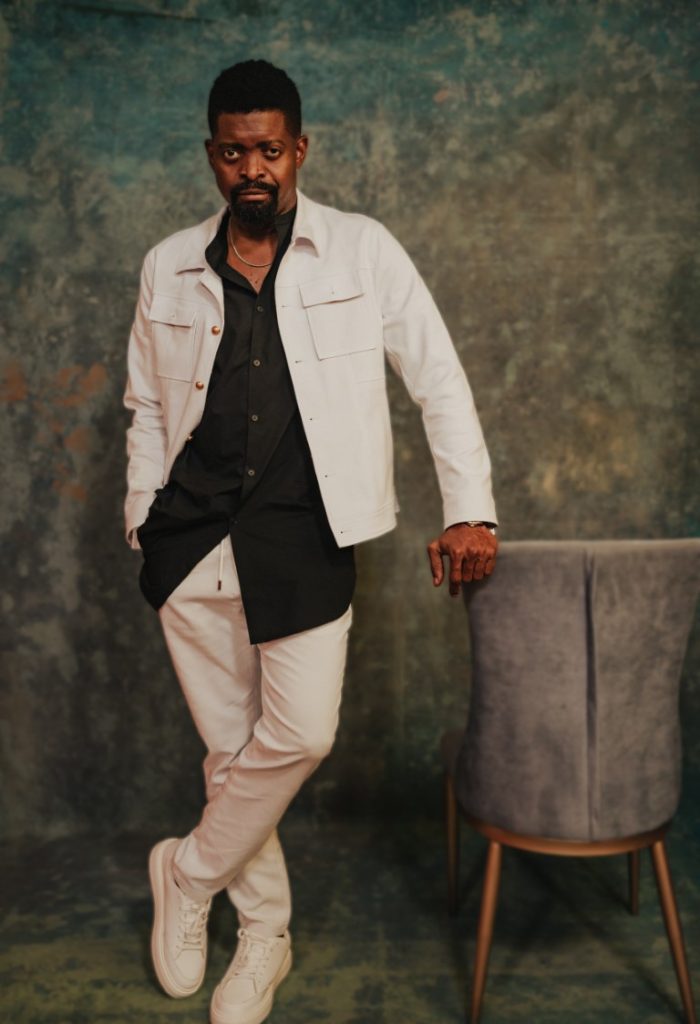

Transitioning within the entertainment industry, although reported as clearcut as possible, is a challenging thing to do. Each of these art forms we casually consume is different stakeholders actively living their dreams, one that they have nursed for practically their whole lives. With Bright Okpocha, widely known as Basketmouth, every dream is worth attending to. This is why he took a break from music to establish himself as the biggest name in Nigerian comedy, thanks to years of consistently cracking people up. Twenty-four years later, Bright is not just back to making music; he is doing it at the highest possible level—production.

In almost three decades of marinating himself in the deep fruitful waters of Nigerian entertainment, Bright has gone on to not only tell jokes but rap, act, produce and direct some of the country’s biggest films, TV series, and concert events. All of these culminate in a career so multifaceted one cannot predict what his next creative move might be. DOWNTOWN’s Editor, Onah Nwachukwu, sat with the multi-talented artist to chronicle his journey from forming a rap crew that went by the name ‘Da Oddz’ in the late 90s to touring the world with comedy and deferring an invite to produce his own Netflix Standup.

You were a part of a music group years ago. How did you make the transition to comedy?

Even as we made music, almost everybody— my childhood friends—in that group was funny, but I didn’t realise that being funny was a talent. I thought that people should be funny because everyone around me at the time was funny, most of them even funnier than I was. So when we formed the group, comedy was still a part of it because when we were rapping, I was still trying to make people laugh. We always take breaks to crack jokes. But the music never got launched in the true sense of it because, at the time, although we were doing shows and university tours, we were an up-andcoming rap crew, so we never really got into the music scene until I broke into comedy, of which, it took me another 24 years to go back and do it. Even today, one of the guys, Dominic—his rap name is Item 7—is based in Austria, making his music as an aside to his nine-to-five. My brother is doing something similar as well, non-commercial music for now. As for me, my nine-to-five is comedy and TV, and I still make music because it is just my thing.

Would you say coming back to music was always the plan or something that just aligned?

It was part of the plan. When we started rapping, the music industry in Nigeria wasn’t commercial. Also, there was a disconnect because we were influenced by The Wutang Clan and other foreign rappers but no Nigerian rappers. This was when the only people doing rap in Nigeria were Junior and Pretty, who were underground artists. At the time, I said to myself, ‘Bright, this is not going to go anywhere.’ That was based on foresight which I think is something God blessed me with. So I decided to focus on comedy, knowing I would someday return to music. At the time, the music I wanted to create was different from the kind that trends. The first album, Yabasi, was an experimental work. I love that I completed that journey because I had decided to blend Igbo highlife and hiphop like 25 years ago, and I’m happy I waited 25 years and still did it, and it worked. So it was like a dream come true.

In addition to comedy, TV and music, you are also into event production. How would you say you tally all three?

