Silence engulfed the audience at Edith Kanaka'ole Stadium in Hilo, Hawai'i, as a group of hula dancers appeared on stage. They moved gracefully in unison, rhythmically depicting a scene of an ancient Hawaiian myth as they bellowed mele (chants). The hula performance, which was part of the annual Merrie Monarch Festival, wasn't a mere spectacle; it was a powerful celebration of Hawaiian culture – and for years, it was banned. The week-long Merrie Monarch Festival (which celebrated its 60th anniversary in April) has been called the "Olympics of hula" and perpetuates the sacred, centuries-old practice of dancing and chanting that preserves and portrays our native Hawaiian language, history, religion, and culture. Every year, thousands of Hawaiians descend on the Big Island to attend the event, while thousands more watch live broadcasts of Hawai'i's 23 best hālau (hula groups) competing on TV.

Yet, the festival is more than just a hula contest; its dance performances, arts and craft exhibitions, and a royal parade through downtown Hilo are considered the biggest display of Hawaiian culture in the world. "It's the one week out of the year where we celebrate being Hawaiian," said Kū Kahakalau, a Hawaiian language and culture expert. "And it's all thanks to the undertakings of King Kalākaua."

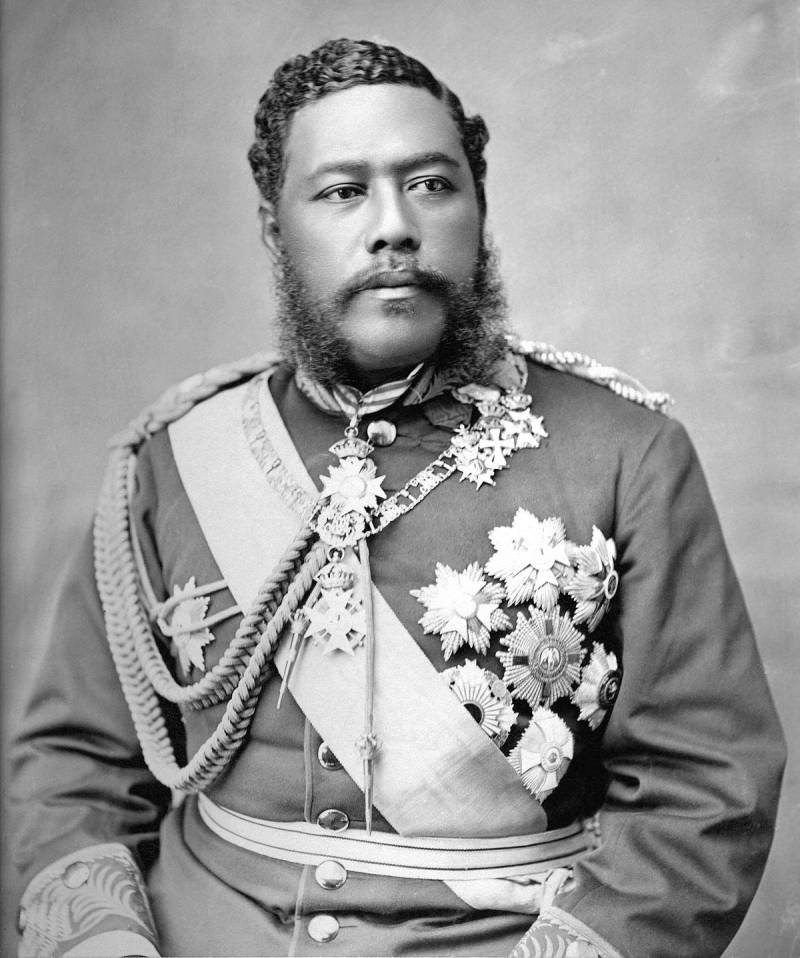

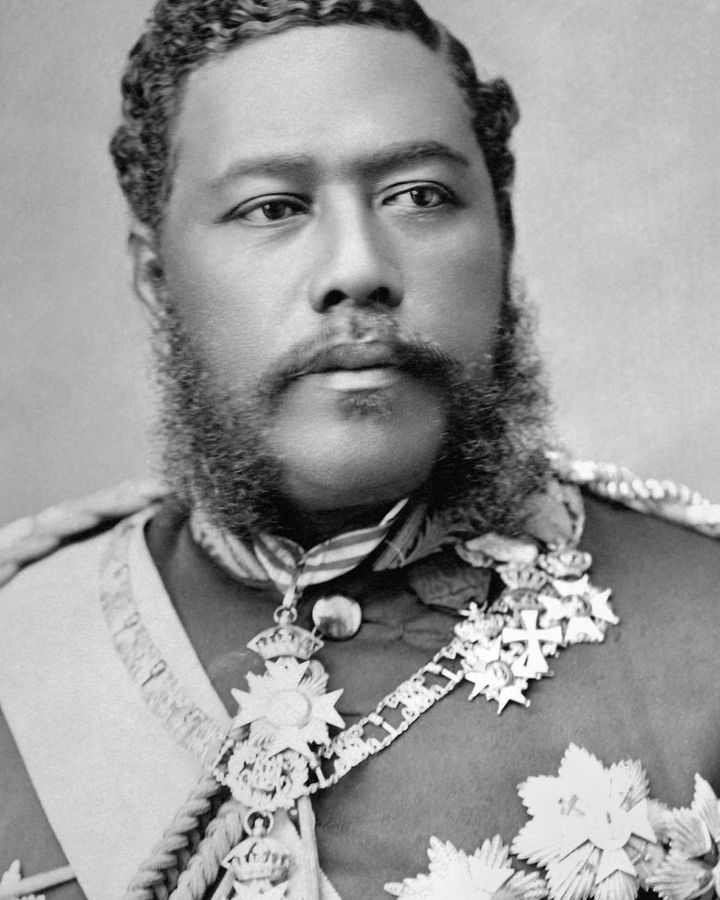

Fondly dubbed "The Merrie Monarch", King David La'amea Kalākaua was the last king of Hawai'i. He ruled the Kingdom of Hawai'i from 1874 until his death in 1891, but his ascension to the throne was nothing short of contentious. Shortly after the death of King Kamehameha IV, whose family had ruled the kingdom since 1795, Hawai'i's legislature decided to elect a native ali'i (noble chief) instead of the king's widow. The decision incited a full-blown riot. As the queen's supporters stormed the Honolulu courthouse, British and American sailors stationed at Honolulu harbor were called in to quell the fighting and Kalākaua took the oath of office the following day. By the time of Kalākaua's reign, Native Hawaiian heritage was at great risk. Christian missionaries had begun arriving on the islands in 1820, introducing diseases that killed Native Hawaiians, converting islanders away from our traditional polytheistic religion, and infiltrating the political system to suppress local culture and beliefs. One of the most significant ways they did this was by banning public performances of the hula, which dance missionaries deemed "vile heathen chants".

