Think about Marilyn Monroe, and certain images instantly come to mind: the red lips, slightly parted; the sleepy, siren eyes; the platinum blonde hair; and that voice, breathy, like she just woke up and can't wait for you to join her in bed. Her friend, the writer Truman Capote, described her as a "platinum sex-explosion". The cinematographer Leon Shamroy, who shot her very first screen test in 1946, famously said she was like "sex on a piece of film". Marilyn conjures up sex and – simultaneously – misery, thanks to the way her troubled personal life has been pored over from the moment she became a movie star. Since her death from a barbiturate overdose in 1962, the elements that made Marilyn Monroe into an icon have also led people to dehumanize her, over and over again.

And with the latest biopic of the movie star, Andrew Dominik's adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates' 2000 novel Blonde, her legacy has once again been debased.

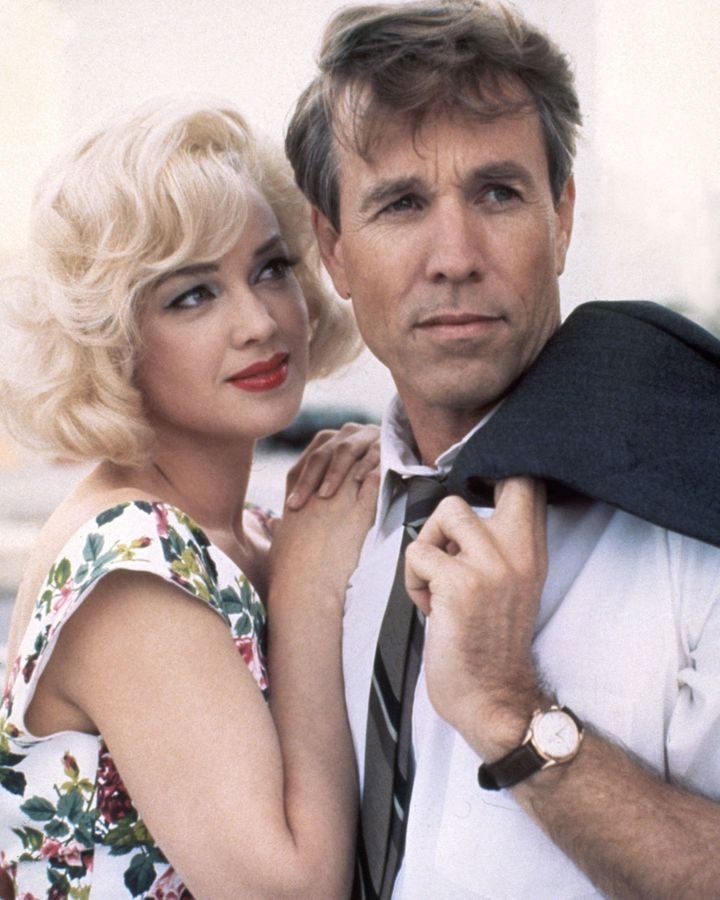

Oates' Pulitzer Prize-winning book is a fictionalization of Marilyn's life, narrated from the point of view of a deeply traumatized and lonely woman, in love with movies and the idea of love, but desperately crippled with daddy issues that infect every single relationship she develops. Dominik's is not the first Blonde screen adaptation – that was Joyce Chopra's 2001 TV movie, which starred Poppy Montgomery. Chopra's version channels the cruelty of Marilyn's life without displaying the surgical coldness of Dominik's film. With each character speaking directly to the camera, verbalizing their point-of-view as the scenes unfold, it's a less exploitative adaptation and a more psychoanalytical one. Both Marilyn and the men she was close to get to have their say.

Montgomery plays Marilyn as an overly grateful and naive woman-child, saying please and thank you to the very men who dismiss and debase her. "Let's drop the goo-goo routine, you can't be as dumb as you look", the studio head known as Mr R (an avatar for 20th Century Fox boss Darryl F Zanuck) tells her just before he sexually assaults her. However there is, at least, an element of bratty joyfulness to this Marilyn as she enjoys her success, and the film ends without putting her (and us) through her sorrowful demise.

She stands for different narratives: the victim narrative, and the absolute essence of feminine, sexual glamour and irresistibility – Dr Lucy Bolton

Dominik turns Marilyn's story into a body horror. As Dr Lucy Bolton, a reader in film studies at Queen Mary University of London, says, the actress was often "cut up into segments in her films," with shots that focused on her breasts, her crotch, her mouth. "It's objectification, it's fetishisation, it's ownership. It's classic Laura Mulvey stuff," she says, referring to the pioneering academic's "male gaze" theory. During her lifetime and beyond, Marilyn's body has been "used to sell a dream of desirability", posits Yhara Zayd in her video essay Selling Marilyn: A Life Merchandised, about the posthumous commercial exploitation of Monroe's image.

