Pioneers at Paris’s Musée du Luxembourg places a particular emphasis on women artists who challenged and subverted conventional norms of gender presentation, sexuality, motherhood, and race.

War in Europe, a global pandemic, and rapid technological change that altered people’s relationships to work, family, and society. This is the backdrop against which the art historical exhibition Pioneers at the Musée du Luxembourg aims to rewrite the roles that women played in the city’s avant-garde art movements of the 1920s. Featuring works in various mediums by more than 45 artists, the exhibition places a particular emphasis on women who — through painting, sculpture, music, dance, and writing — challenged and subverted conventional norms of gender presentation, sexuality, motherhood, and race.

The show’s lead curator, Camille Morineau, is a pioneer in the French art world in her own right. She’s the director of AWARE (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions), a nonprofit she founded in 2014 to “rewrite the history of art” by placing “women on the same level as their male counterparts.”

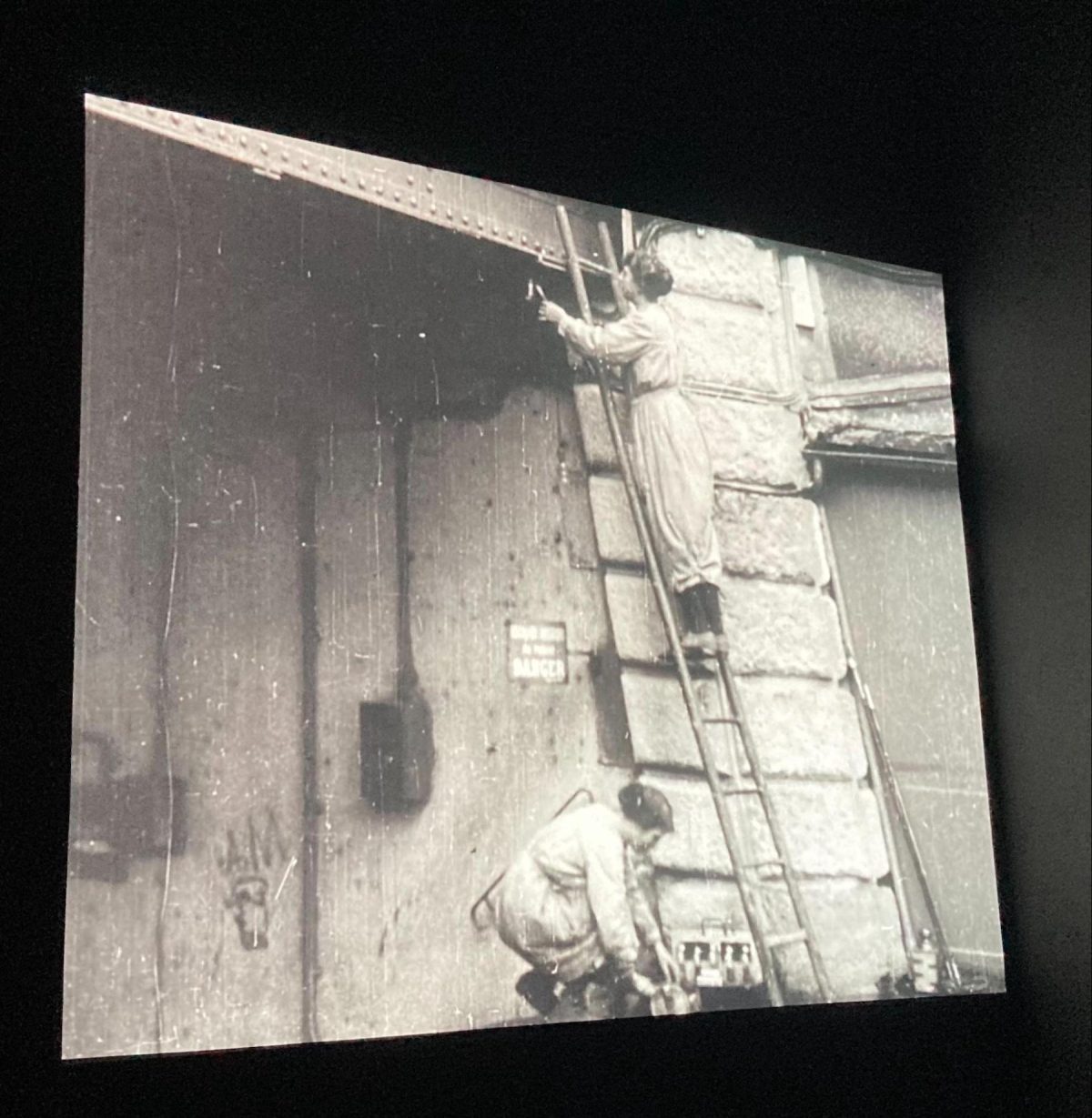

The exhibition’s first images come from World War I-era archival footage. “In France too, women replaced men in traditional occupations,” we read before seeing a short silent film of women operating factory machines, conducting public transportation, and maintaining rooftop heating systems. Throughout the following seven rooms Morineau continues to emphasize economic and social evolution as foundational to, and intertwined with, female artistic exploration.

Film of women working during World War I