TV requires music on a large scale. I jumped into music because I was making Papa Benji, and the show needed a lot of music, and I wanted to avoid going to get music from people. So I saw it as the perfect opportunity to create my own music, bearing that I had just met a brilliant producer, Duktor Sett. Blending film and music is easy for me because they complement each other. The only thing that is difficult in making music is the promotional aspect of it. But blending TV and stand-up is very difficult because, with TV, you shoot almost every day. On Flatmates, we produced about 260 episodes a year. That involved shooting every work day of the week. My brother and I joined a ‘performing students’ organisation in school as a rap crew. Because most of us had left the country, we decided to call ourselves ‘Da Oddz.’ For our first show has Da Oddz, I was in Ekenwa campus in Uniben(University of Benin). The show was called 300 Men Groove, and the MC/comedian was doing a terrible job, and the crowd was upset. I told Dotun, who is still my manager, “I can do this thing better.” He spoke to the show promoter, who had doubts as I was billed to perform as a rapper. But he didn’t have anything to lose as the audience was increasingly annoyed by the MC. So he gave me five minutes, and I ended up doing 45 minutes. I did so well telling the silly little jokes that the audience kept hitting their desks in excitement. It felt really good. The next day as my friends and I got to a restaurant to eat, people kept walking up to me saying, “Bright, you killed it last night,” because we had an outstanding performance as a rap crew, and I entertained the crowd as a comedian. I even had someone pay for my food, which felt so good because I didn’t have enough money to feed myself then. So I was like, ‘if this is the way to eat, then I’m going to do all the gigs.’ And that was how it started.

How did you break into comedy shows outside school?

One time, one of my friends at Delta State University, Abraka, told me about a show happening in my school, Uniben, with Alibaba performing. So he came to Uniben to watch the show and bought a ticket for me, it cost 50(Fifty) naira at the time. I sat there and watched Alibaba perform for the first time because I hadn’t seen a Nigerian comedian; I didn’t know how they did it. At the end of the show, while everyone was laughing, I was having a general meeting in my head. I wanted to meet him but couldn’t get through to him. I heard that the show was annual, so I knew I needed to work myself up to the point where I could open for him the next time he came. I started doing all the gigs available in school. I would work my way into any faculty doing their end-of-the-year party to perform there. I was getting paid for a few of the shows, but I didn’t really care about the money. Eventually, word went around, and I got called to perform at the next Alibaba show. I was satisfied. When it was time for the gig, they put me first because I’m young and new, so I begged them to move my performance towards the end of the up-and-coming acts. Alibaba hadn’t come, and if I had performed earlier like I was scheduled to, Alibaba wouldn’t watch my performance. So I tried my best to avoid being called. I hid and told people to beg the show’s producer for me. He eventually agreed, and I performed my set when Alibaba was in the audience. After my performance, he, alongside everybody else in the hall, gave me a standing ovation. That was how comedy started because he gave me his card and told me to look for him whenever I came to Lagos. I didn’t even wait [laughs].

You’ve been doing a lot more concerts and events these days. Is that something you are going to continue with?

Yes. With concerts, I have been producing shows for a while. Most things started in Uniben. We weren’t getting a lot of shows in school back then, and I had access to the likes of the Remedies and Plantashun Boiz based on the fact that I was a rapper— we used to hang around then, Tuface knew me as a rapper, I opened for the Plantashun Boiz even before Faze joined them. So I said, ‘I know these guys; why don’t I bring them to school?’ So I brought together four guys and told them about my plan to bring the Plantashun Boiz to school and the cost implications. I told them the show was on a 150,000 (one hundred and fifty thousand) naira budget, so I asked them for 30,000 (thirty thousand) naira each, and they trusted me based on the entertainment I’d been doing at the time. They all paid their quota, adding up to 120,000 (one hundred and twenty thousand) naira, which was the exact amount I needed (laughs). I didn’t have 30,000 (thirty thousand) naira. How? When I was receiving N300 (three hundred) naira per gig (laughs). Yeah, now my friends know the truth](laughs). I then got Tuface at a discounted rate because, typically, the show would have cost me about 200,000 (two hundred thousand) naira. (Oh my God, I’m too smart [laughs].) Of course, the show sold out; it was Plantashun Boiz live in Uniben. After that show, I spoke to my friend, Bayo Adekeye. His father was a senator, so he had some connections. At the time, Bayo had a company called Baron’s World Corporation. I liked the name and asked if I could open a company and call it Baron’s World Entertainment. He liked the idea and said we should do it. We needed to be more creative, seeing that we were now a company, even though we hadn’t registered it at the time. We did a gig called Laugh and Jams and had Alibaba perform. So I went to Alibaba’s office and told him, “boss, I’m doing a gig and would like you to perform.” And he did it for me for free. All he asked of me was to come to Lagos so that we could drive to my school together, so we drove down in his car, and he checked himself into a hotel on arrival. After that, we had a show called Splash cancelled because of a riot in school. It was supposed to be a pool party with DJ Jimmy Jatt. So I took Laugh and Jams to Ekpoma and began to feel like a show promoter. I came to Lagos and figured I had to step things up, so I registered the company. I also brought Laugh and Jams to Lagos, and we did it for two years. In two years, I had done about 24 shows. If you are talking about experience, that is experience. I made many mistakes with sound, lighting, gating, and other things. I was learning on the job and became a ‘monster.’