This weekend, a new museum opens in London dedicated to female genitalia – helping to lift a taboo that runs all the way back to the birth of Western art, writes Holly Williams.

In 2017, Florence Schechter discovered that Iceland had a penis museum, but that nowhere in the world could its female equivalent be found. And so, the science communicator decided to do something about it. This month, in London, the Vagina Museum will be born.

In fact, it’s a pretty different proposition to the penis museum. “That’s kind of novelty, penises in jars,” Schechter explains. “We’re going to be much more thoughtful and actually explore the topic.”

First up, a note on the name. Schechter acknowledges the frustration at how the word “vagina” is often used when people are really talking about the external vulva (the labia, clitoris and vaginal opening) – but they needed a term people were already familiar with.

“A lot of people don’t know the word vulva, and people are not going to engage with something they don’t know,” she says. A Vagina Museum is, frankly, more eye-catching and conversation starting.

The Vagina Museum in London has been set up by science communicator Florence Schechter to look at the entire gynaecological anatomy and its representation (Credit: Nicole Rixon)

The museum will look at the entire gynaecological anatomy – the inside (uterus, cervix, ovaries) as well as the outside – and consider its representation in culture and history. But the fact a Vagina Museum needs a bit of a glossary in the first place is proof of its purpose.

“The gynaecological anatomy is a very stigmatised part of the body,” points out Schechter. “A museum is a place where conversations can happen – the best way to fight taboo and stigma is with knowledge.”

We are still crushingly bad at talking about all the bits between women’s legs – often ignorant or euphemistic, vague or embarrassed, even if we have a vagina ourselves. And wider culture attitudes to them run the gamut of sniggering, censorious, disgusted, objectifying, or actively oppressive.

A culture of fear

This inability to talk about female genitalia has certainly had its impact on Western art and culture. Taboos can make an image more powerful – but they can also lead to fearful depictions of the unknown, or to the erasure of a huge part of lived female experience.

Let’s start at the beginning: birth. Where are the paintings of birth in Western art? They don’t exist, prior to the 20th Century. This curious lack has been pointed out by the novelist and essayist Siri Hustvedt. “It is a stunning absence,” she says, adding that the suppression of gestation and birth has to be “related to the suppression of women and the fear of women.”

There is still a cultural paradox and hypocrisy around vaginas - Emma EL Rees

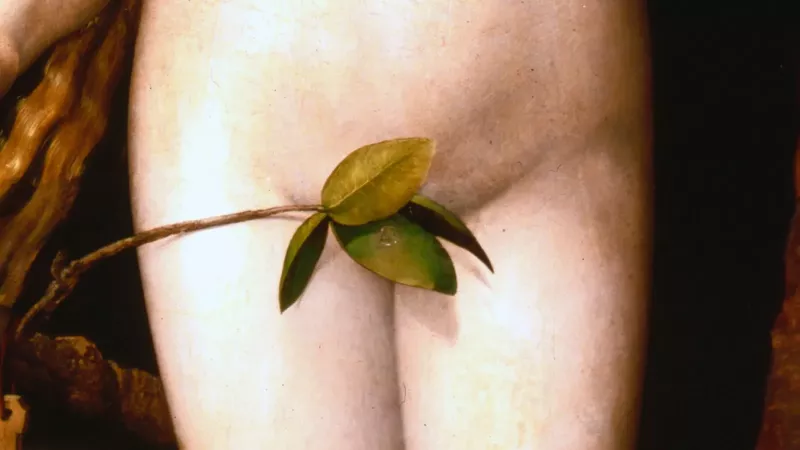

It’s also surely to do with a religious tradition of painting where the female figure is a virgin: distaste for the visceral elements of reproduction have been coded into art right from the start... “It is an example of the vagina getting written out of a dominant cultural narrative,” agrees Emma EL Rees, Professor of English at the University of Chester.

As the author of The Vagina: A Literary and Cultural History, Rees literally wrote the book on the depiction of vaginas – and its chapter on birth shows that, even in modern times, public attitudes to seeing women’s private parts during childbirth are fraught.

Sheela Na Gigs – figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva – are found in Norman churches all over Europe (Credit: Alamy)

In 1997, UK artist Jonathan Waller’s life-size paintings of women were apparently considered so distressing by the gallery who represented him that they removed one of them from a show; later, the images prompted the Independent on Sunday to ask ‘Is birth the last taboo subject in art?’ Rees shares another, more recent example: at a 2009 exhibition of the Birth Rites Collection – work dedicated to the artistic depiction of birth, first displayed at Salford University before moving to various galleries and science centres across the UK – a photograph by Hermione Wiltshire of midwife Ina May Gaskin called Therese in Ecstatic Childbirth, which shows a mother’s joyful expression at the moment of crowning, was apparently repeatedly covered up by visitors.

