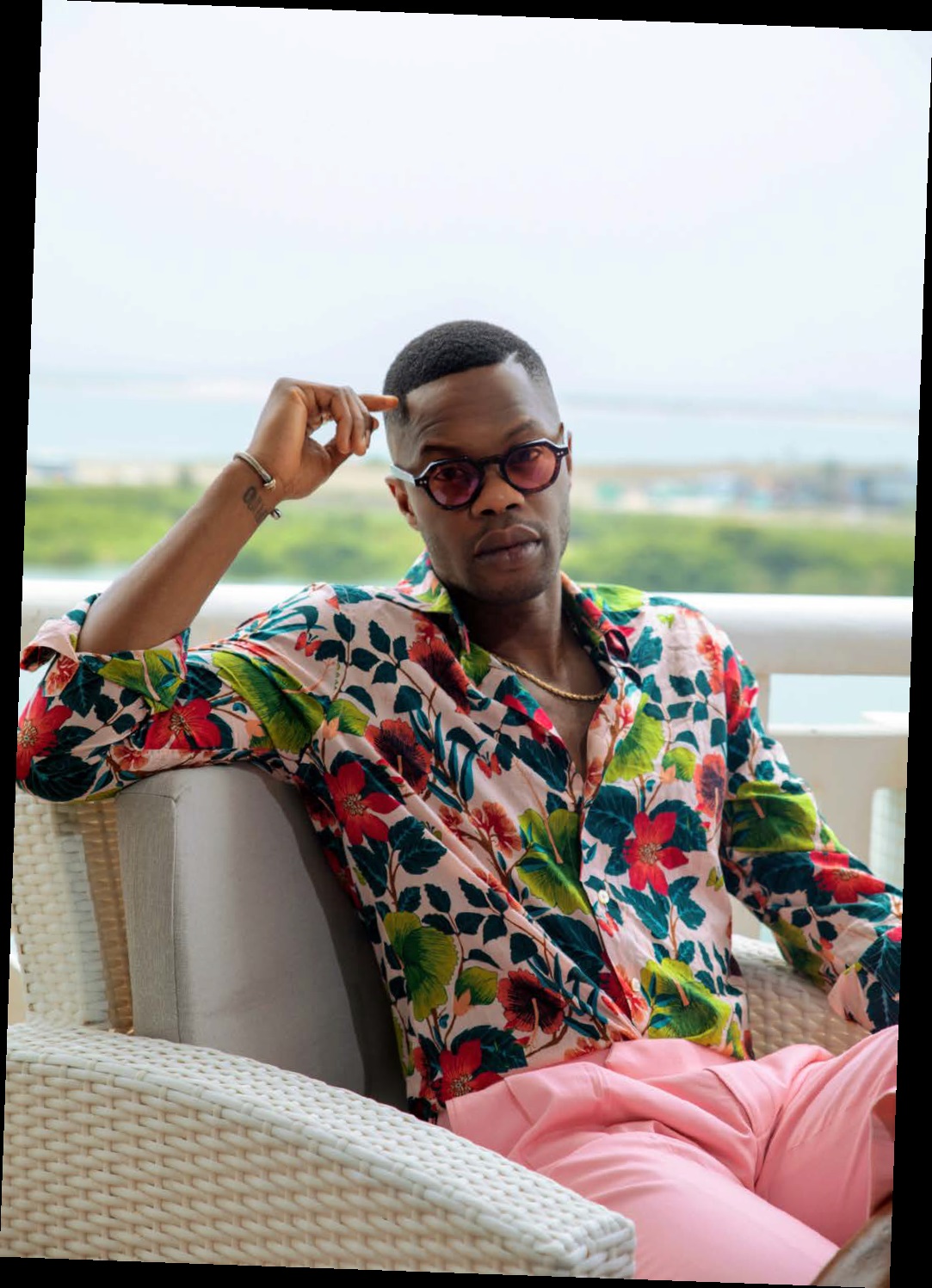

COVER Bringing Hollywood Home: Sam Adegoke Onah Nwachukwu January 1, 2023 “Awon omo Blake ti wan ti sonu, ika owo mi bayii lowa,” (which translates to ‘I have Blake’s little lost children in the palm of my hand’) a fictional character, Jeff Colby, acted by Nigerian actor, Sam Adegoke, tells his dad, played by fellow Nigerian actor, Hakeem Kae-Kazim, in a scene of America’s hit TV series, Dynasty. When this particular episode aired, it was the most discussed thing on Twitter—an actual Yoruba man was speaking the original Yoruba language on American TV. Nigerians were visibly thrilled by the representation. Arts have always been the vehicle that fosters cultural intertwining. We have recently seen that vehicle oiled up to allow a more significant cultural shift that has since placed a positive spotlight on Nigeria and its people.