A prime example is Josephine Baker, who found artistic and commercial success after moving to Paris in 1925, at the age of 19, to escape segregation in her native United States. She soon became “one of the best paid artists in Europe” by capitalizing on her popularity as a cabaret performer to develop what we would call today her “brand.” One display documents her garçonne look and bohemian lifestyle alongside the menu for a luxury restaurant she opened, the first edition of a magazine she launched, and the packaging of Bakerfix, part of her cosmetics line. But Morineau glosses over (or perhaps leaves it to us to infer) a more complex understanding of the racial dynamics involved in Baker’s unprecedented success. As journalist Rokyaha Diallo has pointed out, Baker’s act “was designed to depict a stereotypical vision of Africa that indirectly celebrated the colonial goal and racist notions of white superiority.”

Elsewhere, Morineau asserts that embracing commercially viable forms of expression (e.g., fashion, dolls, set design) allowed creators such as Marie Vassilieff and Sarah Lipska to earn the financial independence necessary for the development of their artwork. For others, like the Polish-born Stefania Lazarska, supply-chain issues and materials shortages brought about by the Second World War would put an end to their creative entrepreneurship.

I found myself wishing that Morineau would have drawn greater parallels between the financial struggles of women artists in 1920s Paris and those that persist in contemporary France and elsewhere. In 2020 Bruno Racine, a former president of the Centre Pompidou museum (where Morineau also worked as a curator) and a current board member of A.W.A.R.E., authored an official government report on the status of the country’s visual artists and authors. “The median overall personal income of visual artists is €10,000 per year for women,” the report states, while also noting that across all arts sectors, the median revenue gap between men and women is around -25 percent.

Maria Blanchard, “Maternité” (1921)

