“Countries with high levels of mask compliance did not perform better than those with low mask usage”; “Mask Mandates [are] Associated With Increased Covid Death Rate”

Inadequate support: Articles claiming that mask-wearing worsens COVID-19 and causes more deaths are based on two flawed ecological studies that don’t provide evidence supporting such claims. The articles also cherry-picked these two studies without considering the body of evidence that supports the use of masks to prevent infections and deaths.

Flawed reasoning: The two studies reporting that widespread mask usage led to higher COVID-19 mortality failed to account for variables other than mask-wearing that also influence the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, such as virus circulation and healthcare capacity in different regions.

Ecological studies look for relationships between an exposure (like mask-wearing) and an outcome (like COVID-19 cases) using aggregate data from whole populations. However, such studies are highly vulnerable to spurious correlations if researchers don’t account for confounding factors, which are variables that influence an outcome, independently of the variable being studied. Well-designed studies that account for confounding have reported that widespread mask-wearing reduces the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

FULL CLAIM: “Countries with high levels of mask compliance did not perform better than those with low mask usage”; “Mask Mandates [are] Associated With Increased Covid Death Rate”

Mask mandates in public spaces have been a common feature in most countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, as countries sought to limit the spread of the virus. But the proliferation of mask mandates was equally met with growing resistance promoted by misinformation, such as false claims that masks are harmful or ineffective at reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2, as Health Feedback documented in multiple reviews.

On 5 June 2022, Townhall Media published an article titled “Mask Mandates Associated With Increased Covid Death Rate”. Indeed, the Townhall article had been presaged by The National Pulse and the Counter Signal, both of which had published two articles in May 2022 making similar claims. These three articles together received more than 16,000 interactions on Facebook and Twitter and 7,000 shares on Facebook, according to the social media analytics tool CrowdTangle.

However, the articles are based on two studies that don’t provide evidence supporting their claims that mask-wearing worsens COVID-19 or causes more deaths. As we explain below, both studies have serious limitations and methodological flaws that call the reliability of their conclusions into question. The articles also cherry-picked these two studies while ignoring evidence from robust, better-conducted studies that contradicts these claims and indicates that widespread and consistent use of face masks reduces SARS-CoV-2 spread within the community and prevents deaths.

Finding a positive correlation between mask-wearing and mortality at the population level doesn’t imply that face masks are harmful; it is important to take into account other factors that also influence COVID-19 mortality

The first study was published in the journal Cureus in April 2022 by Beny Spira, a professor of microbiology at the University of Sāo Paulo. Spira used data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington to correlate mask-wearing with the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths per million people in 35 European countries from October 2020 to March 2021.

Spira found no overall correlation between mask usage and the rate of COVID-19 cases and deaths, leading him to conclude that face masks were ineffective at reducing SARS-CoV-2 spread. He did find a “moderate positive correlation between mask usage and [COVID-19] deaths in Western Europe”, which he interpreted as evidence that “the universal use of masks may have had harmful unintended consequences”.

The second study, published in Medicine in February 2022, is authored by Zacharias Foegen, who didn’t list any affiliation to a university or research center. This study evaluated the effect of mask mandates on COVID-19 fatality rates in the U.S. state of Kansas—which allowed each county to implement or opt out of mask mandates—between August and October 2020.

Foegen concluded that mask mandates caused about 50% more deaths in the counties that implemented their use compared to those that didn’t. He further hypothesized that face masks caused more severe COVID-19 through a mechanism that he called “the Foegen effect”, by which “breathing in one’s own virions” causes them to spread “deeper into the respiratory tract”. But he offered no evidence demonstrating the existence or even the plausibility of this mechanism. Indeed, Foegen conceded that such an effect has never been demonstrated in the scientific literature for any disease. So at this stage, this is a purely speculative supposition.

More importantly, Spira and Foegen’s analyses are fundamentally flawed and don’t support their own conclusions. Both analyses used aggregated data at the population level to establish correlations between different variables, which is known as ecological studies.

One of the most significant limitations of these studies is that they don’t have data at the individual level. For example, not everyone wears masks, and those who do may not wear them most of the time. In order to know whether there is a basis for attributing changes in infections or deaths to the use of face masks, we need to compare the number of cases and deaths among mask-wearers and non mask-wearers. Put simply, these studies can’t tell us whether COVID-19 deaths were predominantly among people who wore face masks. In their current form, the studies aren’t equipped to tell us whether there is a causal relationship between mask-wearing and a higher risk of death from COVID-19. The failure to recognize this limitation is known as the ecological fallacy.

