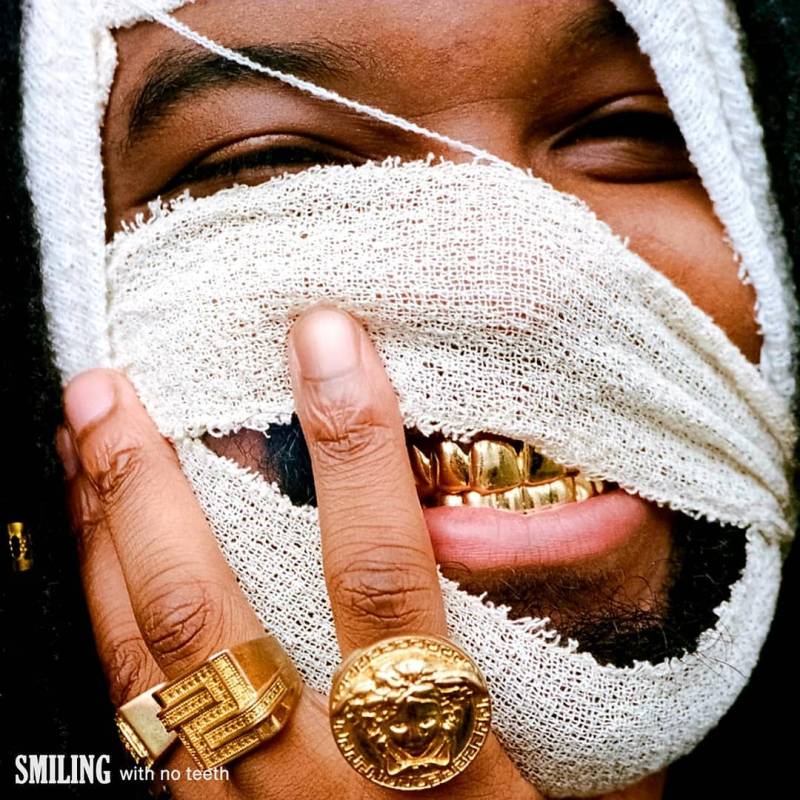

“I’m very happy in this place. I feel at home,” Naira Marley, grinning ear to ear, tells me from his dodgy Zoom line in Lagos, Nigeria. For the 31-year-old singer, songwriter and rapper, making the move from the South-East London borough of Peckham (or ‘Pecknarm’, as it was once known, due to its Vietnam war-like street violence) was the best thing for him and, ultimately, his career. “In the UK, problems are always around the corner,” he adds, “but here, I’m not involved with any of that gang stuff—just good living.”

Born and raised in Nigeria’s Lagos State, at the age of 11, Naira—real name Azeez Fashola—moved to England with his family and settled in the heavily African-populated area of Peckham, but at school, he had some trouble fitting in. “I was always happy to be ‘fresh,’” he says on being seen as “fresh off the boat” to pupils, which had historically been used as a diss to first-gen immigrants. “When I was in school, I didn’t understand how some Black people would say they’re not African, like the Jamaicans and other Caribbean people. Even some African people pretended they weren’t African because it wasn’t cool to be that. I had to really fight my way through, but then it got to a point where I realised: “I am cool!” But the trolling from white kids, the trolling from Caribbean kids—it was a lot.”

Naira Marley (his alias a nod to the currency of Nigeria and one of his music idols, Bob Marley) would soon become the talk of the town when he dropped his debut single, “Marry Juana”, in 2014. This track, featuring fellow rapper Max Twigz, was one of the early iterations of a sound we know today as ‘Afroswing’, a blend of Afrobeats, road rap, dancehall and grime. A pioneer of the movement, which would later see chart hits by the likes of Kojo Funds, J Hus, and Not3s, Naira continued to bless his ‘Marlians’ (the name he gave his cult-like fanbase) with more and more underground hits, some of which were taken down by the authorities early on, before he started going back home and getting back to his roots. Today, now a full-time resident of Nigeria, Naira’s music is a far cry from his UK street-inspired output of the mid-2010s: this is Afrobeats through and through, his Yoruba tongue and traditional instrumentation used to great effect.

We caught up with Naira Marley to discuss his recently released debut album, God’s Timing’s The Best, life in Lagos compared to London, missing his children, Afroswing’s future, and more.

“Listen to the album and you’ll hear the proper Afrobeats sound. Not people singing R&B with African accents calling it Afrobeats.”

COMPLEX: You’re one of the pioneers of Afroswing; there’s no debating that. But your new project, your debut album—God’s Timing’s The Best—is much more traditional-sounding. What was the thinking process behind the way you wanted to approach this album and the way you wanted it to sound?

Naira Marley: I was trying to make it more global-sounding, so I linked up with a lot of other artists to make it have that feel while still sticking with my original sound: the Afrobeats sound. My fans have really taken to it—they love this version of Naira. They’re supportive and tell me that they’re proud of me for making that big move back home to Lagos and back to that original African sound. When I meet the fans now, they say, “I can’t believe you went from Lagos to England and then you moved back and took over.” So I’m proud of myself, too.