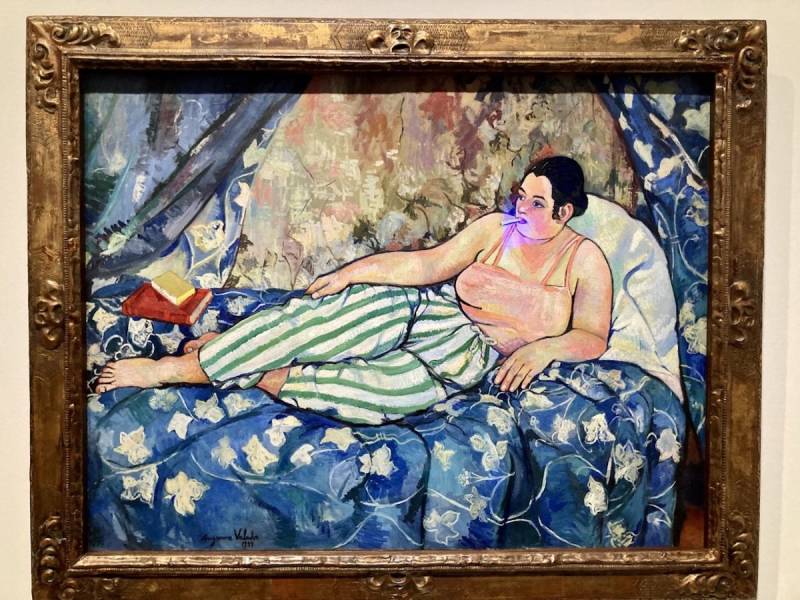

But Morineau is more interested in how contemporary identity politics are embedded in women’s artistic production from a century ago. These concerns materialize throughout a series of rooms in which the female body is disrobed, portrayed through multiple lenses (motherhood, female friendship, aging, sapphic desire), and re-clothed in a way that queers gender identity and presentation. The self-taught Suzanne Valadon’s 1923 oil painting “La Chambre Bleue,” of a woman lounging in striped pajamas, challenges similarly composed, eroticizing images by her male contemporaries. Chana Orloff’s bronze sculpture “Maternité couchée,” from the same year, is an aesthetic exploration of the intimate yet unglamorous act of breastfeeding.

Mornineau devotes an entire room to the historical concept of the “third gender,” an elastic term that encompasses cross-dressing, homosexuality, feminine men, and masculine women. One of the most striking examples is the writer, activist, and photographer Claude Cahun, who wrote in 1930 that, “Neutral is the only gender that always suits me.” A series of her black and white, cross-dressing self-portraits project both bravado and a nuanced grasp of what it means to reveal a self that many people at the time, and today, would prefer remain hidden. These images take on an even greater significance in the context of France’s recent presidential election, and the homophobic and transphobic statements of several candidates.

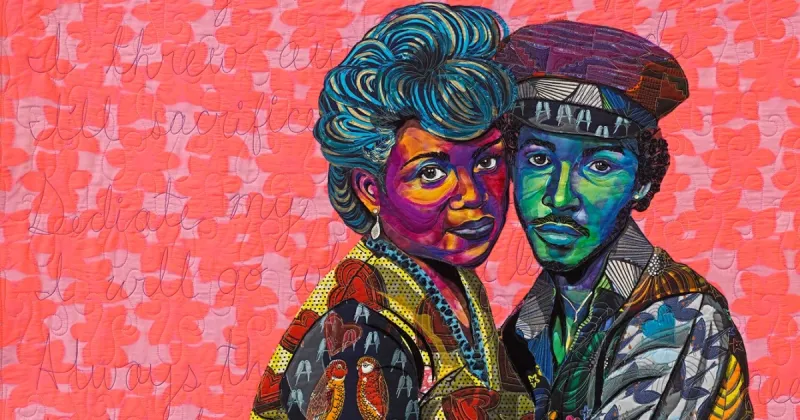

The exhibition finishes with a nod to another timely issue: diversity, specifically the representation of aesthetics, cultures, and bodies that are not endemic to Western Europe. Morineau attempts to show that (wealthy, privileged) women artists were “curious and open to other cultures” because they were “on the periphery of a world in which they wanted to be in the center.” Among these works are Lucie Cousturier’s watercolor portraits, such as “Nègre écrivant,” from her 1921 government-sponsored trip to West Africa, a tradition continued by the ethnographic sculptor Anna Quinquaud (“Portrait d’une jeune négresse,” “Chef foulah,” both 1930) — representations that Morineau qualifies with the unspecific term “non-stereotyping.”

Amrita Sher-Gil’s 1934 “Autoportrait en Tahitienne” (a response to Paul Gaugin’s Tahitian paintings) and one of Tarsila do Amaral’s preparatory ink drawings for her landmark 1928 painting “Abaporu,” inspired by her native Brazil, begin to move beyond Eurocentrism. Despite these noteworthy inclusions, I left the exhibition’s final room feeling that Mornieau had overlooked a more nuanced interpretation of art history: one in which the peoples indigenous to Africa and the Americas depicted are robbed of the power to tell, to show, to interpret their own stories.