Some portraits offer snapshots of their era – faces frozen in time and place, petrified in their perishability. A rare few feel torn from eternity. Rembrandt could do it. Set against smoldering gloom, his serial selfies seem less a ledger of his slipping flesh than a glimpse into another realm – an elsewhere unlocked by the insertion of disjointed details that detach his countenance from its transitory nowness: a flouncy frock from a bygone century; an anachronistic hat; a plume plucked from antiquity.

Endangered but not extinct, that visionary flair has survived to our own age in the canvases of British artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, whose arresting portraits, if portraits they might be called, are the subject of a major mid-career survey at Tate Britain enticingly entitled Fly in League with the Night (an exhibition whose initial run in December 2020 was cut short because of the pandemic). One might be surprised to discover that the 17th-Century Dutch Golden Age master is birds of a feather with a 21st-Century black female artist of Ghanaian descent. But the soul selects its own society, and genius has its own genealogy. Consider, for instance, Yiadom-Boakye's painting A Passion Like No Other, a misty mirage of a mysterious young man – half in shadow, half in deeper shadow – that the London-born artist created in 2012, the year before she was shortlisted for the prestigious Turner Prize.

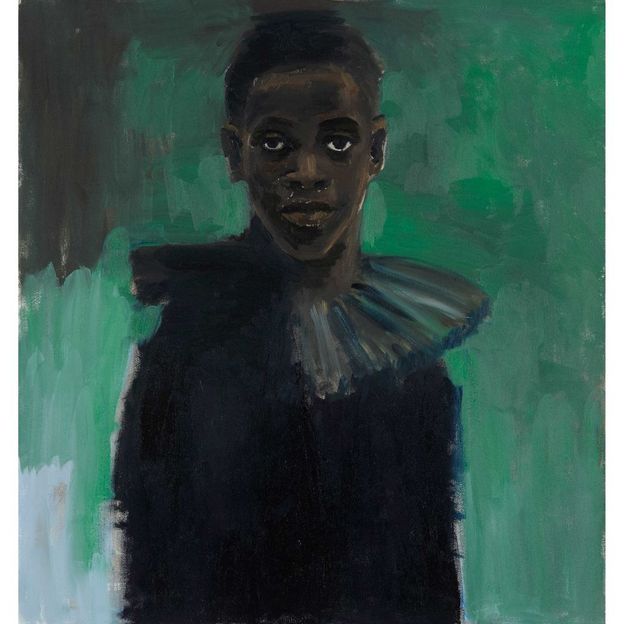

Clad in inky black clothes, with a flamboyant, feathery ruff radiating iridescently from his neck, the transfixing figure is silhouetted by a green gloam that shudders behind him. Soulmate of Rembrandt's smoky simulacra, he seems to have flown to us, not from another time or place, but from no time and no place. His is a vaporous otherwhere that looms outside of history and beyond geography. And yet the weight of his interloping presence in the here and now – the heft of his obsidian eyes – is irrefutable and anchors the suspended moment, as if our very existence depends on his. Either we are dreaming of him or he is dreaming of us.

Blink and they might disappear, dissolve into darkness – fly in league with the night

