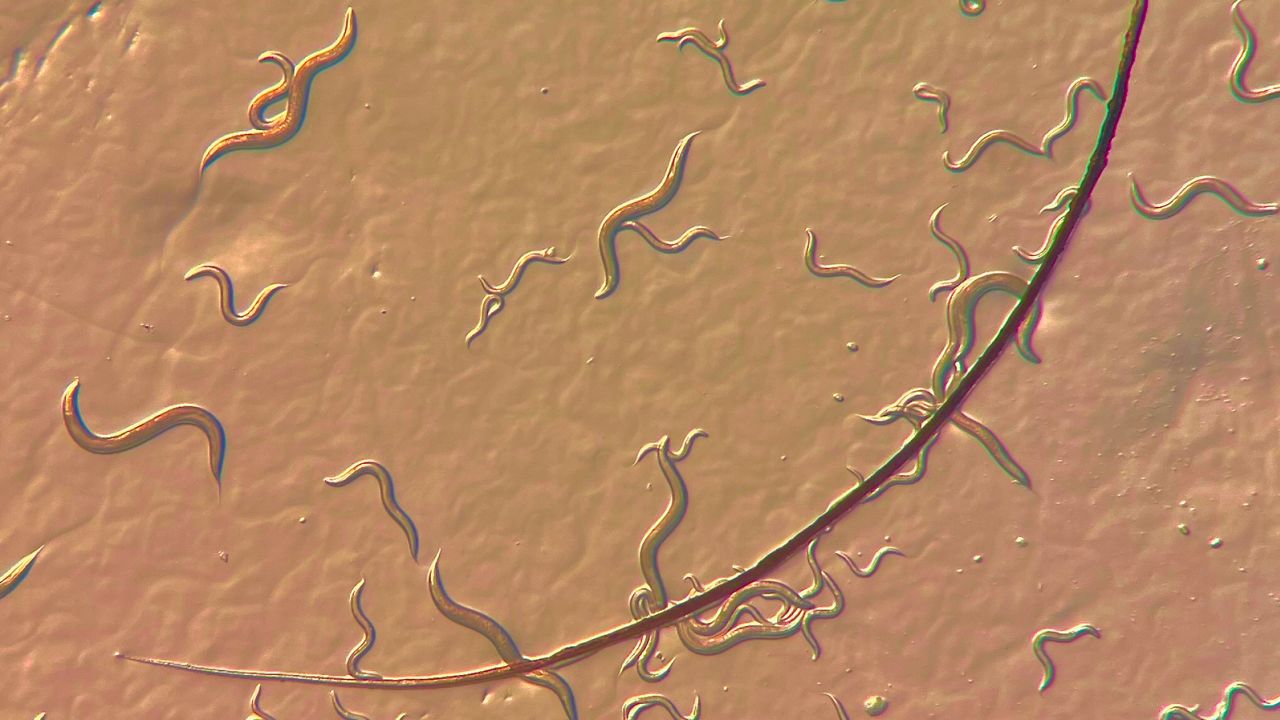

One Friday afternoon, not long after Oregon made cannabis legal in 2015, some lab researchers in the state embarked on a quirky experiment. The team worked with a type of tiny nematode worm called Caenorhabditis elegans, smaller than a human eyelash, to understand its food preferences and, on a whim, decided to soak the worms in cannabinoids — the active substances found in weed. It turned out the worms did respond, and cannabinoids made them hungrier for their favored foods and less hungry for their non-favored food. The research ultimately revealed that the worms, like humans, engage in hedonic feeding — a phenomenon more commonly known as the munchies.

Read Also: How coffee and tea can affect risk of early death for adults with diabetes - New Study

“The very fact of hedonic feeding in nematodes was surprising. The munchies in a worm. Really?” said Shawn Lockery, a professor at the Institute of Neuroscience at the University of Oregon in Eugene and coauthor of a study that was published Thursday in the scientific journal Current Biology. Previously cannabinoids were only known to affect humans and other mammals — making them want to eat more and crave the tastiest, most high-calorie foods.

The worms, however, weren’t tearing through a pile of junk food. They fed on different types of bacteria.

Fluorescent worms

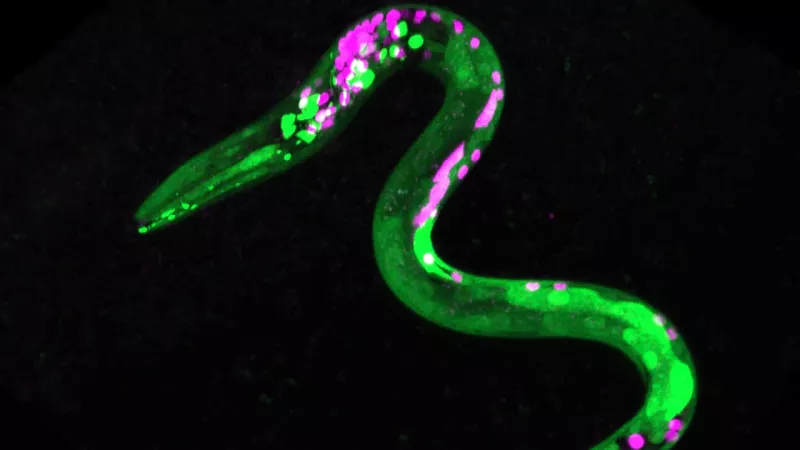

By measuring the swallowing rate of the worms, Lockery and his team determined that the cannabinoids were increasing how much of a particular bacteria blend the worms ate, making them hungrier. They showed the worms craved the food they found more palatable by putting them in a T-shaped maze that was baited with a preferred bacteria blend and less preferred food. The worms were also genetically engineered so that certain neurons and muscles glowed fluorescent, with green dots showing neurons that respond to cannabinoids.

Lockery added that the active ingredients in cannabis caused the worms’ “olfactory neurons to be more sensitive to preferred food and less sensitive to less preferred food,” but why this happened was “quite a mystery” so he planned to follow up on it. In humans and other animals, cannabinoids act by binding to cannabinoid receptors in the brain, nervous system, and other parts of the body, Lockery said. Those receptors normally respond to related molecules that are naturally present in the body, known as endocannabinoids. The endocannabinoid system plays important roles in eating, anxiety, learning and memory, reproduction, and metabolism. At the molecular level, the cannabinoid system in these worms looks a lot like that in people and other animals.

“Our findings help us to understand more fully our place in the animal universe,” Lockery said via email. “It shows that in at least one respect, the decisions we make are influenced by factors that even a worm can understand.”

Ideal lab animal

C. elegans is an ideal lab animal for studying nerve cells. Despite having a small number of neurons (302 neurons versus 86 billion neurons in humans), the worms have a nervous system that includes a primitive brain. It was also the first animal to have its genome sequenced back in 1998. Lockery said the research had the potential to accelerate the discovery of new medications for metabolic disorders, including obesity. “Drug discovery often begins with gene discovery, and C. elegans is a premier organism for this,” he said. “Genetic research in C. elegans is fast and inexpensive. … Our demonstration that the human cannabinoid receptor is functional in regulating the worm munchies emphasizes the deep parallels between humans and worms in regulating metabolism.” What the research really shows though is that a “wait, what?” moment on a Friday afternoon can be of scientific value. “We felt that a positive result would (be) both amusing and thought-provoking for the general public. The science that first makes you laugh, then makes you think,” Lockery said.