In the quiet of her room, Medusa doesn’t hiss. She doesn’t snarl. She doesn’t even blink. She is still — devastatingly so. Behind her eyes, something ancient brews. Not rage. Not vengeance. Memory.

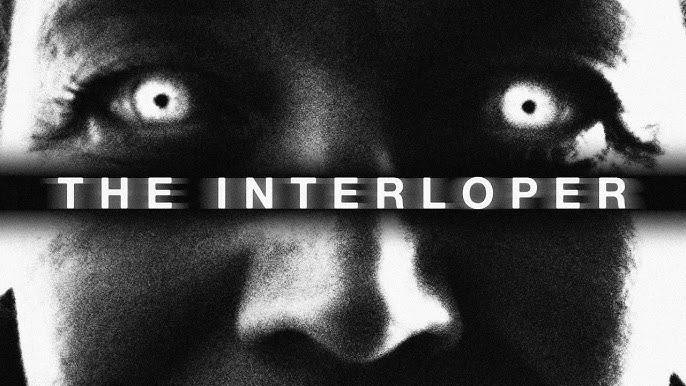

This is how The Myth begins — not with a clash of gods or the turning of men to stone, but with a young woman, alone, clutching the fragments of what she once knew as truth. The film unravels with chilling grace, reframing a figure so often demonized into someone heartbreakingly human.

Medusa has been a symbol for centuries — monstrous, fearsome, cursed. But few pause to ask why. Fewer still ask who she was before the snakes. In this reimagining, the legend isn’t born in punishment, but in betrayal. And that makes it more real than ever.

At Athena’s party — a space presumed safe — Medusa is assaulted by Poseidon. He’s not a god in this version, not in the way myths usually mean it. He’s powerful. Charming. Untouchable. The kind of man who turns his presence into privilege. When Medusa speaks up, when she confides in Athena, she expects arms. Instead, she finds silence. Then the distance. Then blame.

Related article - Uphorial Podcast

MYM: Million Youth Media

The Myth doesn’t give us villains in the traditional sense. That would be too easy. What it gives us is worse — people who could have done better and didn’t. Athena, revered for wisdom, is the most complicated figure here. She, too, has been shaped by the weight of power structures, legacy, and image. Her failure is not in what she does to Medusa, but in what she refuses to do for her.

This is the betrayal the film captures with brutal honesty. It’s not swords or curses that make Medusa dangerous. It’s pain. It’s the death of trust. It's the solitude that follows a truth spoken too soon, to the wrong person, in a world not built for women’s truths.

What makes this film unforgettable isn’t the retelling of the myth — it’s the retaking. It dares to ask, “What if we were wrong about her?” And in doing so, it shines a light on every Medusa the world has ever created. Every woman is silenced. Every survivor who dared to speak and was turned to stone — not by snakes, but by shame.

Medusa's transformation is not punishment here. It's resistance. It’s rage embodied in beauty. Power born from pain. The serpents are no longer symbols of monstrosity; they are her sentinels. Her truth. They hiss not to scare us, but to remind us: she remembers.

The deeper brilliance of The Myth lies in its refusal to sensationalize. The assault is not dramatized for shock. It’s quiet. Terrifyingly ordinary. That’s the point. These moments happen not on warfields or thrones, but at parties. In bedrooms. Between friends. And the consequences echo longer than any divine curse.

Yet amid the darkness, there is power. Medusa does not fade. She becomes. The film doesn’t ask for pity. It demands recognition. It tells us that mythology has always belonged to the storytellers — and that maybe it’s time we let the survivors tell their stories, too.

This is not just a film. It’s a reckoning. A mirror held to myth and culture alike. And in the reflection, we see not a monster, but a girl who was failed, who found power not in forgiveness, but in never being silenced again. And that is the myth we forgot. Until now.