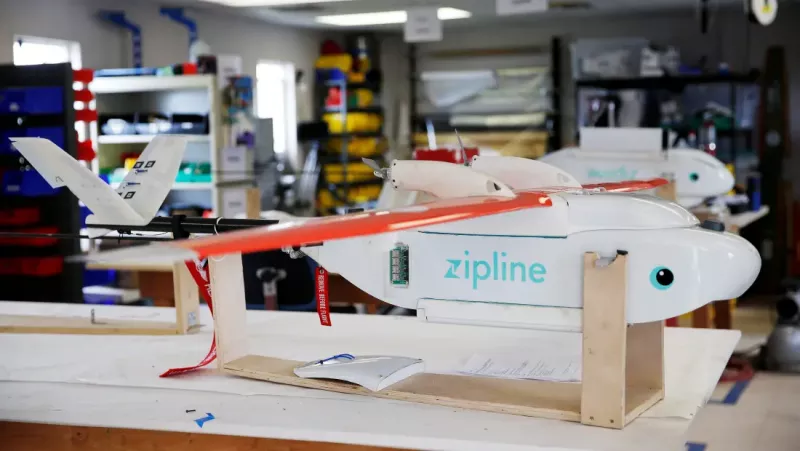

After operating for the past few years in Rwanda and Ghana, Zipline has opened its first distribution center in Nigeria today (June 3).

It is the first of three such centers the US-based logistics company plans to set up in Kaduna state, in northwest Nigeria. The center includes a small take-off and landing airspace for Zipline’s autonomous drones that will carry medicine, blood, and vaccines from a warehouse stocked by the ministry of health to local doctors and hospitals. The center, which will be staffed by 25 people and serve an 8,000 square mile area, plans to begin operations later this month.

“We are bringing instant logistics of essential medical products to one of the most challenging states logistically,” Daniel Marfo, the company’s senior vice president for Africa, told Quartz.

Zipline and Kaduna had set up the partnership before the company marked its fifth anniversary in Oct. 2021 with its 200,000th commercial delivery. But a new wave of insecurity in the state raises questions about the company’s strategy for success.

What is Zipline’s strategy?

Zipline’s expansion comes amidst increased drone delivery investments by US retail companies.

On May 24, Walmart said it will start delivering packages using drones to 4 million households in six US states at the cost of $3.99 per delivery. Amazon, FedEx, and UPS are multibillion-dollar logistics companies that are incorporating drone deliveries. Zipline has started to offer other types of services: In Rwanda, it now delivers products to farmers for artificial insemination of farm animals, Marfo said.

Still, the company’s immediate focus is on medical products. In Nigeria, it will prioritize locations that are difficult to navigate by road, kicking off in a state where attacks have made this type of travel challenging. In March, hundreds of passengers aboard a train ride from Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, were attacked by gunmen; at least eight passengers died, while some were abducted and still missing. This difficulty persists—this week, there were attacks on road passengers. While it is a lower scale of insecurity compared to the prevailing Boko Haram threat in the northeast, abduction and terrorism by gunmen is an ongoing menace in Kaduna and other parts of Nigeria.

“We’re aware of how difficult it is to transport medicines across Kaduna due to incidences of banditry, insecurity, and instability,” Marfo said. “To just move a few medical products from Kaduna city to the west of Kaduna, you need a military convoy. The [residents] there are really in a very difficult position.”

Zipline’s model is based on government contracts

Marfo said the difficulties will prove Zipline’s value, with the company finalizing deals to launch in other Nigerian states with different challenges: Bayelsa and Cross River, its next targets, are located next to rivers where residents risk abduction while traveling in boats.

Zipline did not disclose where its Kaduna distribution center is located, citing security concerns, and says its drones fly high enough to be out of sight from potential vandals.

“In the worst case scenario, when someone shoots one down, you cannot use it for anything,” Marfo said. The drones are programmed to go to exact locations and return to base after completing a delivery.

As in Rwanda and Ghana, Zipline has signed contracts with Kaduna state to transport the government’s stock of medical products to hospitals on-demand. Its first center will cover 500 health facilities. Two others to be built before next year’s first quarter will ensure deliveries to 95% of the state, Marfo said.

Zipline’s partnership with governments has been criticized for allowing these governments to outsource responsibility for providing basic public goods and services. Kaduna state seems to be using Zipline to paper over an endemic security problem. In 2017, the company charged between $15 and $45 per delivery; in Nigeria, it’s not clear how or if delivery fees will be passed on to consumers.

But Zipline can point to critical praise. A recent Lancet study of its Rwanda operations (pdf) between 2017 and 2019 found “faster delivery times and less blood component wastage in health facilities.”

“It’s not the easiest work, but the most necessary,” Marfo said.