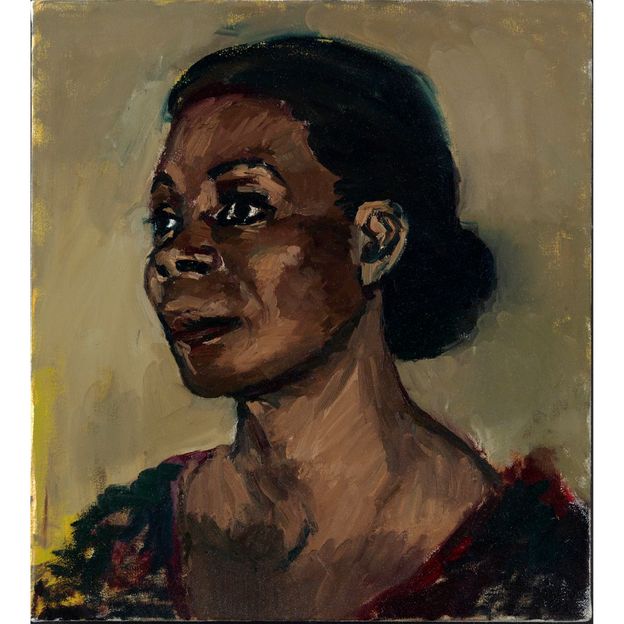

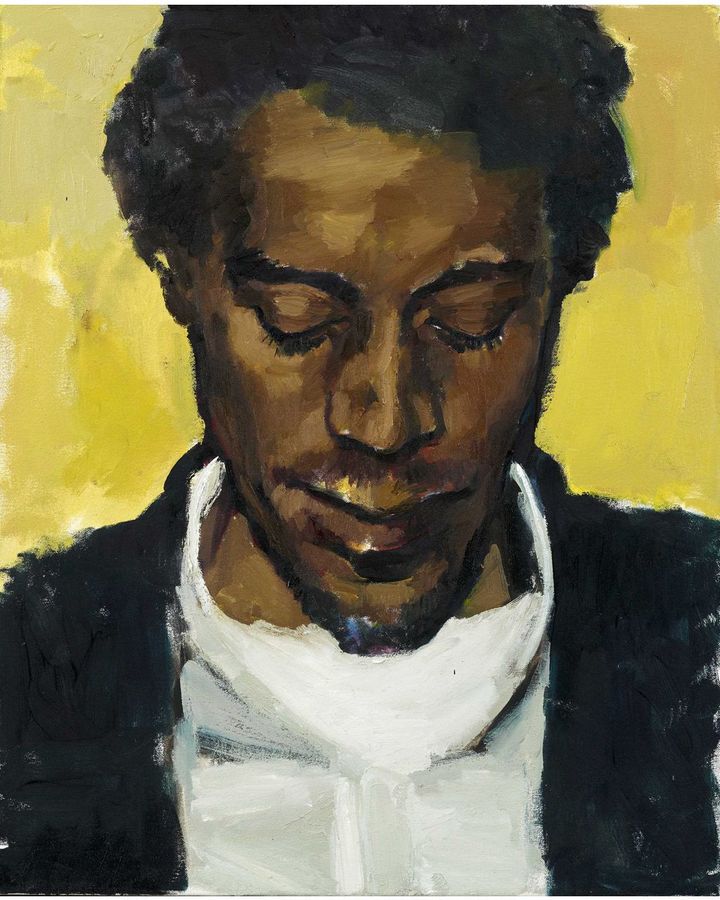

A Passion Like No Other is emblematic of Yiadom-Boakye's enigmatic magic – of her ability to conjure on canvas an uncanniness of spirit – a "presence that disturbs", to invoke a phrase from the Romantic poet William Wordsworth – whose depth of character is as indisputable as its depiction is evanescent. What makes Yiadom-Boakye's subjects so emphatically affecting is that their attachment to the world they inhabit, not unlike our attachment to ours, is tenebrously tenuous. Blink and they might disappear, dissolve into darkness – fly in league with the night. In fact, they were never here in the first place. However alluring we may find the aura of the personas presented in paintings such as The Cream and The Taste (2013) or Citrine By The Ounce (2014), luminous meditations on meditation, they have no actual correspondence to real people who live or have ever lived in our world. A supreme fiction wrought in the foundry of the artist's mind, they are mere pigments of the artist's imagination.

"Lynette creates the characters that populate her paintings like a writer builds a character in a novel," Tate's director of exhibitions, Andrea Schlieker, tells BBC Culture. "They're invented characters. And she gives them a space in her paintings that is quite unusual in that it is so timeless. She avoids anything in the clothing, in accessories, in the interiors or exteriors they inhabit, that relates or that could associate the particular portrait with a particular period. So I think that the timelessness that she very, very deliberately creates aids the exploration of the inner life. Everything is really guided for the viewer to this exploration of the inner life. The states of the soul, the sort of deep humanity that is expressed by each of these figures, which seem so real. It is hard, I think, for viewers to believe that they are all invented."

A painter of the invisible

Born in London in 1977 to parents who had emigrated in the 1960s from Ghana, not long after the former British colony had gained its independence in 1957, Yiadom-Boakye has spent the past two decades mapping the inner lives of her poetic constructs. Consisting of some 70 oil paintings and charcoal drawings created by the artist since 2003, when she graduated with an MA from the Royal Academy Schools, the exhibition invites visitors into an imaginary world that is at once profoundly familiar and unsettlingly strange. We recognise the mute language of furtive glances and latent gestures with which the characters in her narratives communicate with each other – in works such as Pale for the Rapture (2016), a diptych of deep introversion – from our own secret lexicon of unspoken expressions that we thought no one had ever noticed.