In Blonde, Dominik fixates on Marilyn's body to a gynecological extent. She is not merely objectified (the first shot we see of her is her backside during the shoot of The Seven Year Itch), she is prodded, examined, raped, subjected to two forced abortions, and abused physically and emotionally. Blonde seems intent on destroying Marilyn Monroe, the woman, and perverting the image of her by showing us none of the talent, ambition or pride in her work. Almost every moment shown is agonizing, and Ana de Armas (who plays Marilyn) weeps almost constantly throughout the film's two hour and 45 minute runtime. It's torture porn with a lick of Hollywood gloss.

The same old story

"Please don't make me into a joke," Marilyn said, to an unnamed interviewer near the end of her life. But Hollywood's cruel joke has been to turn her into a train wreck, reducing her legacy to a series of messy love affairs, daddy issues and addiction. Big-screen and TV biopics have tried to explain her many times over, but they always come back to the same narrative – that of a victim, a tragic beauty. Is there really nothing else worth saying about Marilyn and her cinematic legacy?

A whole host of made-for-TV biopics like 1993's Marilyn and Bobby: The Final Affair have portrayed Marilyn in demeaning terms (Credit: Alamy)

According to Bolton, our enduring fascination with Marilyn Monroe is rooted in how easily she can be moulded to fit different stories: "She stands for different narratives: the victim narrative, and the absolute essence of feminine, sexual glamour and irresistibility, in her own lifetime and in retrospect. She's a pin-up as well as an actress, and a comedian. People relate to her as someone struggling and trying very hard to be taken seriously as a dramatic actress." She has been portrayed as a bimbo, a dummy, a diva and a tragedy case. Her shortcomings are often uttered in the same breath as her accomplishments, as though to diminish her charm and talent.

There is also a mystery to Marilyn, something elusive that can lead to indulgence on the part of shallow filmmakers. In the many films and limited series that have dramatised her life, most focus on her rags-to-riches story, and skip quickly to her demise, her difficult persona on set and her troubles with men of note, from her marriages to Joe DiMaggio and Arthur Miller to her affairs with the Kennedy brothers, John and Bobby. By focusing on the tragedies of her life and exaggerating the abuses she suffered, these biopics continue to disempower her, decades after her death. "There's a removal of power from her [as] if she is a victim-child, who became a victim-adult, who died a victim," says Bolton. "It undermines her abilities if we only talk about the beginning and the end. [It suggests] the impossibility of her living."

There is something in the most puritanical part of our nature that says, these people, these Hollywood people, they have so much and they deserve it so little – Farran Smith Nehme

Marilyn Monroe's life was one of extreme lows and extraordinary highs. Born Norma Jean Baker to a single, mentally ill mother who was unfit to take care of her, she was put in an orphanage and foster homes until she was emancipated by marriage. She became an actress after she was already a successful pin-up model. Marilyn's mystery is not that of her ascent, but of the extreme contradictions of her life. She was a generational talent, a movie star with undeniable charisma, charm, fantastic comedic timing and an aggressive earnestness about her that was as disarming as it was captivating. Watching her on screen, even today, is to fall under the spell of cinema. She belongs to, and at times feels created entirely for, the screen. Meanwhile, the contrast between her carefree on-screen persona and her supposedly tortured off-screen existence has become the alluring core of her narrative: the woman-girl, the success-tragedy, the self-loathing-beauty, the unlovable romantic. Her untimely death remains a favourite for conspiracy theories that most often include the Kennedys and the FBI, and which Blonde, both book and film, indulge in. "People find it hard to reconcile that someone can be so exceptional and meet such a banal end," says Bolton.

But why the endless drive to tear her down, to reduce her to a sad cautionary tale? "There is something in the most puritanical part of our nature that says, these people, these Hollywood people, they have so much and they deserve it so little," the writer and film critic Farran Smith Nehme tells BBC Culture – and so because Marilyn was the biggest star of them all, it's as if she deserves these, in Nehme's words, "relentlessly downbeat" interpretations of her life. In the wave of made-for-TV Marilyn biopics of the 1980s and 90s, as well as the TV series about other Hollywood glitterati (The Mystery of Natalie Wood [2004], The Rat Pack [1998]) or the Kennedys (Marilyn & Bobby: Her Final Affair [1993], The Kennedys [2011]) in which she features, Marilyn is presented at best as a hot mess and, at worst, as a wanton floozy. These films see her only as tragic, or completely disposable.

The Two Marilyns

Every single biopic made of her life zeroes in on the tension between Norma Jean Baker and Marilyn Monroe, the woman and the movie star. Some take this approach very literally, by casting two different actresses to play the roles, literally separating the women. The very first person to do this was the self-proclaimed "schlockmeister" Larry Buchanan, with his double bill of biopics: in Goodbye, Norma Jean (1976), Misty Rowe plays the title role, ending the film with her transformation into the blonde bombshell; and, in the follow-up, Goodnight, Sweet Marilyn (1989), noted Monroe impersonator Paula Lane plays Marilyn.