Revered for his textiles, his art and his socialism, William Morris is the celebrated leader of the Arts and Crafts movement, a renowned intellectual who revolutionised decorative art and design in Britain. His wife, Jane, meanwhile, has been relegated to the status of a silent muse.

Now, the first joint biography of the couple will shine a light on their personal and creative partnership, and reassert the rightful place of Jane Morris – a skilled embroiderer and talented designer – in the history books.

“Jane’s work has been undervalued and generally ignored,” said Suzanne Fagence Cooper, author of the forthcoming biography, How We Might Live. “She is seen as just a face and not as a maker with her own ideas.”

Immortalised for ever in the pre-Raphaelite paintings of her obsessive lover Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Jane Morris was essential to the creation and success of her husband’s decorative arts firm, Morris & Co, in 1861, the book will explain.

“They needed her soft skills and her embroidery skills, and her willingness to be the pre-Raphaelite face of the Morris company brand,” Fagence Cooper said.

Jane’s artistic contributions have been ignored, Cooper thinks, in part because she was such a famous beauty, who was notoriously unfaithful to her husband with his friend Rossetti and others. “I think there’s been some prurience around that. It has made her a more complicated figure,” she said.

As the working-class daughter of an ostler and a laundress, Jane had no formal education and has been viewed as undeserving – and unequal to – her wealthy, middle-class genius of a husband: “People want to put William Morris on a pedestal,” said Dr Johanna Amos, of Queen’s University in Ontario. “There’s this view of Jane as someone who betrayed this lion of the British art scene in the 19th century. And I think that damaged her reputation.”

But without Jane’s housekeeping and networking skills, Morris & Co might not have been formed, said Fagence Cooper: “It was set up, basically, around her dining table at Red House in Kent.”

One of the first decorations that William Morris made was a daisy-patterned wall hanging for Red House, which has since cemented his reputation as a design pioneer. “Jane later tells her daughter May, in a letter, that she chose the fabrics for that. And she and Morris sat down together, worked out what pattern was possible and then they stitched it together,” said Cooper.

The couple invited their artist friends, who included Edward Burne-Jones and Rossetti, to help them finish the decoration of Red House – and when the first discussions about Morris & Co took place between the men, it is likely that Jane was present, and involved, Fagence Cooper thinks. “They were designing for Red House, and the first designs happened there. But then they decided to make it bigger and to start to sell those designs,” she said.

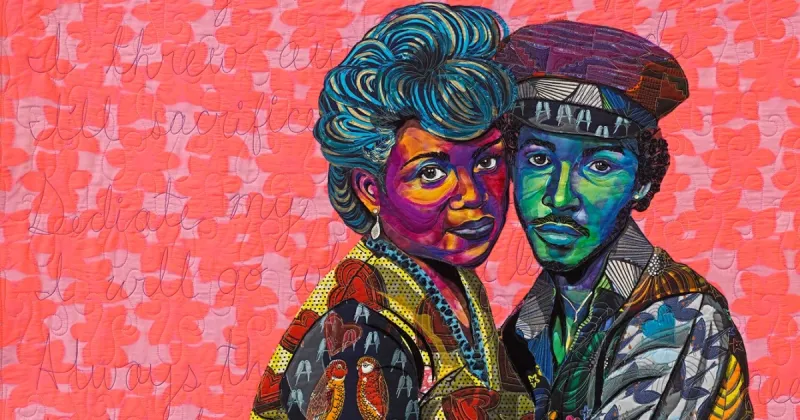

Jane Morris with her daughter May around 1865

In particular, she thinks that Jane would have put forward ideas about the embroidery they could sell. “She was involved in getting the materials, and choosing the right fabric, embroidery threads and silks. She’s absolutely essential to the making of the products, as well as the gathering of people to begin the process of founding Morris & Co.”

For more than 20 years, she then ran the embroidery side of the business which, Fagence Cooper said, became “very significant”.

“She would be stitching, and overseeing stitching for all the women, as they turned the men’s designs into beautiful hangings and decorations,” she added.

Amos said: “She probably made choices around colour, around the selection of stitches, around how the work took shape.” But her skill in being able to make those decisions and to interpret her husband’s ideas has not, traditionally, been recognised as creative “design” work.

Because all Jane’s labour was unpaid and, unlike her male co-founders, she had no money to invest in the company, her name doesn’t appear in the company accounts. It was only in 2012, when Jane’s letters were discovered and published, that her “invisible” work on Morris & Co designs became known to academics, Fagence Cooper said.

The biography, which is published on on 9 June, will also demonstrate that Jane was involved in Rossetti’s artistic process when she sat for The Blue Silk Dress, his painting of her, in 1868.

William Morris’s ‘heavenJane herself made the dress in which she sat, said Fagence Cooper, “and there was a lot of to-ing and fro-ing in the letters between her and Rossetti about what it should look like, how it should feel. And Rossetti really bows to her expertise.”

But it is only in the little “keepsake books” she made for friends that Jane has the opportunity to display her own “really distinctive” designs, said Fagence Cooper. “They’re very geometric and rely a lot on red and black contrasts, and all the backgrounds are shaded with little lines, which are almost like embroidery stitches.

“They look much more like Vanessa Bell’s work – they have an early Bloomsbury feel. It’s very different from what William Morris was making.”