As you should be. For those who haven’t yet managed to take in the album, how would you describe it?

Listen to the album and you’ll hear the proper Afrobeats sound. Not people singing R&B with African accents calling it Afrobeats [laughs]. You get to dance! It’s just Naira Marley—good music from A to Z. I’ve put in the work with this project and I think that comes over in every song.

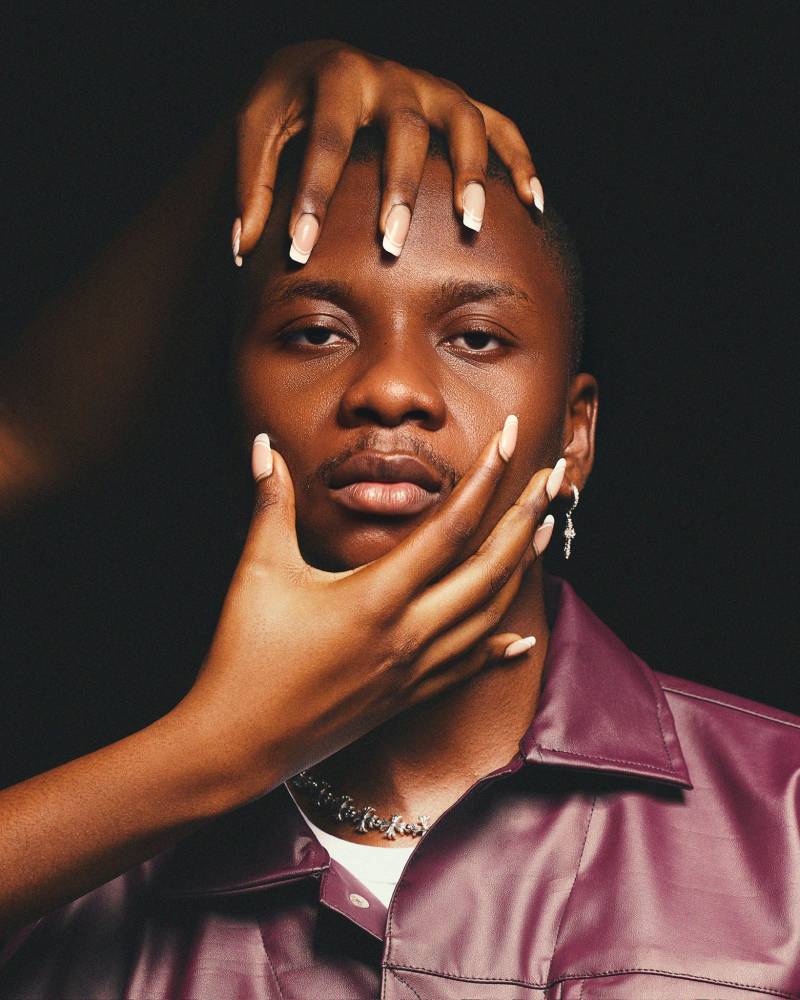

Personally, I think “O’dun”—a standout on the album —should be a lot bigger than it is. It has the potential to break through on a global scale like Wizkid and Tems’ “Essence” and Burna Boy’s “Last Last”. Do you agree, or is there another album cut that you think has the potential to cut through more?

It has the potential, definitely. I agree with you. I think it’s got the potential to really go international. I got Zinoleesky on the tune and he’s one of the biggest in Nigeria right now, but there’s still time for people to catch on to it.

Do you see yourself ever going back to making Afroswing and rapping on tracks more?

Of course! I have a song coming out and that’s gonna shake the room. It’s got a lot of influence from my earlier UK sound, so I’ll be back on that and I’ll be making some trap music every now and then too.

I’ve known about you since 2014, when you dropped “Marry Juana” on Rap City TV. That came out at the height of road rap, and that genre’s influence is definitely present in the track—even in terms of the lyrical content. How much of an impact did moving from Nigeria to Peckham have on the way you saw the world back then, and still see it now?

English wasn’t my first language back then, so now I’m just trying something in my first language—which is Yoruba. Now it’s just more of the culture, more Afrobeats. That was Afroswing and now it’s the proper Afrobeats. When I first got to the UK, there wasn’t much African music making an impact, so we had to fight for all of that and it was really hard work. I came to Peckham directly, which is, like, very dangerous with all the active gangs. That really affected my music. My music, at the time, was really violent because that’s what I was around.

But that made me who I am today. It opened my eyes to different aspects and it made me less naive to certain things. Living in England, I got to know about a lot of other countries and their cultures as well: Portuguese, Ghanaian, French, and so on. I picked up on things, certain slang, that I still use today and that’s all a part of what makes me, me. And then, obviously, I was obviously locked into Giggs, Skepta, and all the Fuji, highlife and traditional music from back home. But yeah, the UK helped my music a lot.

“I think I have enough money now to promote myself and do my own videos. I just need to know what a label could do for me that I can’t do for myself? It’s not really clear.”