©

On August 11, 1973, Kool Herc DJed his sister’s back-to-school party in the rec room of 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx. Emulating the sound-system culture of his native Jamaica, the teen set up two turntables, dropped a copy of the same record on each, and began cutting back and forth between the two, playing only the percussion breaks.

In a flash, Hip Hop was born — and the new style of music quickly caught on. Although it didn’t yet have a name, it was quickly making waves. At parties, Herc would call out, “B-boys go down,” inviting the dancers in the crowd to show and prove. MCs would get on the mic, emulating the reggae style of toasting. Their chants became bars, those bars became raps, and within a decade Hip Hop was on wax.

In 1982, Charlie Ahearn released Wild Style, which brought together the four elements of Hip Hop culture for the very first time on film. The movie introduced the world to the pioneering DJs, MCs, breakers, and graffiti writers who were still very much underground, creating and innovating in what would go on to become a multi-billion dollar music industry.

© Frankie Perez

Although breaking was popularized in the ‘80s, like many forms of dance it proved difficult to commodify for an extended period of time. While the mainstream treated it like a fad, discarding it after they could no longer capitalize on its creativity, breaking continued to evolve worldwide, while staying closely connected to the roots of the culture.

Over the past half century, breaking’s singular combination of athleticism and artistry has appealed to people from all walks of life, becoming a language that transcends borders of every sort. In 2024, breaking will make its debut at the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, showing the world just how far it has come since B-boys and B-girls were doing backspins and windmills on cardboard boxes.

Get on the Good Foot

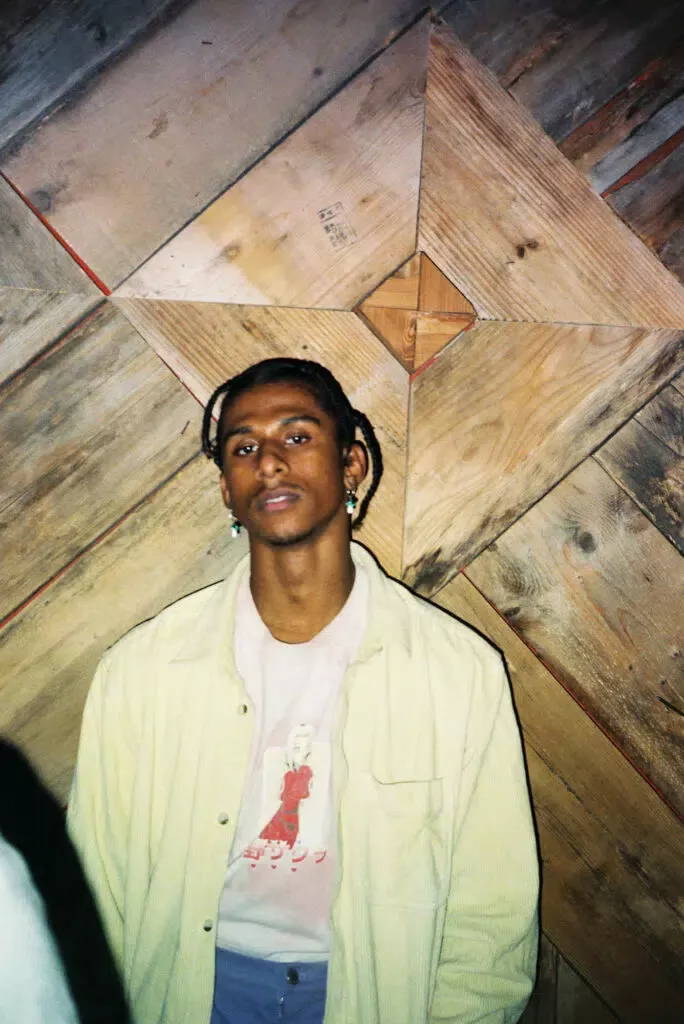

Hailing from New York City, photographer Frank “B-boy Frankie” Perez first got into breaking in 2002 at age 13, when a neighbor showed him some moves. They’d watch VHS tapes together, then practice moving in the kitchen. Perez was hooked and started going to a local practice spot where he could train alongside more experienced B-boys.

© Frankie Perez

“It felt huge to me. As someone growing up in Queens where I hung out in a 10-block radius as a kid, it felt as if the world was starting to open up to me,” says Perez, who eventually felt confident enough to compete. “Sometimes going to a different borough to practice or for an event really felt like a different world.”

By the time Perez was 19, he started making videos of his own — small reels that were montages of his travels, featuring himself and his friends, that resembled old school skateboard videos. ‘It was all very rough but there was a beauty, innocence, rawness that I find very beautiful now,” he says.

© Frankie Perez

© Frankie Perez

As his interest in visual culture deepened, Perez began studying art, photography, and film in order to expand his understanding and sense of possibility. In 2015, at age 26, he began focusing on photography, finding joy and release in the freedom of the still image.

Disappointed in the mainstream media’s representation of breaking, Perez set out to create an authentic portrait of the culture. In true DIY fashion, he secured a grant from the Queens Council of the Arts to produce See Me Up? It’s ‘Cause I’ve Been Down, a self-published artist book featuring photographs taken around the globe between 2018-2020.

Amen, Brother

Today, Frankie Perez is focused on using photography to expand the ways breaking is viewed at a time when the mainstream is finally beginning to recognize that B-boys and B-girls have been here all along. On March 3, he attended “Descendants of the Break,” which was organized by Red Bull BC One, the most prestigious solo B-boy battle in the world. “The event was a way to pay respect to what breaking is at its core: community jams, spontaneous battles, and open cyphers in the place where it started — New York,” he says.

© Frankie Perez

As a self-taught dancer and photographer, Perez understands that the intergenerational appeal of Hip Hop culture lies in its “something from nothing” ethos that creates accessibility. “Unlike another dance style that might be considered more ‘sophisticated’ on the surface, I never needed to pay anyone to teach me how to break nor did I need to buy any particular clothes to get started,” he says. “I don’t think breaking will ever fade out for the same reason rap music will never fade out. Our movement keeps evolving and there will always be those who want to push further and further.”

For Perez, the same could be said of his approach to photography, which adopts a more fluid and abstract approach, much like breaking itself. “I’m no longer interested in just straight forward documentation of the culture,” says Perez, who is currently focused on qualifying for the U.S. Olympic Breaking Team. “Where I’m at now is a period of dreaming out loud.”