A Portion Of The Paris Maison D'AMÉRIQUE LATINE Exhibition "MARRONNAGE: THE ART OF BREAKING ONE'S CHAINS" DEDICATES TO PHOTOGRAPHY BY YOUNG MAROON ARTISTS WHO ARE TAKING POSSESSION OF THEIR OWN HISTORY.

Slaves are escaping in every place they were forcibly brought to, no matter where you look. They go by the name Maroons. Through the Spanish word 'cimarrón', the name is derived from the French adjective ‘marron’. According to reports, they were marooned and it was considered a crime.

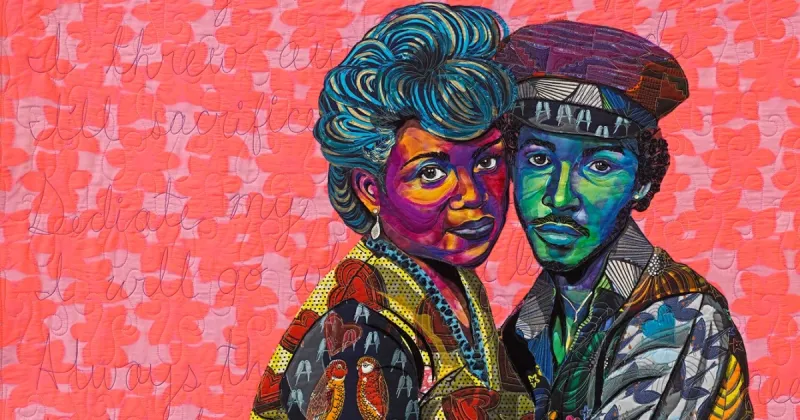

The Maroons are introduced by curators Thomas Mouzard and Geneviève Wiels. Six localities were gradually created by marronnage in mid-seventeenth century: Saamaka(saramaka), Dyuka, Paamaka, Boni/Aluku, Matawa, and Kwinti. The "Marronnage: The Art of Breaking One's Chains" exhibition at the Maison d'Amérique Latine focuses on the Maroon people and their descendants' creative development. For the first time, pieces gathered in the 1930s and currently housed at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac are confronted by various forms of contemporary artistic expression. The first ethnographic photographs by Pierre Verger and Jean Hurault are displayed in a section on photography with more modern images taken by young Maroon artists who appropriate their own past.

Karl Joseph

Karl Joseph, a 1973 Cayenne native, traveled to France for the first time as a student. He eagerly rediscovered Guyana eight years later, and he hasn't put down his camera since. He co-founded the Guyanese photography festival Rencontres photographiques in 2011 and splits his time between Cayenne and Sète. He serves as the festival's artistic director. “The Boni: this was the generic term used to describe brown people in my Creole childhood in Cayenne. Few people around me bothered with nuance when it came to knowing, and even less to understanding, these societies. We were probably too busy healing our own wounds—colonisation oblige; probably too busy trying to assimilate—France oblige. My first experience of this ‘other country,’ as I have long called it, was in 2001. With two friends, we had decided to go up the Maroni River as far as we could. … This ‘other country” thus unfolded before me to the rhythm of landscapes passed in a boat with a perilous waterline. With each jump, the wood of the hull creaked and warped. We prayed to stay afloat and looked into the face and the eyes of our Maroon “boatswain” who took in every ripple on the water’s surface with calm intent, letting us know he could read the river and that once again we would skip over the rocks. During those few days, I watched from our pirogue the luminous, ephemeral traces of a hidden Guyana. That Guyana has its own languages, its own architecture, its own codes, its own history: it is one and yet divisible. I knew that I would return, and, a stranger in my own native land, I have returned often to satisfy my greatest pleasure, that of meeting the other, my other self.”

Ramon Ngwete

Ramon Ngwete was born in 1992 in Kourou, where he was raised in a Saamaka settlement, and at the age of twenty he started his profession as a self-taught photographer. “I started photographing after having drawn for a long time. At school, I was not very good at reading, and I learned to read from comic books. They taught me to love images. I grew up and lived in the Saamaka village of Kourou, until it burned down in 2004. We had a small wooden house, I slept in a hammock. We didn’t have to lock the door, life was peaceful and happy, even though we were poor. During the rainy season, the shanty town would get flooded. With friends, we used to transport journalists in the hulls of refrigerators that we used like dugouts. … I would love to have owned a camera at that age, to capture those moments, the wooden houses, the neighborhood, the women together, the homemade meals, the celebrations, what life was like. … The photos presented here were taken in the Saamaka country, in Surinam. There they grow manioc and women wash their clothes by the river… It is beautiful to see that people still live like that today. And at the same time, they have adapted to the modern world. I won’t lie to you, my grandmother has a phone, she uses WhatsApp. A cousin asked me recently: ‘Hey, Ramon, have you seen that series on Netflix?’ While in Guyana we launch rockets, inland communes have connection problems! I want to do a project about the Saamaka people. We tend to say that ‘the white man came to do a reportage and said a lot of nonsense.’ Rather than complaining, all we had to do was to make sure he was well-informed and show him around. Better yet, if we don’t want outsiders to come and tell our story, we should do it ourselves!”