“There is still a cultural paradox and hypocrisy around vaginas,” Rees tells me. “The same people who will criticise seeing a baby crowning potentially consume porn – [then they are] perfectly happy with vaginas, but when they start doing stuff like pushing another human being out of them, that’s somehow obscene.”

The fear of the unknown-ness of the vagina becomes a rationale for acts of extreme brutality - Emma EL Rees

Rees was drawn to documenting cultural depictions of vaginas for the same reason Schechter wanted to make a Vagina Museum: because there’s still so much silence and ignorance around them.

One of the spurs was an encounter, outside a church in Kilpeck in Herefordshire, with a stone carving of a woman holding open her vulva – and the fact that a 19th-Century guide to the church claimed that it was a fool holding his chest open. “That’s not a fool, and that’s not a chest!” Rees recalls, laughing.

In the 2007 horror Teeth, the young, innocent heroine Dawn has a vagina dentata that bites the penis off someone who tries to rape her (Credit: Alamy)

In fact, what she was looking at was a ‘sheela na gig’ – figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva – the word for which is familiar to PJ Harvey fans thanks to her song of the same name (“Look at these, my child-bearing hips/Look at these, my ruby red ruby lips”, she sings – not the first or by any means the last time a pop song has capitalised on the dual meaning of lips). The carvings are found in Norman churches all over Europe, and while their purpose isn’t entirely understood, it may be to do with promoting fertility, healthy births, or warding off evil.

The autonomous vagina

Still, compared to male genitalia, depictions of the vulva are pretty rare until the 20th Century. Of course, female sexual organs are more hidden compared than their masculine counterparts – and this, combined with the lack of non-sexualised discussion of, and language for, the female genitals seems to have had a real impact on the depictions that do exist. I was struck, reading Rees’s fascinating book, how many examples present the vagina either as autonomous – rebellious, or oddly divorced from its owner – or as a terrifying, dangerous thing.

One mythic image goes way back: the vagina dentata – a vagina armed with teeth, that damages or castrates the male. “It’s a myth that has a history and currency in cultures and civilisations that could not have communicated with each other: in the Indian subcontinent and in south America we get the same stories emerging, at a time when there wasn’t any transatlantic travel,” says Rees. She adds that in many of these myths “the fear of the unknown-ness of the vagina becomes a rationale for acts of extreme brutality – knocking the teeth out through rape or serious sexual assault.”

Rees also references several modern manifestations of this Freudian fear, not least US director Mitchell Lichtenstein’s film Teeth. In the 2007 horror, the young innocent Dawn’s crush Tobey tries to rape her, only for her vagina to chomp his penis off. Dawn goes on to learn how to use her vicious vagina to wreak revenge on sexually predatory men.

One reason why I show my cervix is to assure the misinformed that neither the vagina nor the cervix contains any teeth – Annie Sprinkles

The myth of the vagina dentata played a part in performance artist Annie Sprinkles’s droll work, Public Cervix Announcement. Performing it live during the 1990s, she’d open her vulva with a speculum, and invite audience members to shine a torch inside her and speak into a mic about what they found. You can now experience the work on her website – where she comments “One reason why I show my cervix is to assure the misinformed, who seem to be primarily of the male population, that neither the vagina nor the cervix contains any teeth. Maybe you’ll calm down and get a grip.”

In Netflix animation Big Mouth, the female lead Jessi has a vagina - voiced by Kristen Wiig - that is very much its own character (Credit: Alamy)

Sprinkle let others speak about – for? – her genitals, but there’s also a long history of the chatty vagina: an organ that speaks a truth its owner can’t, won’t, or doesn’t want heard.

“The idea of the autonomous vagina was one I began to see a lot of [in my research],” says Rees, who believes that our general inability to discuss vaginas has led to women often feeling separated from their own anatomy. But there’s also a tradition in art and literature of men controlling women by forcing their vaginas to mutter…

Rees’s examples go as far back as Medieval French poetry, and the story of Du Chevalier Qui fist les Cons Parler. After a magical power is bestowed on a knight by three witch-like women that allows him to address women’s private parts, he uses it to cause much mischief at a castle. The women have no control: whatever he asks, their vaginas will reply with the truth.