Furthermore, Foegen evaluated the effect of face masks assuming that mask usage was higher in counties that implemented mask mandates compared to those that didn’t. However, this assumption is not always correct because the level of mask usage within a community depends on other factors such as mask acceptance and risk perception. While there is some evidence that mask mandates increase mask usage within a community[1], they don’t necessarily imply that mask usage in that community is higher than in other regions without mask mandates.

As Health Feedback explained in earlier reviews, ecological studies are also particularly prone to bias due to confounding factors, which are variables other than the one measured—in this case, the effect of face masks—that directly affect the outcome (COVID-19 cases and deaths). For example, variables such as the level of virus circulation, new virus variants, control measures apart from face masks, and differences in healthcare capacity between countries or regions can also directly impact the number of infections and COVID-19 deaths. Failing to account for the effect of these variables can create spurious correlations.

These limitations might result in an apparent correlation or a lack of correlation that could be misleading. Spira didn’t even try to account for confounders and simply stated that “no cause-effect conclusions could be inferred from this observational analysis”. While Foegen claimed to account for infection rate, his methods for doing so are unclear. The same applies to the counties’ inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Because of these limitations, Spira and Foegen’s analyses don’t allow us to draw reliable conclusions about the effect of face masks on COVID-19 cases and deaths. Furthermore, data from better-quality ecological studies evaluating the effect of face masks directly contradict Spira’s and Foegen’s results.

For example, one large study published by Leech et al. in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) in May 2022 used the same mask-wearing dataset as Spira to evaluate the effect of face masks on SARS-CoV-2 transmission throughout 92 regions in six countries[2]. Mask-wearing data in this study, like the IHME data that Spira used, comes from the COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey, conducted by Mellon University and the University of Maryland in partnership with Meta. This survey collects reports from randomly selected Facebook users on variables such as COVID-19 symptoms, testing, preventive behaviors like mask-wearing and vaccination, and others.

Unlike Spira, Leech and colleagues did control for confounding factors, including time spent in public spaces, mobility, and non-pharmaceutical interventions other than mask-wearing, such as bans on large gatherings. The authors found that widespread mask-wearing was associated with an average 19% reduction in the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

One study published in 2020 evaluated the effect of maks mandates in Kansas counties between June and August 2020[3]. Counties that ultimately implemented mask mandates had higher initial infection rates compared to counties that didn’t. To control for this potential bias, the authors used trends rather than infection rates as an outcome measure. They found that mask mandates mitigated SARS-CoV-2 transmission in counties that implemented them and reversed the increasing trend in infections, whereas counties that didn’t issue mask mandates continued to experience daily increases in COVID-19 cases.

A more recent study published in JAMA also analyzed the effect of mask mandates in Kansas counties between July and December 2020[4]. This study controlled for variables such as additional restrictions, the date when mask mandates started, the number of days since the first recorded case, and the lag time between infection and hospitalization and deaths. The study showed that counties that adopted mask mandates had significantly lower rates of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths compared to those that didn’t.

Face masks limit the release of infectious respiratory particles from infected individuals and protect the wearer from exposure

SARS-CoV-2 is primarily transmitted through respiratory liquid particles carrying the virus, as Health Feedback explained in this earlier review. The risk of infection is determined by how much a person is exposed to these infectious particles. This, in turn, depends on the environment—such as whether it is outdoors or indoors, the level of ventilation—the distance to an infected person, and the amount of exposure time.

Face masks physically minimize exposure to infectious particles by reducing the release of such particles from infected individuals into the air (source control) and protecting the wearer from inhaling them[5]. Laboratory research shows that wearing a face mask reduces the amount of particles that a person expels into the air when speaking or coughing and halves the distance that these particles can travel[6,7].