But before afrobeats began its push for mainstream acceptance and the partnerships that help export our talents abroad were formed, one man didn’t hesitate to represent Nigeria on the biggest stage, Sam Adegoke. When Sam, who was already cast to be in the series, Dynasty, pitched to the showrunner, Sally Patrick, to make his character and his family hail from the most populous black nation in the world, it was a novel idea that would end up thrusting him into the limelight, quickly turning him into fans favourite, not only in the United States where the show was made but also back home in Nigeria. DOWNTOWN’s Editor, Onah Nwachukwu, chats with the actor about his upbringing, which was split between both countries affording him dual citizenship, navigating America as a young black man from a strict missionary household that had TV banned, and eventually ending up in Hollywood as one of the country’s biggest exports on TV.

Related article - SONY MUSIC PUBLISHING LAUNCHES INAUGURAL WEST AFRICA SONGWRITER CAMP

What was it like living in America as a Nigerian child?

Were there any rules and guidelines that your parents instilled in you that were Nigerian culture? Yes, absolutely. Excellence in everything. There was no room for anything else. My parents come from rural Ibadan, and my father’s family were farmers. And then, he got a very junior-level position working for the US Embassy in Nigeria. And that’s how we were able to get dual citizenship. So coming from that type of rural background, you can imagine we get to America, the Promised Land, and it’s the same story that any immigrant Nigerian or African family deals with. It is academics, and if you’re not in school studying, you’re at home studying. If you’re not at home studying, you’re praying in church. And if you’re not in church praying, you’re working. So those are the four things you could do. Back then, it felt very rigid and regimented to me; very shackling, and I hated it. There was a certain level of freedom that I did not feel growing up in that environment, coupled with the fact that my parents were ministers in this church— Deeper Life, and launched a church in St. Paul, Minnesota, where I grew up. When you’re young, you don’t see the value of that. As you age, those things stay with you. I’m grateful for the incredible opportunity to do what I love to make a living. And I recognise that’s not afforded to all, so that same discipline instilled in me with academics and relationship with God, etcetera, is the same thing that I apply to my work. Because I know it’s rare to have this, I want to make the most of it.

How did you decide you would be an actor for a child brought up by parents who are ministers at Deeper Life church?

They don’t watch television(TV). It’s so funny you said ‘no TV’ because my brother James bought this small black and white box TV, and we would hide it in the closet and bring it out sometimes to watch shows like Martin, Fresh Prince, you know, all those shows that were like popping in the 90s. The funny thing is—life is so interesting—the same people, my parents, who weren’t encouraging of the arts (because they want you to become, as they say, a doctor, lawyer, engineer or a disappointment, right? Those were my options), are the same reason I went into acting. My mom is an amazing storyteller, she was the first person who ever told me stories, and she tells these strange Nigerian proverbs, you know, ‘if you kill a goat, you will die,’ you know those kinds of stories, and I’m sitting like, ‘what the hell does this mean? Can I just go back outside and play now?’ So I always grew up with this love of storytelling, and we’re just natural storytellers by virtue of our culture. And then, in our church, we did faith-based plays, David and Goliath, The Resurrection, The Birth, The Death. My brother would often write the plays— I’m the youngest of seven, so we all have to have something we do in the church. My sister would also co-write with him. And then they would direct the plays, we were all like 8, 9, 10, dressed up in your long white kaftan holding your staff, and playing Moses or something, and I just enjoyed it. I think that, and my mother’s storytelling was what sowed the seed of ‘this could be something that you could potentially do for a living.’ But I didn’t do it till much, much later, just because of fear. So you pursue what you think you need to pursue based on that idea of, you’re here, in this country, so you have to make the most of it. There’s no time for anything frivolous, no time for the arts; you have to earn income and support your family, which I did for many years. I didn’t get around to pursuing acting until many years later. I’m grateful that I did that. That moment finally happened, and I was like, ‘listen, ayeopemeji, (life doesn’t come around twice). So you can have a good income, I made good money working in corporate, you can travel and do all these things, but if it’s not fulfilling, then you’re just earning a living; you’re not actually living.

What was your parents’ reaction to you deciding that you wanted to act for a living?

