At 17, James Jeter was certain about where he would spend the next years of his life.

He applied to one college — Morehouse in Atlanta — and was accepted. Seven years after he graduated, Jeter took another leap. This time, it was to share with the head of the iconic fashion designer he worked for, Ralph Lauren, what he really felt about the brand’s blind spots when it came to race and creating what might be considered an unmistakably American look.

During the summer of 2020, after George Floyd’s murder and the protests that followed, Jeter, a concept designer at the time, participated in a company conversation about racial reconciliation where he expressed concerns to brand founder Ralph Lauren.

Jeter, now the director of concept design and special projects, had been working for the company as a part-time salesperson since he was 16, but all along felt that something was missing despite his passion for the brand. He jump-started the partnership by talking to Lauren about his Morehouse experience.

The brand is known for “this kind of aspirational image that has historically been associated with Ivy Leagues and sort of white American culture,” he said. “All the while, these images were kind of alive and well at these amazing HBCUs that are Morehouse and Spelman College.”

Images of the white dress ceremony established around 1900, at which all first-year Spelman students gather in variations of white attire during new student orientation, or Morehouse students, walking through campus in suits for class help to paint a portrait of dignity and solidarity.

Jeter and his colleague Dara Douglas aimed to reflect the ways higher education and expression through clothing had a history of coexisting for many Black people.

Together, the pair designed a collection for Ralph Lauren inspired by the traditions and fashions that tie HBCU students and alumni together for generations.

This was the first time Ralph Lauren curated a campaign with an all-Black creative team and cast.

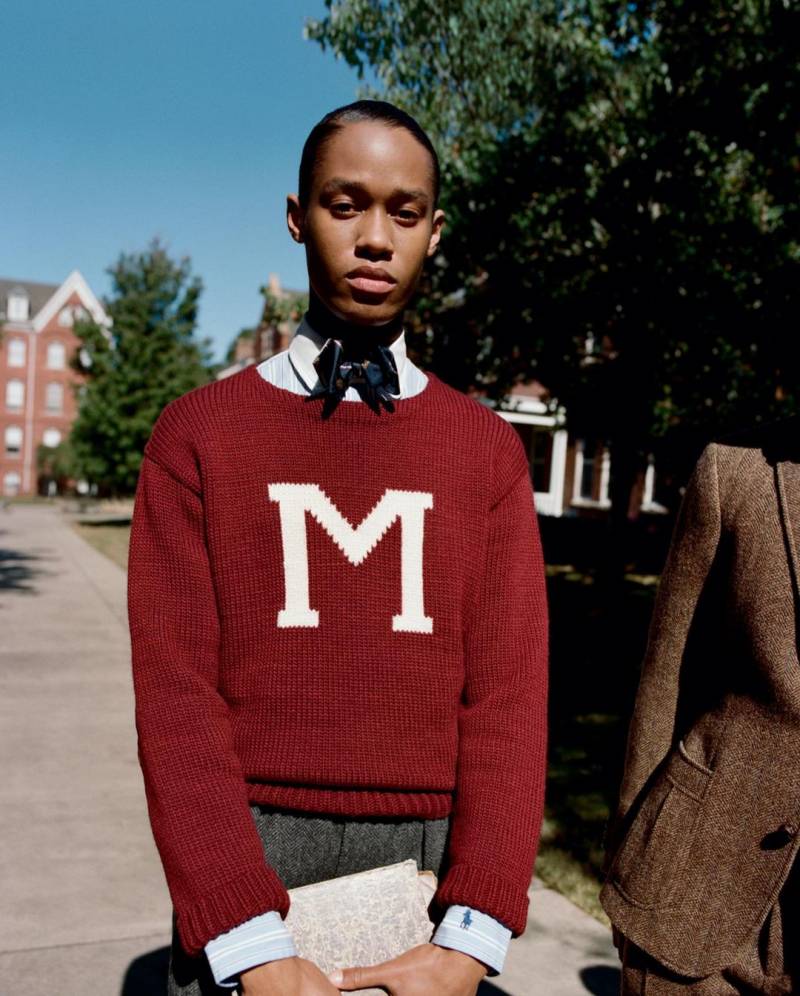

The project includes a photo series shot by photographer Nadine Ijewere where most models were current students, alumni and professors from Spelman and Morehouse. The collection includes white dresses, collegiate sweaters, varsity jackets, and blazers emulating styles from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Jeter had a kindred spirit in Douglas, now the brand and product lead for design with intent at Ralph Lauren. She knew she wanted to attend Spelman College after a campus tour at age 10.

She still vividly remembers when her acceptance letter arrived at her home in a “Spelman Blue” envelope. “I opened the front door, and it falls into the house, and we just screamed and yelled and cried and hugged,” Douglas said.

Though Spelman is a women’s college and Morehouse a men’s, the schools have a unique connection. Their joint nickname, “SpelHouse,” reflects the campuses’ close proximity to each other, to their shared social activity and traditions.

Despite graduating a decade apart, Jeter and Douglas said they felt linked even before their collaboration.

“Because of James’s background, attending Morehouse and being a Morehouse man, I knew that there was a level of trust in his ability and his competency,” Douglas said. “We’re family.”

This familial connection is common among graduates of historically Black colleges. Though each school has different backgrounds and traditions, the foundations are the same: creating space for Black people during a time when exclusionary practices were ubiquitous.

The collection echoes the history of these institutions using fashion to reflect values and self-expression, an experience both Douglas and Jeter could relate to during their respective time on campus.

“You had to show up to Market Friday and Hump Wednesday looking fresh,” Jeter said about the weekly campus social events where Spelman and Morehouse College students gather, often bonding over their outfit choices.

“Yes!” Douglas chimed in.

“It was just the aesthetic of the campus,” Jeter said. “It was just a part of the culture.”

In developing the project, Douglas and Jeter relied heavily on personal experience, careful language and archival images to share what it means to attend an HBCU, an experience foreign to many at the company.

Before we even started talking about clothing, we really started with educating a lot of our leadership around, you know, what does an HBCU mean? Why were they founded? Why are they still important today?” Jeter said.

Tori Soudan, a designer and owner of the Tori Soudan Brand, a collection of luxury shoes and handbags and a Spelman graduate, said fashion is a historical expression of values in the Black community.

“HBCUs are incubators,” Soudan said. “For many people that attend an HBCU, it’s one of the first times where they’re in an environment where they can totally express themselves freely. Fashion naturally plays a part of that.”

Accompanying the project is a film, “A Portrait of the American Dream” and a yearbook, showcasing the collection and the process of creating it, while also educating viewers about the historical relevance of the HBCU experience through the lens of these institutions.

“It’s not just about inspiring Black people. It’s inspiring all Americans,” Douglas said, “inspiring people globally, to just be able to see the beauty in the Black experience.