Stephen Shames had just turned 20 when he visited the headquarters of the Black Panther party in Oakland, California, and showed some of his recent photographs to Bobby Seale, co-founder and main spokesman for the organisation. Though Shames was still finding his way as a photographer, Seale liked what he saw and decided to use some of the pictures in the Black Panther newspaper. So it was that a young white guy from Cambridge, Massachusetts became the official chronicler of the Black Panthers from 1967 to 1973, documenting their community programmes, protests, rallies, arrests and funerals at close hand.

“The Panthers were never a black nationalist organisation,” says Shames, now 74. “They formed alliances with many black writers and activists and their whole legal team was white. They were not out to get white people, as the American government insisted. They were a revolutionary organisation who worked with anybody they felt was sincerely trying to change the system to benefit poor people and create a more just society.”

Since that time, Shames has published two photobooks about that struggle – The Black Panthers (2006) and Power to the People: the World of the Black Panthers (2016) – as well as several other titles that attest to a life of activism and deep engagement with his subjects. Next month, he will complete his trilogy on that era with a book that, as he puts it, is “long overdue”. Co-authored with former Black Panther Ericka Huggins, who is now a writer and educator, Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party is a dynamic visual and oral testament to the crucial role played by women in a revolutionary group whose figureheads, with a few exceptions, were men.

In her foreword to the book, the activist and author Angela Davis points out that 66% of the membership of the Black Panthers was female. She writes: “Because the media tended to focus on what could be easily sensationalized … There has been a tendency to forget that the organizing work that truly made the Black Panther Party relevant to a new era of struggle for liberation was largely carried out by women.”