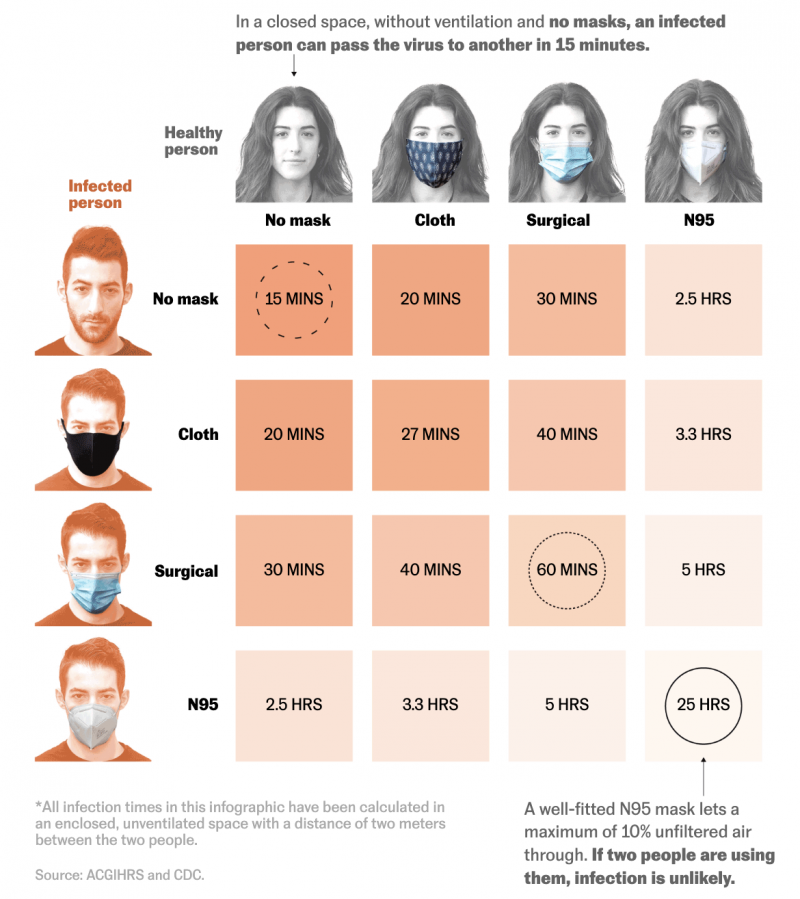

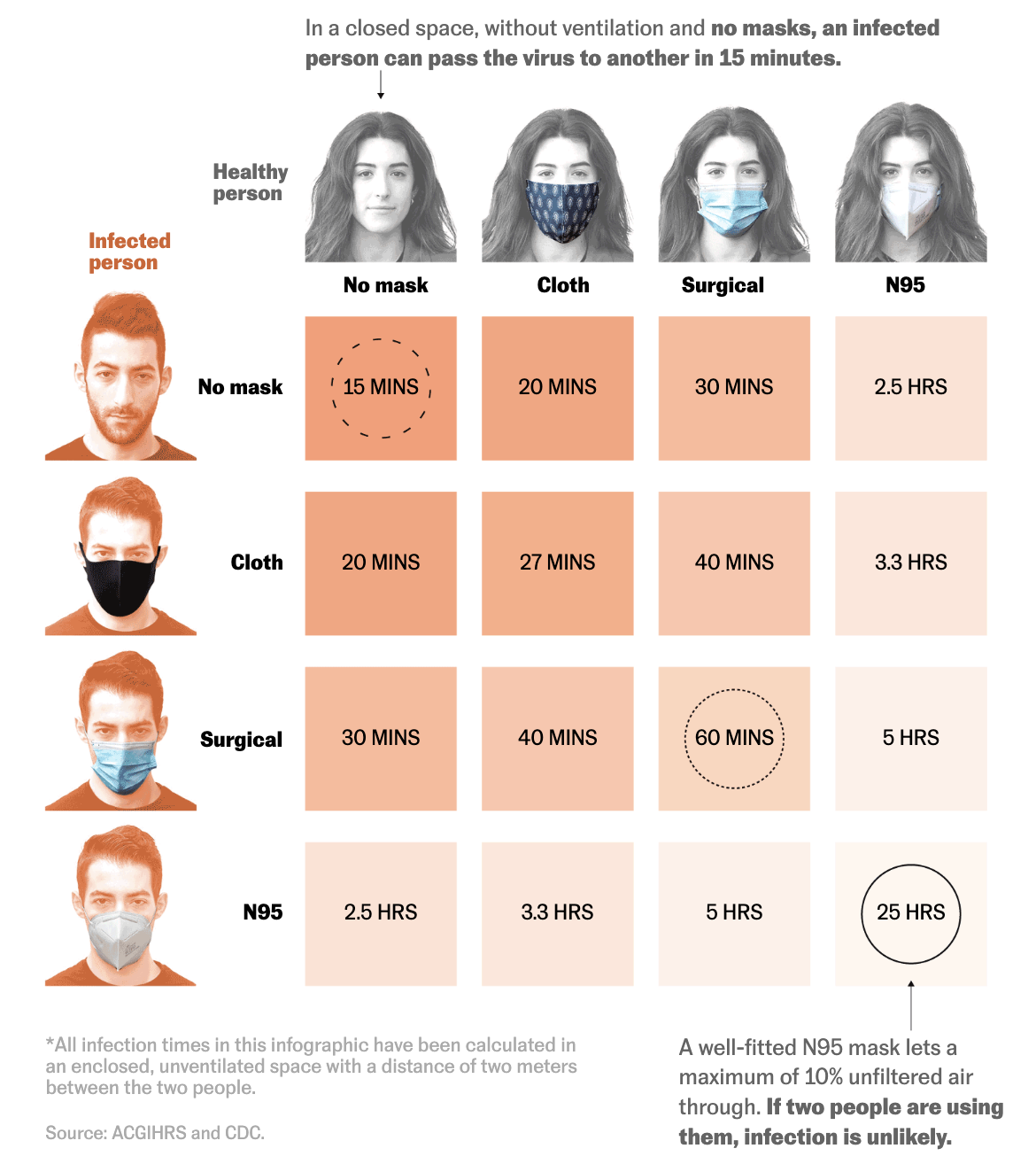

To illustrate the protection offered by face masks, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists estimated the time it would take to become infected if exposed to an infected person (time to an infectious dose) with or without wearing face masks. The baseline is based on the CDC’s definition of close contact, which occurs when someone is less than six feet (1.8 meters) away from an infected person for at least 15 minutes. According to the estimates, the time for infection would increase from 15 minutes when no one wears a face mask to 25 hours when both persons wear a well-fitted N95 mask (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Estimated time for infection depending on the type of face mask a person is using. Timeframes were calculated in an enclosed, unventilated space with a distance of two meters between an infected and an uninfected person. Image source: El País.

High-quality studies indicate that widespread mask-wearing reduces community transmission in the real world

Much of the controversy about the use of face masks as a measure to limit the spread of COVID-19 was fueled by the lack of data at the initial stages of the pandemic. While evidence indicated that surgical masks and N95 masks effectively reduced the spread of respiratory infections in healthcare settings[8], data about their impact on community transmission were scarce and conflicting. However, that isn’t the case anymore.

Several robust studies now indicate that face masks effectively reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, COVID-19 cases, and deaths in the real world, particularly when combined with other measures such as physical distancing and frequent handwashing[9,10].

In December 2021, Abaluck et al. published in Science the first randomized controlled trial—the gold standard to evaluate the efficacy of a new intervention—studying the effect of face masks on community transmission in nearly 350,000 people from 600 villages in rural Bangladesh, India[11]. The researchers distributed free masks and promoted their use in 200 villages and then analyzed mask-wearing and symptomatic infections in these villages for the following two months compared to the villages with no intervention (control group).

