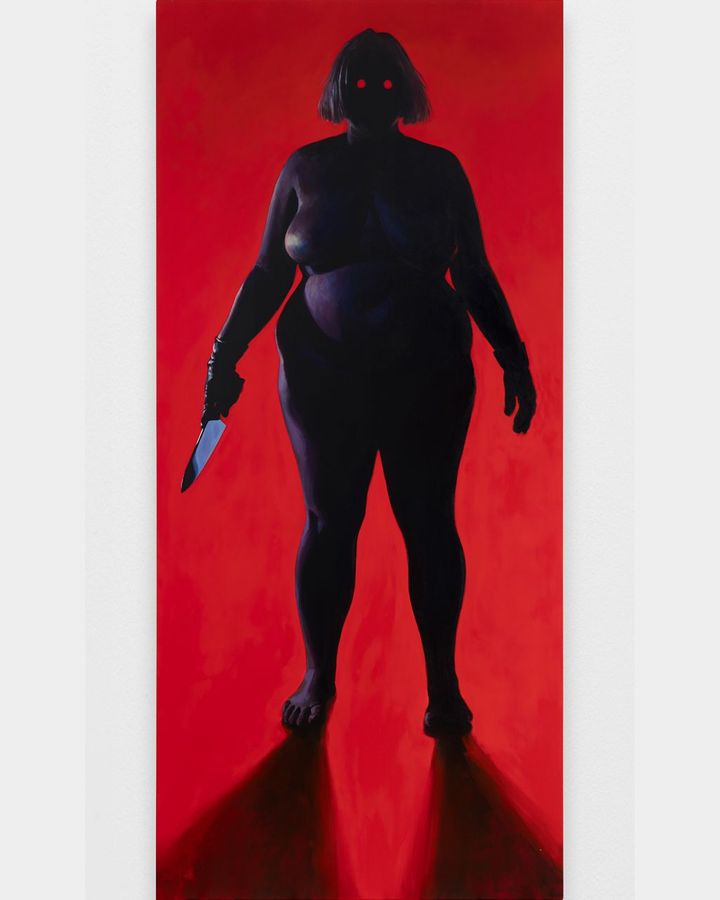

Horror films and stories confront us with the darkest parts of life. For the visual artists who use them in their work, horror tropes can provide a route to healing and empowerment. Some subvert culturally entrenched clichés, such as stigmatized female bleeding and demonized witchcraft. For others, the horror of lived experience is conveyed through grotesque imagery. "Horror has given me the strength and language to discuss trauma and things I'm ashamed of in a way that distances me from them," says Lydia Pettit. The London-based artist has just opened a solo exhibition, In Your Anger, I See Fear at Berlin's Galerie Judin, in which she inhabits the roles of terrorized victim, knife-wielding killer, and formidable witch. She confronts sexual trauma and PTSD through painting, addressing not just the victimized parts of herself, but also her sense of vengeance.

"The villain character in my work is about me giving my anger and pain this extremely powerful, monolithic presence so it can live outside my body," she says. "Painting myself as a naked, knife-wielding monster is a way to confront the reality I'm living with; the ramifications of swallowing my trauma and trying to appease people all my life. Putting that entity on canvas and confronting it, while also knowing it's me, is a great way to process and take back control." Horror can offer a nuanced visualization of the psyche. Analyst and author Lisa Marchiano co-host This Jungian Life podcast, which delves into themes such as beauty and sex through psychoanalysis and storytelling. "Carl Jung talked about 'the shadow', and there are many manifestations of it," she says. "It might be parts of ourselves that aren't allowed, or parts that are evil that we have to contend with.

A lot of horror films show us triumphing over evil, which might be an image of the ego contending with these parts of the psyche." A horror-themed episode of the podcast addresses the role of the monster within such narratives. "There's an incredible song, Weeping, by Dan Heymann," she tells BBC Culture. "It's about this monster that's locked up and intimidated; people come to look at it. When everything goes quiet you realize that the monster isn't roaring, it's weeping. It's about apartheid, where a group of people were othered and made to be the monster. Viewed from a psychological angle, monsters could be seen as parts of ourselves that we've disowned. That part of us is often where our pain is that wants to be known, integrated, and loved." Six contemporary artists share how they embrace or subvert deep-rooted ideas of the monstrous within their work.

Marianna Simnett reveals the wicked parts of the mind that many experiences from childhood but few acknowledge. Her films evoke the "subtle undercurrents that are always simmering beneath the surface of our daily existence," she says. "We're all culpable of enacting violence on others." Films such as The Bird Game and Confessions of a Crow employ the conventions of twisted children's tales, with paranormal animals and young actors. "I think the problem with our Western conception of children is that they are pure and innocent and don't have any dark feelings." Simnett candidly rejects the constrictive expectation of childhood innocence that gives rise to guilt and shame, and in doing so creates space for all parts of the mind to exist. Simnett combines uneasy terror with humor, fetish, and hybridity. While her works often transport viewers to imagined spaces, they capture the vulnerability that many feel now. "We're living in a very psychologically taxing time where our world is full of major contradictions and paradoxes," she says. "Horror as a genre is able to express the fragility that one feels in one's body when the external world is at the brink of collapse."