Truth-telling vaginas also appear in the 18th-Century French writer Denis Diderot’s Les Bijoux Indiscrets, in which a genie provides a sultan with a magic ring that can command “the most honest part” of women to speak the truth. He mostly uses it to question women’s fidelity – a clear instance of how male anxiety about women not being truthful has long been bound up with anxieties about their sexual appetites. And, of course, another example of a man forcibly controlling a woman’s body.

In South Park, Hillary Clinton had a vagina dentata which ate a man’s head

More recent examples of blabbing genitalia include the 1977 US film comedy Chatterbox, in which the heroine Penelope’s vagina – dubbed Virginia – starts to speak and even sing. Although Penelope worries her vagina is a “foul-mouthed little beast” who just wants to have sex all the time, Virginia soon becomes quite a star. Once again, there’s a disconnect between a woman and her vagina: the film riffs on the idea of it being more liberated and honest than its owner, while Penelope silently suffers shame.

And it’ll surely come as no surprise that South Park has animated various talking lady parts, usually in order to undermine women of power. One episode saw Oprah Winfrey given an autonomous vagina that was dissatisfied and demanded more attention. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, had a vagina dentata which ate a man’s head. Then again, the South Park movie, made in 1999, did feature a more benevolent talking organ: the mystical, near-mythical clitoris.

Writer Eve Ensler amplified the conversation about vaginas with her hit play The Vagina Monologues (Credit: Getty Images)

But vaginas can also speak for their owners, not against their wishes. Artist Carolee Schneemann’s infamous 1975 work Interior Scroll saw her undress, pull a scroll out of her vagina, and read it: the text recounted a discussion Schneemann had about her work with a patronising filmmaker who thought her work was too messy, too concerned with feelings.

The pleasure principle

From the serious to the silly: Netflix’s Big Mouth is another cartoon about teenagers featuring plenty of chatty body parts. But in contrast to South Park, Nick Kroll’s comedy about middle schoolers going through puberty is good-hearted, level-headed, and actually full of sound advice. Pubic hairs, raging hormones, and vaginas all get personified. But it’s notable that the while female lead Jessi’s vagina is separate from her and very much its own character (as voiced by Kristen Wiig), when she talks to Jessi it’s to encourage her to discover how much fun they could have together. “It’s an honour to be a part of you,” she says, toasting Jessi after their first orgasm. This vagina is promoting unity through pleasure, not shame or separation.

Pleasure: a pretty important function for any owner of a vagina – and yet depressingly not that often the focus of art. With the vagina having been largely hidden, pornography aside, for centuries, just achieving visibility seems to have been a real challenge – and the most famous works have tended to attract virulent criticism from both men and women. Take two of the most famous examples: Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation The Dinner Party and Eve Ensler’s 1996 play The Vagina Monologues.

Chicago laid three tables for an imagined party of 39 women, among them goddesses, queens and 20th-Century icons including Virginia Woolf and Georgia O’Keeffe (whose own flower paintings have often been interpreted as evoking vulvae, although she denied that was her intention). Alongside gold chalices, embroidered napkins and runners, it features plates shaped as individual, abstracted, butterfly-like vulva.

It’s a monumental work, but attracted scorn from male art critics when it opened and for years after (the Los Angeles Times art critic called it “a lumbering mishmash of sleaze and cheese”; the New York Times later deemed it crass, vulgar, and didactic). The work also attracted the ire of some feminists who claimed it reduced women and their achievements by focusing on their genitals. Museums cancelled showings of it, Chicago struggled to find a home for the work (happily at the Brooklyn Museum since 2007), and its notoriety overwhelmed her career.

Judy Chicago's installation The Dinner Party (now in Brooklyn Museum) features vulva-shaped plates (Credit: Getty Images)

And yet the work has always been wildly popular with the gallery-visiting public, and especially women. Chicago was surely feeding a hunger, a need, with The Dinner Party. And you could argue the same for Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues, a work drawn from interviews Ensler conducted with women ranging from a six-year-old to a septuagenarian, from Bosnian war survivors to a sex worker for women, that touches on sex, periods, body image, rape and female genital mutilation (FGM).

It’s not all bleak: the monologues also feature joyful sex and multiple orgasms. Ensler’s show has become an international phenomenon, performed all over the world on 14 February each year, also known as V Day, an initiative started by Ensler raising money to end violence against women. It’s a feminist text that’s proved palatable to celebrities too: everyone from Alanis Morrissette to Glenn Close to Oprah Winfrey has had a go at appearing in it.

Still, the hyper-visibility of Ensler’s show has also drawn seemingly endless criticisms: it’s been deemed too smug, narrow in focus, insufficiently radical, essentialist, colonial, or maybe even simply – whisper it? – too successful. But whatever swipes people take at Ensler, the play genuinely did help bring conversations about vaginas into the mainstream.