In villages where the intervention was applied, mask-wearing increased to 42.3%, compared to an average of 13.3% in villages with no intervention. More widespread use of masks translated into 10% fewer symptomatic COVID-19 cases, with surgical masks showing a greater reduction (11%) than cloth masks (5%). However, one caveat is that the study didn’t test people without symptoms, so we don’t know whether mask-wearing could have further reduced transmission from asymptomatic people.

A 10% reduction in COVID-19 cases might not seem like a substantial effect. However, it’s important to note that the intervention only increased mask wearing from 13.3 to 42.3%, resulting in less than half of the people wearing a mask. The fact that the researchers were still able to observe a beneficial effect with only a modest increase in mask-wearing suggests that universal masking might be highly effective in reducing SARS-CoV-2 spread. Finally, the intervention reduced symptomatic infections in people over 60 by 35% compared to the control villages, indicating that face masks were particularly effective at protecting vulnerable people.

Another study published in February 2022 analyzed the impact of self-reported use of face masks in public indoor settings in nine multi-county regions in California from February to December 2021[12]. The study evaluated different types of masks, including N95 masks, surgical masks, and cloth masks, and the effect of consistency in mask-wearing (wearing a mask all, most, some, or none of the time). The study found that people who consistently wore a face mask in public spaces were around 50% less likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2. Although the consistent use of any face mask reduced the likelihood of infection, N95 masks offered the highest degree of protection, followed by surgical masks.

Conclusion

Articles by Townhall Media, the National Pulse, and the Counter Signal from May and June 2022 claiming that using face masks causes more infections or COVID-19 deaths are based on two methodologically flawed studies that don’t provide evidence supporting such claims. In contrast, large and robust studies conducted over the past two years demonstrate that face masks effectively reduce the spread of respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 in community settings.

Although N95 masks offer the best protection against infection, consistent use of any well-fitted mask in public spaces helps reduce the spread of respiratory infections like SARS-CoV-2 within the community. This is particularly true when compliance is high and when mask-wearing is combined with other measures such as physical distancing and frequent handwashing.