But Yiadom-Boakye notices everything. "She constructs her characters from scrapbooks that she has accumulated over the years," explains Schlieker. "These visual ledgers of obsessive observation, we're told, are filled with photographs of friends and family but also postcards of famous paintings she admires, or something ripped out of a magazine – a glance, a light, a gesture. All of this is fed into the creation of these extraordinary characters, this extraordinary mystery." It is tempting to infer from Schlieker's evocative description – "a glance, a light, a gesture" – that the imagination of the artist is most attentively attuned to the French Impressionists' fascination with the fleeting. In truth, the teasing texture of her riddling narratives aligns them more closely with the indecipherable shadows of Walter Sickert, say, or John Singer Sargent – sources the artist herself has cited. Light and colour in Yiadom-Boakye's work is rarely the subject itself, and more often an inscrutable dimension of her subject's consciousness. "She constructs these narratives that are for us to unravel and they are all so mysterious," says Schlieker. "At first glance, you look at the painting and you think 'oh yeah, I recognise this; it's a portrait of somebody unknown to me'. But the more you look at it, the more mysterious it becomes, especially with the very few carefully inserted details."

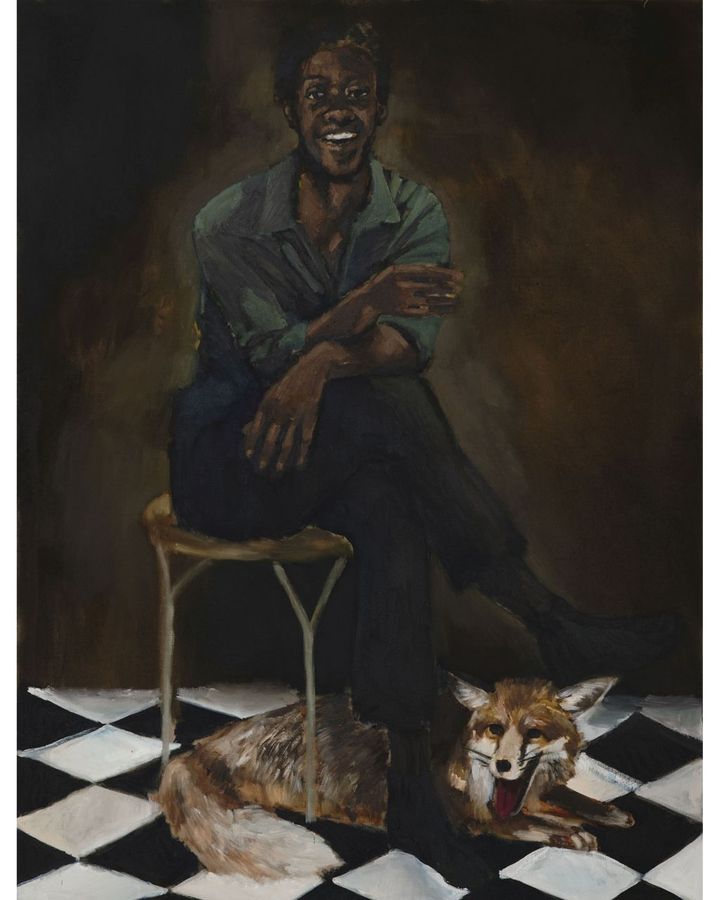

Yes, the details. Though Yiadom-Boakye's paintings may seem ruthlessly stripped of ephemeral particularities, whittled to poignancy and a rawness of intimate vibe, frequently she interrupts the sprawling spareness with an intriguing prop, on loan from elsewhere, that complicates our reading. That frilly ruff, for instance, in A Passion Like No Other – a carnivalesque flourish that calls to mind an outmoded accessory of the 16th Century or the comedic costume of a pantomime Pierrot. Once spotted, these curious accouterments are everywhere, and often take the animated shape of displaced animals: a guffawing fox at the foot of the smiling figure in Black Allegiance to the Cunning (2018), the lemony passerine that perches on the finger of a bespectacled man in All Manner of Comforts (2016), or the piqued owl contemplating prey in The Matters (2016). "She unsettles the viewer," observes Schlieker, "in a very gentle and interesting way. And