And it does feel like we might be moving into an era where we’re seeing more depictions, not just of female sexual organs, but also female sexual pleasure. Artists in the 21st Century seem to be able to depict vaginas without it necessarily having to be traumatic or taboo-busting.

Ariana Grande’s video for God is a Woman is obvious enough for everyone to be like: that’s an ode to the vulva – Florence Schechter

Take UK writer and actor Bella Heesom, who the Guardian suggests “might be considered Ensler’s millennial heir” thanks to her show Rejoicing at Her Wondrous Vulva the Young Woman Applauded Herself, which encourages women to love themselves too. Staged in London earlier this year, the show includes a light-up clitoris headdress, and puts the joy of masturbation and orgasms onstage.

In visual art, New York-based Ghada Amer uses embroidery in her colourful, outlined images of women masturbating; she hopes the needle-and-thread can bring a tenderness to such images that “simple objectification ignores”. Tschabalala Self’s bold, colourful work also blends collage and sewing, presenting powerful, confident black women, often opening exaggeratedly wide thighs or curvaceous buttocks to reveal their genitals – a colourful heart, perhaps, or a burst of rainbow.

Artist Megumi Igarashi is best known as the maker of the “pussy boat”: a canoe modelled on a 3D scan of her vulva (Credit: Alamy)

Pop music has done its bit too: music videos have always been sexually suggestive, but more recently female artists have been playing with knowing visual innuendo to make it clear they’re singing about their own pleasure. Take Ariana Grande’s video for 2018 single God is a Woman, for instance, where she writhes around in various suggestive pools, flames, and (lady) caves – and is at one point backed by a choir of actual screaming beavers. No wonder the video is one of Schechter’s favourite pop-culture depictions: “it’s obvious enough for everyone to be like: that’s an ode to the vulva,” she says.

Why can’t vaginas be funny?

Or take Janelle Monae’s fantastic video for last year’s Pynk, her hymn to “self-love, sexuality and pussy power”. Monae and her female dancers perform in vulva-like trousers, and the video is loaded with pink visual stand-ins for vaginas: milkshakes, ice cream sundaes, oysters, and grapefruits.

She’s not the only one getting fruity: LA-based artist Nevine Mahmoud makes gorgeous sculptures out of marble and alabaster that somehow look warm and sensual: peaches split to reveal a peek of stone, softly folding lilies (which Mahmoud deems “the most erotic flower”), and a cleft shape called Fig/Vagina.

The erotic potential of fruit is also brilliantly exploited in the videos of American multimedia artist Stephanie Sarley: she gently rubs halved pieces of fruit in a circular motion – then inserts her fingers till they squirt. They’re glorious and ridiculous, and yet reveal that, even now, the mere suggestion of female ejaculation can be controversial. In one month in 2016, Instagram suspended and restored Sarley’s account three times – a blood orange in particular attracted vitriol – although Sarley’s stated aim is to promote greater acceptance of female sexuality via humour.

Women’s bodies are so often offered as purely sexual, it can be a liberation to celebrate the grotesque, the weird and often hilarious functionality of the body – Lucy McCormick

But artists at least trying to say that women’s sexual bits can be funny – in the same way that penises certainly often are – is surely a cheering development. British performance artist Lucy McCormick has also garnered a reputation for eye-poppingly explicit, eye-wateringly funny shows, that send up the ridiculous expectations of performative female sexuality.

“Women’s bodies are so often offered as purely sexual, it can be a liberation to celebrate the grotesque, the weird and often hilarious functionality of the body,” she has said. Her current show Post-Popular, for example, sees her taking the idea of searching for a hero inside yourself very literally: she pulls a Cadbury’s Miniature Hero out of her vagina, and eats it.

Another visual artist who’s been explicit about using humour is Megumi Igarashi, best known as the maker of the “pussy boat”: a canoe modelled on a 3D scan of her vulva. But in 2014, when trying to raise funds to make it, she got in hot water: Igarashi was arrested in her native Japan after selling data enabling people to make 3D prints of her vagina. She was fined 400,000 yen – then about £2,575 – for distributing obscene images, despite insisting she was innocent. Her defence was spot on: she refused to accept that “artworks shaped like female genitals are obscene.”

Such censorship proves we’re still far from being as comfortable with vaginas as we should be, even if creative depictions of vaginas and vulvas in all their varied glory – messy, silly, funny, sexy, beautiful, and empowered – do seem to increasingly be able to take a place at the table. Not to mention, at last, being given a museum all of their own.