds him of the design challenges it presented. “You go, ‘Oh, I remember we had to move this because of this reason, we had to move that, or we had noise issues,'” he says. “When you see those things, it just takes you back.”

The images that are sending Fadell’s mind reeling through time were created by Lumafield, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, startup that uses CT (computed tomography) scanning technology to peer inside an object, collect data about what’s in there, and then reconstruct it as a 3D digital image. Along with iPods, the company has scanned other, ahem, iconic items such as Lego minifigures, Nintendo Game Boys, Polaroid cameras, and Heinz ketchup bottles.

Lumafield began sharing imagery at its Scan of the Month site last November, long before the company left stealth mode in April. That’s because showing off the interiors of familiar products is just an entertaining, highly viral sideline. More important, the startup aims to democratize the use of CT scanning for quality-control purposes in product development and manufacturing—areas where it’s always had enormous potential but in many cases were cost-prohibitive.

“This technology’s been around for a long time, but typically these systems have cost a million dollars,” explains Lumafield cofounder and CEO Eduardo Torrealba. “We’ve done some pretty crazy engineering to bring the cost down to $36,000 a year.” Among the early adopters of the the company’s Neptune CT scanner and Voyager software: L’Oréal, Saucony, and Trek Bicycle.

Fadell’s interest in Lumafield is hardly an exercise in iPod nostalgia: He’s an investor in the company through his firm, Future Shape. “As soon as I saw [the scanner], I said, ‘How fast can I write a check?'” he says. “Because at the end of the day, visualizing and getting into the details of things made of atoms is very difficult, especially when you have to disassemble them and reassemble them every time.”

He adds: “Another reason why you need Lumafield is because we’re doing 3D stacking of chips—dies on top of dies on top of dies. We need to go and look deep, and it’s only going to become more complex.”

The fact that many gadgets are now water-resistant complicates matters even further: “As soon as you bust them open, you ruin the seals,” he says. “You can’t put them back together—it’s a onetime kind of design. And so to be able to look [inside] that and inspect it, that’s a superpower.”

Back when Fadell headed Apple’s iPod group, “we never had an X-ray machine,” he laments. He certainly could have used one, since Apple’s MP3 players were full of ambitious, sometimes risky feats of engineering. (Apple finally sprung for a CT scanner to help design the iPhone.)

When the original iPod was announced on October 23, 2001, its defining proposition compared to existing MP3 players was summed up in its soon-to-be-famous tagline: “1,000 songs in your pocket.” That selling point—a bit mind-boggling at the time—was made possible by the tiny 5 GB hard drive the iPod used for storage instead of a flash-memory chip capable of holding only an album or two.

The same consumers who treated their laptops gingerly were used to tossing existing portable music players such as the Sony Discman in a purse or letting them rattle around in a car. Apple wasn’t going to train them to do otherwise with an iPod. According to Fadell, Toshiba—the drive’s maker—thought that was a recipe for disaster. “When you have rotating media and you’re going to drop it, you don’t know what it’s going to do,” he says. “Toshiba was like, ‘You’re crazy—you’re never going to do a portable music player with this, the drive’s going to fail.'”

Apple went ahead with its plans, and transformed how people listened to music. But the company did know that hard drives’ bulk and fragility were drawbacks. From the start, it looked forward to the day when high-capacity flash storage would be affordable enough to build into an iPod. “We were always doing the competitive stuff and saying, ‘Oh, flash is growing up,'” Fadell says.

The first flash-based iPod was 2005’s iPod Shuffle, which was scarcely identifiable as a spin-off from the original iPod: It was the size of a pack of gum, had no screen, and could play music only in shuffle mode. The $99 entry-level model had space for only 120 songs.

However, eight months later, Apple replaced the hard-disk-equipped iPod Mini with the flash-based iPad Nano. Flash memory was still pricey enough that the $199 version held 512 songs, with a 1,000-song model available for $249. But the big news was that the highly capable Nano was tiny, and thinner than a No. 2 pencil—something that Apple could never have pulled off if there’d been a disk inside. It made for one of Steve Jobs’s most genuinely surprising keynotes.

When Fadell looks back at the Nano, the first engineering challenge he brings up is battery life. The device’s svelte dimensions necessitated “a much smaller battery than the big, full-size battery that was on the classic [iPod] or even on the Mini,” he says. The iPod team managed to wring enough life out of the Nano’s nano-battery to promise up to 14 hours of music playback, the same claim Apple made for the entry-level full-size iPod available at the time.

But once the player was in the hands of consumers, an anticipated problem emerged. Users tended to stick their tall, skinny iPad Nanos in their back pockets—and then sit on them. If the Nano flexed, that could damage the circuit boards inside. To confuse matters, pressing down on the click wheel sometimes applied enough pressure to get the board working again—temporarily.

We’d get all these weird, intermittent errors,” Fadell remembers. “If we could have looked inside with a machine like the Lumafield machine, we would have been able to diagnose it much more quickly.”

BEYOND THE IPOD

The first Nano might have been the iPod line’s high point as a tapestry for Apple’s imagination and engineering chops. And by the time it was released, work on the iPhone was well underway. Apple’s phone would be stuffed with technologies not present in iPods: a large multi-touch touchscreen, a cellular modem, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, cameras, and more.

Still, Fadell, who oversaw the iPhone’s hardware, says that all the expertise in miniaturized electronics the company gained from iPods was directly applicable to the iPhone project. After all, until the iPod came along, the smallest Apple computing devices were laptops—ones that were behemoths by 2022 standards.

“When we got there, Apple didn’t understand about 0402 resistors and capacitors—like, really small stuff,” Fadell says.

Even before the iPhone was a reality, Apple knew that an MP3 player with flash storage wasn’t the future of music. Internally, the company had been talking all along about a concept it called “the celestial jukebox”—music stored in the cloud and streamed to a pocketable gadget, as Pandora, Spotify, and Apple Music would eventually do. “We knew the next big thing after flash was all your music, no 1,000 songs or 10,000 songs,” Fadell says.

A

Though the iPod is now officially gone, it’s hardly forgotten. Lumafield CEO Torrealba says that the startup draws inspiration from the speed with which Fadell and his team brought the original model to market more than 20 years ago. Now that Lumafield has deconstructed iPods with its Neptune scanner, it plans to continue to use its technology to celebrate other classic technology.

“There are a lot of devices that people are really interested in,” Torrealba says. “Being able to highlight that really amazing engineering that goes into these hidden details is something that we want to be able to do with Scan of the Month, in perpetuity, as a company.”

As for Fadell, he refuses to think about the iPod in the past tense. “The Apple II brand doesn’t exist anymore, but it does—it’s a cornerstone of the company,” he argues. “The iPod is a cornerstone of the company. The iPhone would have never existed without the iPod. The iPod is never going away, no matter whether there’s a product named that or not.” The engineering that made it all possible is one big reason why.s all your music in your pocket became reality, iPods in their original form faded away. In 2014, Apple discontinued the iPod Classic, the last direct descendant of the 2001 full-size model. The final iterations of the Nano and Shuffle met the same fate three years later. And earlier this month, the company announced that it would end sales of the iPod Touch—more a phoneless iPhone than a music player, but still the last product to carry the iPod name.