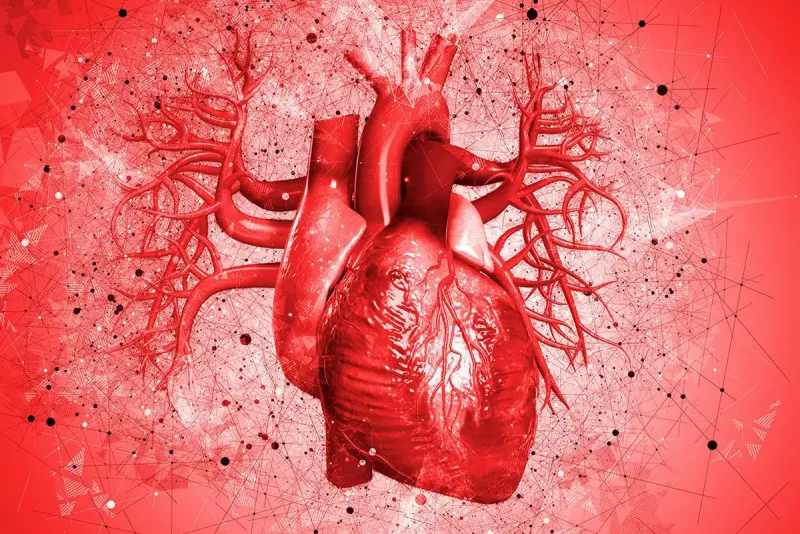

A new research venture could bring about a cure for genetic heart conditions.

The global team of experts assembled for this project expects to have the gene therapy ready to start testing in clinical trials in the next five years.

The new gene therapy could lead to cures for an abundance of other genetic diseases.

The world’s first-ever cure for genetic heart conditions seems to be within reach.

Read Also: Samsung’s new foldables arrives August 26

A global team of experts from the U.K., U.S., and Singapore is joining forces for the CureHeart Project to develop effective genetic therapies for cardiomyopathies, or diseases of the heart muscle that make it harder for the heart to pump blood to the rest of the body. This venture is expected to cure countless afflicted people after the team was recently awarded an approximate $37 million grant from the British Heart Foundation to go towards life-saving research.

Researchers will use precision genetic techniques, called base and prime editing, in the heart for the first time to design and test the first cure for inherited heart muscle diseases, with the aim of turning off faulty genes (so that they are no longer expressing the harmful mutations). While researchers have yet to reach human trials, the treatment is promising, having already seen success in animal trials.

“For decades, we’ve hoped that we could cure heart conditions. Most cardiac conditions are not curable right now, but just manageable,” Richard Wright, M.D., Cardiologist at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, CA, tells Prevention. “At least for this unusual array of disease states where a specific gene is abnormal and we’ve been able to identify it, there’s the possible opportunity, in theory, that we could go right into the cell and fix the fundamental problem in these people and cure them.”

All those with inherited heart muscle conditions, also known as genetic cardiomyopathies, have a 50/50 risk of passing faulty genes on to each of their children. And, often, several members of the same family develop heart failure, need a heart transplant, or die at a young age. Professor Hugh Watkins, from the University of Oxford and lead investigator of the CureHeart project, told The Guardian that cardiomyopathies were “really common” and affected one person in every 250 around the world.

“This is our once-in-generation opportunity to relieve families of the constant worry of sudden death, heart failure and potential need for a heart transplant,” Watkins told The Guardian. “After 30 years of research, we have discovered many of the genes and specific genetic faults responsible for different cardiomyopathies, and how they work. We believe that we will have a gene therapy ready to start testing in clinical trials in the next five years.”

About half of the genes that we have are turned on to make proteins in the heart, and there are thousands of mistakes in the genetic code that lead to the heart being too weak or heart muscle being too thick, which can lead to a myriad of health issues. These mutations are one of the more common causes of heart failure, says Dr. Wright. “If this treatment were successful, you could rather quickly re-program the genes to make normal, instead of abnormal, proteins within the heart, leading to the heart reversing its dysfunction and going back to normal.”

If you inherit a “bad” gene, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll end up with the disease. Some people carry these mutations, or “bad genes,” their whole lives and never manifest any disease. However, in some specific cases, we know for certain that a disease will eventually manifest itself later in life—in which case, we may want to prevent it from ever happening. It’s possible that this cure could be distributed to those with cardiomyopathies at any time in their lives, before or after the condition presents itself.

The bottom line

This ground-breaking research could mean a cure for not only heart conditions but many other genetic diseases, too. “Genetic blood disorders, such as sickle cell anemia, or brain disorders such as Huntington’s or chorea—these are diseases where we’ve known what the problem is but we just haven’t had the tools to correct the problem,” says Dr. Wright.

So how do you go into a cell and correct the genetic code without potentially causing more harm? Scientists used to use viruses to carry information into the cell, which obviously has its potential side effects, but now they have the ability to do it directly and cut out the carrier entirely, which may prove to be much safer, according to Dr. Wright.

But, there are still many aspects of this treatment to be considered, if and when the cure becomes readily available. Though the research team consists of some of the top scientists across the globe, there’s still much to be done. Dr. Wright says that now, “they just finally have arrows in their quiver that they can use to attack this problem.”