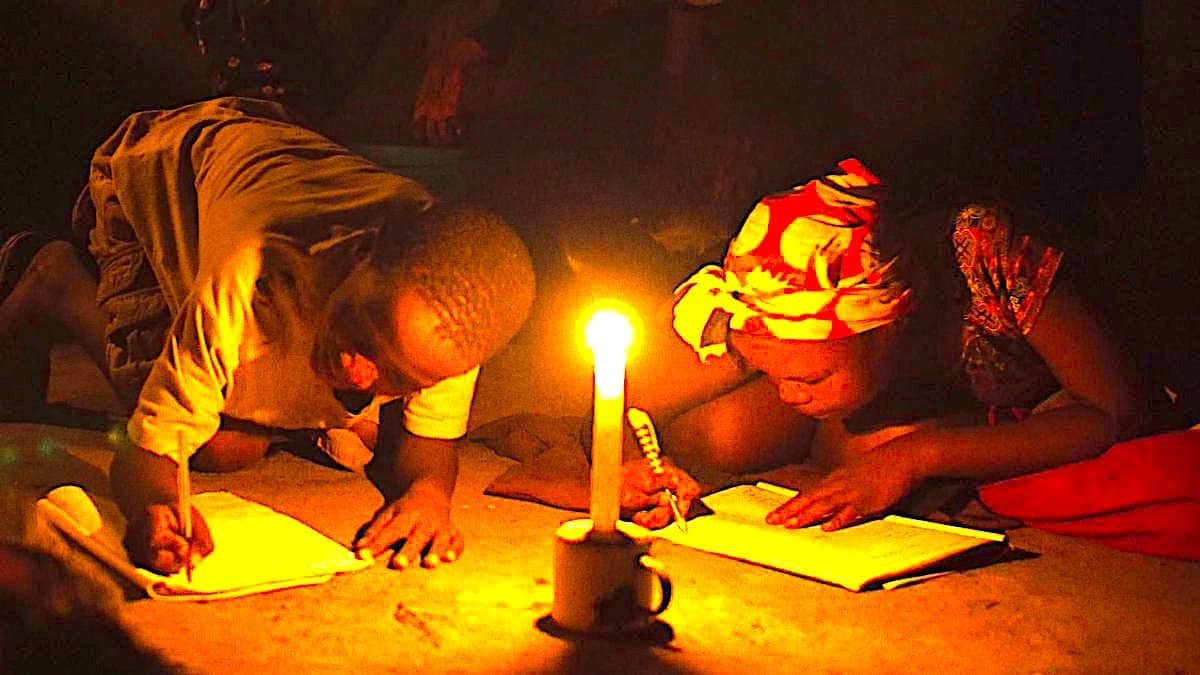

Africa is facing a profound paradox: it is the continent with the most sunshine hours and vast natural wealth, yet it is home to approximately 80% of the global population without electricity. This startling imbalance, highlighted by Bloomberg Originals, underscores why this lack of power is not just an inconvenience but a fundamental barrier to economic independence, health, education, and, critically, industrialization. As virtually every wealthy nation, from the UK and the US to Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea, achieved prosperity through industrialization fueled by abundant power, Africa finds itself stalled at the starting line of its own industrial revolution.

Bloomberg Originals reveals that the lack of electricity consumption directly correlates with lower GDP growth. To achieve economic "take off," a country typically requires 1,000 to 2,000 kilowatt-hours of energy per person annually, but many African countries currently sit at less than 200 kilowatt-hours. Despite this shortfall, calling Africa "energy poor" is a mischaracterization. The continent is richly endowed, possessing about 30% of the world's minerals, approximately 10% of global crude and gas, and enormous untapped potential in hydropower and solar energy. Furthermore, Africa's substantial labor force of a billion and a half people, with a median age of 19, represents a "giant young workforce to power the future".

The challenge lies in infrastructure and investment. In populous countries like Nigeria, the lack of sufficient power generation and distribution has forced manufacturers to essentially abandon the national grid. Large companies, such as Beta Glass (which produces packaging for Budweiser and Coca-Cola), have been compelled to use expensive backup solutions, including liquefied natural gas delivered by tanker and roof-mounted solar power plants. However, these are luxuries that only large firms can afford. Smaller businesses rely on diesel power generators, an option that is both expensive and fundamentally insufficient for mass industrialization. Because diesel generators make production uncompetitive, African industry accounts for just 1% of global manufactured exports.

Related article - Uphorial Shopify

Investment, particularly from the commercial sector, is hindered by significant hurdles, including huge sunk costs and long payment schedules. Political risk and corruption are major inhibitors, making it tough for investors to adhere to Western compliance rules. Investors worry that contracts signed under one administration may not be honored by the next, creating major concerns regarding governance and political stability. Compounding this difficulty, loans to African countries often come with unjustifiably high interest rates, far exceeding those charged to countries with similar debt-to-GDP ratios.

Despite these formidable obstacles, some African nations are forging their own path to energy security. Ethiopia, for example, is constructing the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa's largest hydroelectric-powered dam, a project that began in 2011 and is seen as a huge achievement. The dam has become a nationalist project, funded in part by crowdsourcing, with citizens donating money and buying domestic bonds, driven by deep pride. This demonstrates Africans "taking energy security into their own hands".

Another strategy is the rapid adoption of green technology. Africa boasts some of the world's best potential solar sites. The demand is evidenced by the import of about 15 gigawatts of solar panels in the 12 months leading up to June, often from China, which is particularly transformational for rural areas beyond the reach of national grids. The development of mini-grids—small, often renewable power plants that can power a neighborhood or industrial estate—is also emerging as a solution, creating a positive multiplier effect by allowing other businesses to emerge in agricultural communities. The World Bank has launched an initiative to connect 300 million Africans to power by 2030, but this comes with the caveat that countries must choose the lowest cost solutions, which are almost always renewable.

However, the international policy push to prioritize green energy is a contentious point, making it difficult for African nations to secure funding for essential fossil fuel projects. Many African leaders are "irked" by the restrictions placed on future emissions, arguing that this policy is unfair and not conducive to a just transition. The widely held view that Western countries got rich by burning fossil fuels, but Africa should forgo that option, is considered by many to be "condescending and hypocritical".

Ultimately, African policy makers agree that whether it is achieved through green energy or fossil fuels, electrification "needs to happen". As Bloomberg Originals concludes, solving Africa's energy insecurity is a global imperative. An energy-secure Africa would create jobs and hope for the future, making young African citizens less likely to want to leave. With a massive young population and no corresponding manufacturing sector to absorb them, it is "in the interest of everyone around the world that the last continent that hasn't gone through an industrial revolution does".