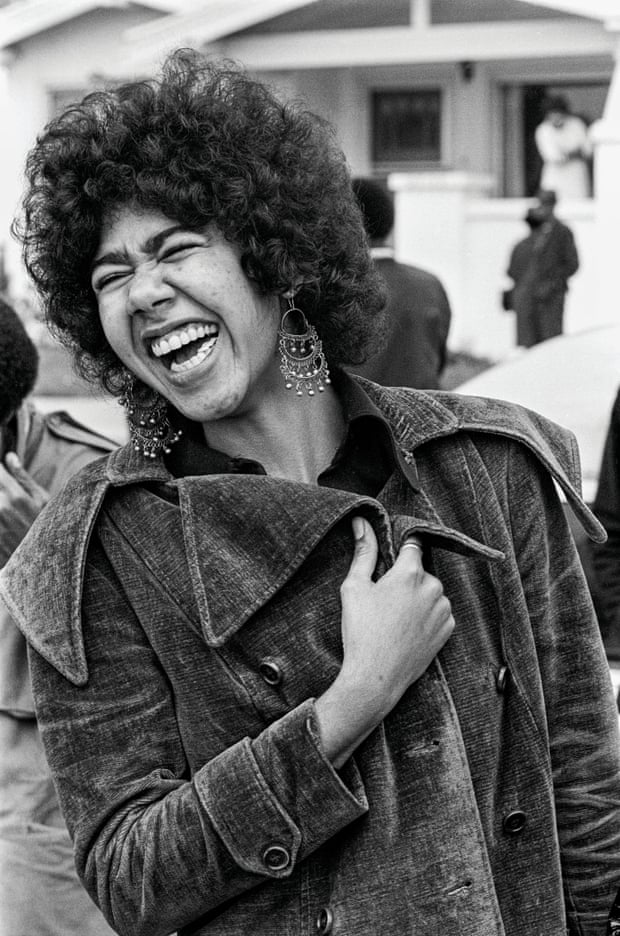

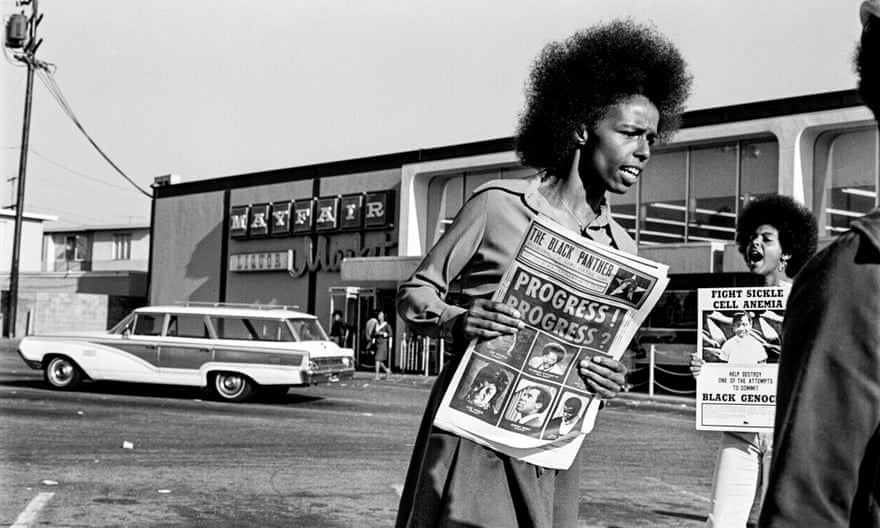

The book is a powerful record of an intense period of grassroots activism and political engagement, a counter-narrative to the one propagated by J Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, who called the Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country”. Like the Black Panther men, the women members tended to look both stylish and dramatic, often sporting afros and at times wearing the black leather jackets and berets that were the Panther uniform. “Most young people are photogenic,” says Shames, “but the Panthers were charismatic. It was something to do with the pride they instilled in their people. Rather than treating them as a problem, as the government did, they gave them a sense of faith and pride and I really think that shines through in the photographs.”

Shames’s extraordinary access allowed him to capture fly-on-the-wall shots of young women at protest rallies, but also carrying out on-the-ground organizing of various Black Panther community initiatives, including the Free Breakfast for Children Program, the People’s Free Ambulance Service and the People’s Free Medical Clinics, which offered medical care, including sickle-cell anaemia testing. Though the series is punctuated by images of well-known female members – Kathleen Cleaver (law professor and former communications secretary for the party), Elaine Brown (prison activist, writer and former chair of the party), and the late Afeni Shakur (political activist and mother of rapper Tupac Shakur) – most of the testimonies come from ordinary black women whose youthful engagement with the Black Panthers remains the most empowering moment of their lives.

Carol Henry, who joined the Oakland chapter of the Panthers, recalls: “I joined the BPP when I was 20 years old. I lived in a part of town where the Free Breakfast for School Children Program ran. We got up at 3am; it was a real mission, but it was beautiful. We gave those children a full breakfast every day. Cooking that breakfast was the most memorable part, because everybody got up so early and everybody worked together.” Another woman, Barbara Easley-Cox, who was in the Philadelphia chapter, remembers: “Love is what tied me to the party; it exemplified how I understood love. And that is: you have to love people, to serve them. I was so loved. So blessed on this earth because of my sisters, all of us, who came into the party. It’s lacking today, when I look out on this landscape in America.”

As co-author, Ericka Huggins wrote the introductory essay and tracked down, as she puts it, “the women who were there and whose individual testimonies we could use to evoke how extraordinary that time was for many of us”. Huggins’s own moment of political awakening was seismic. Aged 18, and a student at Lincoln University in Philadelphia, she picked up a copy of the radical leftist magazine Ramparts and saw a photograph of a young black man strapped to a hospital gurney with a bullet wound in his stomach. Next to him, a policeman stood grinning at the camera. On reading the accompanying report, she found out that the young man was Huey P Newton, a co-founder of the party, who had authored the party’s 10-point manifesto with Seale in 1966. “I studied the picture for some time,” she recalled years later, “I didn’t have tears for it, I was so appalled.”