you realize that you're looking at puzzles and mysterious constructions that you have to unravel yourself. It's not as easy as it might look at first glance." Enriching our effort to crack the code of her retinal riddles is Yiadom-Boakye's profound knowledge of the past masters that her canvases quote. Much has been made of how the crimson robe of Singer-Sargent's Dr Pozzi at Home (1881) is conflated with the spectral scarlet of the coat that vibrates from Sickert's 1892 portrait of Minnie Cunningham to establish a vibrant bloodline that pulses in the gaping gown of Yiadom-Boakye's seminal painting First (2003) – the earliest work in the exhibition – only to recur in later works such as A Number of Preoccupations (2010).

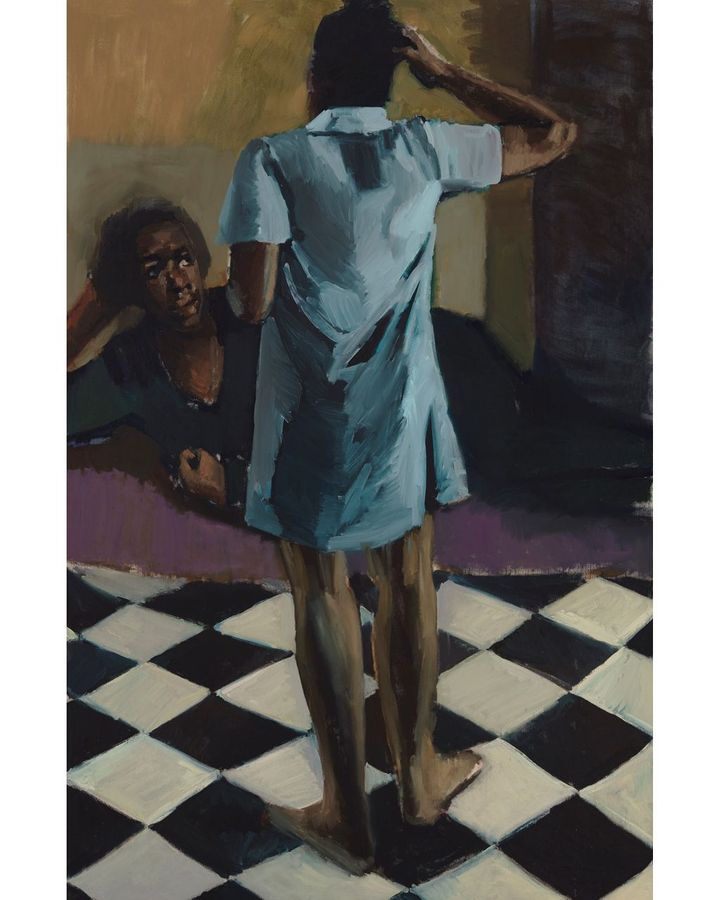

More subtle, perhaps, is the reinvention of the chessboard tiles on which Vermeer has staged his archetypal tableaux, The Music Lesson (1662-65) and The Art of Painting (1666-68). In Yiadom-Boakye's hands, the geometry relaxes into something less rigidly choreographed; something more real. In her recent painting To Improvise a Mountain (2018), for instance, which repurposes the orthogonal tiles from Vermeer's works, an ambiguous drama glimpsed in the clenched fist of the recumbent figure transforms the scene as the urgency of passion supersedes cerebral allegory. Amid all this intense teasing, I can't help wondering if what is really being unraveled and put back together again in Yiadom-Boakye's work is the history of art itself. It is no secret that portraiture in Western art is a Facebook of white power and male privilege. For centuries, the genre knew itself as a luxury of the Empire. In many ways, Yiadom-Boakye's heads turn the conventions on theirs. The dearth of black likenesses in European visual culture has given the artist a yawning void to fill, and a blank slate. Would Yiadom-Boakye, who participated in the acclaimed Ghana Freedom pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2019, ever characterize herself as playing such a role? "Lynette doesn't really like to comment too much on this," says Schlieker, "but she has talked about what she calls 'the infinite possibility of blackness' and of black life, and how she wants to move beyond stereotypes and expectations to a different reality." Still, just in her forties, she already has. What more can anyone ask from art than that?