New York’s Jack Shainman Gallery now represents the rising artist Ifeyinwa Joy Chiamonwu, who will have her first solo exhibition with the gallery in January.

A self-taught artist who learned to hone her craft by watching art instructional videos on YouTube, Chiamonwu has quickly established herself as an artist to watch for her hyper-realistic portraits of Nigerians in charcoal, acrylic, and other mediums. Her work was recently shown in a group exhibition at Black Wall Street Gallery in New York.

“When Nigerians see my art, I want them to immediately feel the connection that these are my people,” said Chiamonwu, who is based in Anambra.

The 25-year-old artist is set to join a roster that also includes a number of well-established figures, among them Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, Hank Willis Thomas, Malick Sidibé, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. In the last few years, the gallery has also been influential in supporting a younger generation of rising artists, including Toyin Ojih Odutola, Paul Anthony Smith, and Tyler Mitchell. Chiamonwu’s show next year will mark her first solo exhibition ever.

“There is a striking sense of vivacity and intimacy in her sitters, and the technique and skill required to achieve this is well beyond her 25 years,” said the gallery’s founder Jack Shainman in an email. “At first sight, I noticed how each image included figures that are deeply personal to Ifeyinwa. While I was not aware of just how close she was to them—she draws inspiration from her family, close circle, and culture—I could easily see the care and intimacy she utilizes to construct compositions that draw you into her world and space.”

Though she has been drawing since childhood, Chiamonwu only began to seriously focus on her art in 2015. She attended the Nnamdi Azikiwe University in Awka, Nigeria, and received her degree in education. Her experience in learning how to teach has become an indelible part of her artistic practice.

“I love storytelling, and I try to incorporate that into my art,” she said. “I’m trying to educate people through my artwork. I’m focused on showing my traditions, my culture, my heritage because it’s going through a form of extinction now because of Westernization and technology. I’m trying to preserve that.”

A hyperrealistic black-and-white drawing of an Igbo woman in traditional dress with seashells in her hair at work weaving a basket.

In works made between 2018 and 2020, Chiamonwu depicts Black Africans dressed in traditional Igbo clothing with painstaking detail. In Lost Page (2018), a woman whose natural hair is bedazzled with seashells weaves together a basket, while Abundance (2019) shows a man’s hands holding a surplus of seashells. For Chiamonwu, she wants to show her fellow younger Nigerians—both those living in the country and those who are part of its diaspora living abroad—their own culture. The goal is to portray “who we are and where we come from, as in everything about that in terms of the myths, the traditions, the culture,” she said.

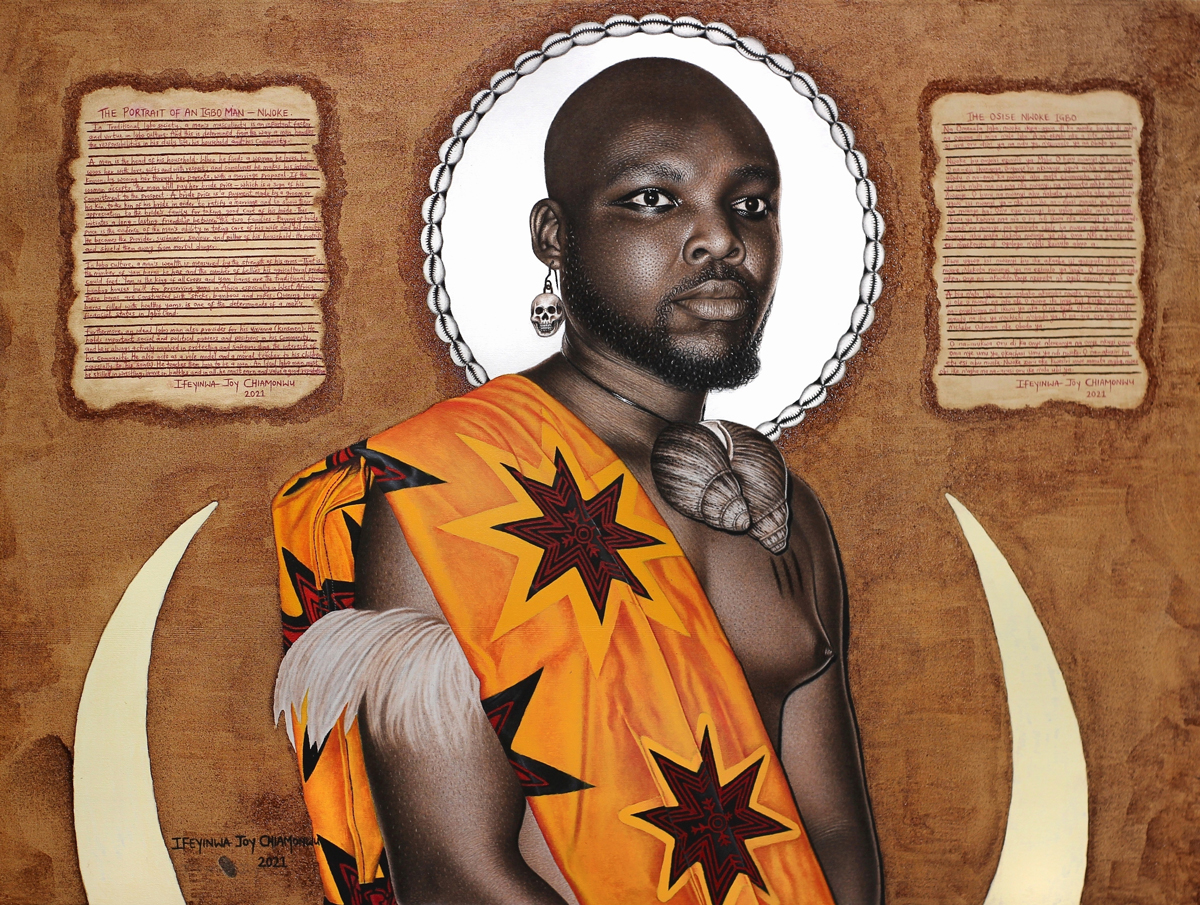

For a new series, Chiamonwu has begun to incorporate text alongside her portraits in both English and Igbo to provide further context for the people she is depicting. Text that is part of the composition for The Portrait of an Igbo Man–Nwoke (2021) reads, in part, “[A]n ideal Igbo man also provides for his umunna (kinsmen). He holds important social and political powers and positions in his community, and he is always actively involved in protecting and safeguarding the interests of his community.”

A hyperrealistic drawing of an Igbo man wearing an orange traditional garment, a necklace of seashells, an upper arm piece of feathers. His head is surrounded by a white halo. On either side is a description in English (left) and Igbo (write) about Igbo men.

Chiamonwu said that her decision to incorporate text into her work is partly a way for her to experiment within her practice, as well as a way to educate “people who are not from my place, who are not African, who are not Black,” she said. “The more I write on the work, the longer it will stay for years to come.”