Grace Ndiritu

While shamanism has long been negatively connected with witchcraft and stereotyped in Western culture, Grace Ndiritu celebrates its potential for healing. "Shamanism has historically been feared because Western thinking sees the world as dead, not animistic," she says. "If you don't believe in anything that can't be scientifically proven or rationally thought about, these things need to be feared. Most indigenous cultures and a large percentage of the non-Western world believe in something that is other. The power of the natural world is particularly important in terms of healing." Ndiritu has, since 2012, explored the role of shamanic and non-rational methodologies in gallery spaces through her series Healing the Museum. The project is now showing at SMAK in Ghent. Working with performance and inclusive activities, the artist aims to reactivate the sacredness of cultural spaces and leads groups on healing trauma. "It's taken 20 years for this practice to really be taken seriously," she says. "When I began the project, I felt museums were dying and the only way to heal them was to bring new energies into them."

Jenkin van Zyl

Working across film and immersive installation, Jenkin van Zyl unites horror, fetish, and club culture. His subversive works full of monstrous creatures and narratives of self-destruction contrast with 21st-Century capitalism and its expectations of conformity.

"Horror is exciting because it sees the potential of marginality to be a source of power," he tells BBC Culture. "I often create spaces that relish the idea of collapse, entropy, or ruin as the potential for countering global politics. In a culture that puts so much violence on non-conforming or gender-queer bodies, I'm interested in creating spaces where unruly bodies not only survive but flourish." A recent exhibition at Edel Assanti in London saw Van Zyl erect a "love hotel" that housed a looped film, in which rat characters engaged in a relentless dance contest. Cyclical ruination often features in the artist's works, defying the industrial myth of progress. "It's the idea of bodies that can go through trauma or collapse but then also regenerate," he says. "I'm presenting things that may be seen as monstrous and horrific as glamourous and sexy, and things traditionally seen as beautiful as alienated and useless."

Hayv Kahraman

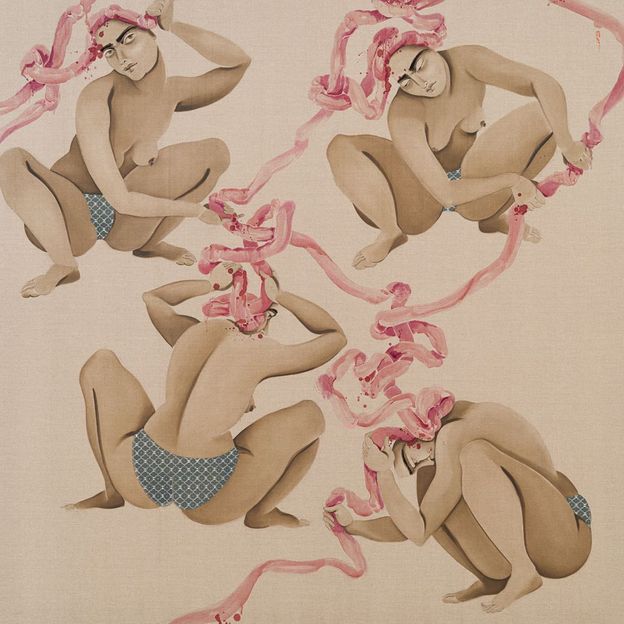

Hayv Kahraman's intricate paintings reclaim the horror of her experience of immigration. She depicts women bent to extreme angles, showing the body as a site of both violence and self-possession. "When one is subjugated, dehumanized and completely robbed of any juridical rights, the body is the last site in which one has autonomy," she says. "The body for me is a site of resistance and re-existence. It's a vehicle to question and rework the various injustices that have plagued it and pinned it down."

While her women assume excruciating poses, they have undeniable strength, sometimes directly watching the viewer who gazes upon their tangled forms. "The 'looking back' is a confrontation… They are saying, 'I know how I'm seen and I'm here to challenge that.' I always think about [WEB] Du Bois's 'double consciousness', where he speaks about the sensation of looking at yourself through the eyes of the other. In this case the other is the dominant white heteronormative society."

In her most visceral works, knotted guts tumble from open mouths and torsos. "As somebody who has felt dehumanised, and lived through the trauma of assimilation, which mostly involves the erasure of oneself, the instinctual or the gut feeling is something that needs to be repaired," she says. "I wanted to reconnect and regain my gut feelings."