They almost crucified me. I studied Marketing and Finance at Business School. I worked in consumer insights and human resources, and the company I worked with—General Mills, moved me to LA (Los Angeles). The crazy thing is I have a very artistic family. I have two brothers who can sit here and draw you; it will blow your mind. My sister sings and plays the piano in the church. I played the bass guitar in the church, and my brother Michael drummed. I always tell people we are like an African Jackson Five, but we did praise and worship in the church. Funnily enough, I enrolled in a theatre arts program during my freshman year, but my eldest brother said, ‘No, not in this house. Don’t study that. Study business or marketing. That’s what’s acceptable in this house.’ And I worship my older brothers because they raised me when my parents were busy working in the church. I did. I did it for many years. And then, I finally just said, ‘No, this, this isn’t really me.’ So I cashed up my 401k, quit and went to the Academy of Art in San Francisco. They have an art program there. And I didn’t even tell anyone. I studied menswear in theatre because my uncle was a tailor in Nigeria, and I always liked to play around with clothes. People knew I was doing that but didn’t know I was doing the theatre because it’s still like, you’re going to move to LA and become an actor; it just sounded cliche, sounded stupid. And I’m grateful I didn’t tell anyone because they say, ‘A prophet is not without honour save in his own country’, right? It’s usually those closest to you because they already know you in one light, and there’ll be the biggest voices of dissent towards your dreams, and they do it unknowingly. I would do the same if my brother showed up tomorrow and said he wants to be like a jazz musician. I would laugh like okay, you’re an engineer; that’s how your mind works. I wouldn’t say it out, but I would think it in my head. So I just kept doing it.

What do you love about acting?

Contrary to my character on Dynasty and that show’s tone, acting is therapy for me. I mean, I jazz it up and make it sound sexy, but I remember, funny enough, my older brother, John, was the first one to start taking acting classes in LA. I was doing some runway stuff, dabbling around entertainment, and he invited me to the class he was taking in LA, in a studio theatre— Ivana Chubbuck’s class, to sit in on it. He’s like, ‘listen. I think there’s something here. I think you could do this. I’ve been doing this class for about four or five months.’ So I sat in on the class and watched my brother perform a scene with another scene partner. And I was like, ‘Who the hell?’ I didn’t know who this guy was. It was a deeply emotional scene, coming from a guy who was a part of a family of six very macho boys, so you can imagine my surprise. I had never seen this emotional side of my brother, and afterwards, I was like, ‘John, what the hell was that?’ And he didn’t have the language to articulate his experience. So I jumped into it and realised, ‘Oh, wow, this is therapy.’ There are some things we need to deal with— being Nigerian men, particularly, that we can embody within a character through which you kind of exercise these things. It’s not Sam crying and being moist; it’s the character. But you don’t realise you’re releasing stuff through that. And that became like a drug for me. I was like, ‘Okay, I’m learning more about myself outside of the professional side of Sam, the athlete outside of Sam, the man or whatever idea man is supposed to be. You’re discovering that for yourself. And that’s what I love most about it. It’s become therapy for me. It led me to do therapy myself with a formal therapist, which was a hilarious concept to me growing up. when I was younger, I thought, ‘why are you gonna pay a complete stranger to tell you about yourself?’ Like, ‘give me your money, and I’ll tell you everything about yourself.’ Now, I tell my brothers, ‘all you negroes need therapy. You guys need some things you got to work through.’ So it’s just beautiful, it’s being a child again, it’s make-believing, pretending and to do that for a living? God is good.

Have your parents come to terms with it?

I still don’t know if my parents know what the hell I do (laughingly)— just kidding. I mean, they do. Now it’s like, ‘My son; he’s on Dynasty doing his thing. Have you seen him? God is good.’ But my parents are so spiritual, there were certain times I made the mistake of watching an episode with my mom, and I didn’t want her to see it. It was an episode where Jeff and Fallon finally fornicate. It’s a really heavy scene, and my mum says, ‘See my son, see my son on TV, just baring your chest like a male prostitute for everyone to see. Is this what you’re doing? Is this how I raised you?’ And then the episode ended, and she was like, ‘Okay, so when is the next one?’ I had her hooked, and then she watched the whole series and had so many questions. So they finally came around, but it was undoubtedly a long journey, and it continues to be. But my mom knows I’m writing now because I want to write and develop stories out of Nigeria on a global scale. Great stories like the story of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Delta people, the Ogoni people, and Dele Giwa— our heroes. They’ve made the Martin Luther Kings and Malcolm Xs in America, so I want to bring these stories to a global front. And she consistently asked about that. So she supports me now.