Kalākaua sought to restore a unified sense of national pride among Hawaiians, and his reign marked a period of cultural renaissance across the islands. He lived by the motto Ho'oulu Lāhui (Increase the Nation) and sought to remake Hawai'i for Hawaiians – all of which resulted in the revival of traditional customs such as language, music, arts, and traditional medicines that had long been suppressed during the missionary-influenced era of his predecessors. One of his crowning achievements was preserving the hula. As Kalākaua famously proclaimed: "Hula is the language of the heart, and therefore the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people." To many people around the world, "hula" may conjure images of tiki bars, plastic dancers shaking their hips on car dashboards, or something that only happens at beachside resorts. But long before hula was commodified and appropriated, it was a sacred dance among Native Hawaiians – an ancient practice that served as an archive of our stories, beliefs, and way of life. Prior to the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778, there was no written language in Hawai'i. Instead, ancient Hawaiians used oral tradition and hula to pass on their identity and culture from one generation to the next. Even when the practice was prohibited, Hawaiians took hula underground, continuing to teach the forbidden dance in secret in caves and far-flung areas.

As part of Kalākaua's Ho'oulu Lāhui policy, hula experienced a resurgence. In fact, the king's lavish two-week coronation ceremony was essentially a celebration of Native Hawaiian culture, featuring traditional music, hula, and lū'au – all of which had previously been banned. To commemorate his 50th birthday three years later, ho'opa'a (chanters) and 'ōlapa (dancers) performed in public for the first time in years, while a parade wound its way through downtown Honolulu. Today, the Merrie Monarch Festival pays tribute to the proud sense of Hawaiian identity Kalākaua revived. "[Kalākaua] was deeply committed, proud, and knowledgeable about his Hawaiian heritage," said Kahakalau, noting that the king was also the first person to have the Kumulipo (a creation chant that also includes the genealogy of Hawaiian royalty) written down. Yet, Kalākaua wasn't just content to revive Hawaiian customs in Hawai'i; he wanted to share the Kingdom's culture around the world.

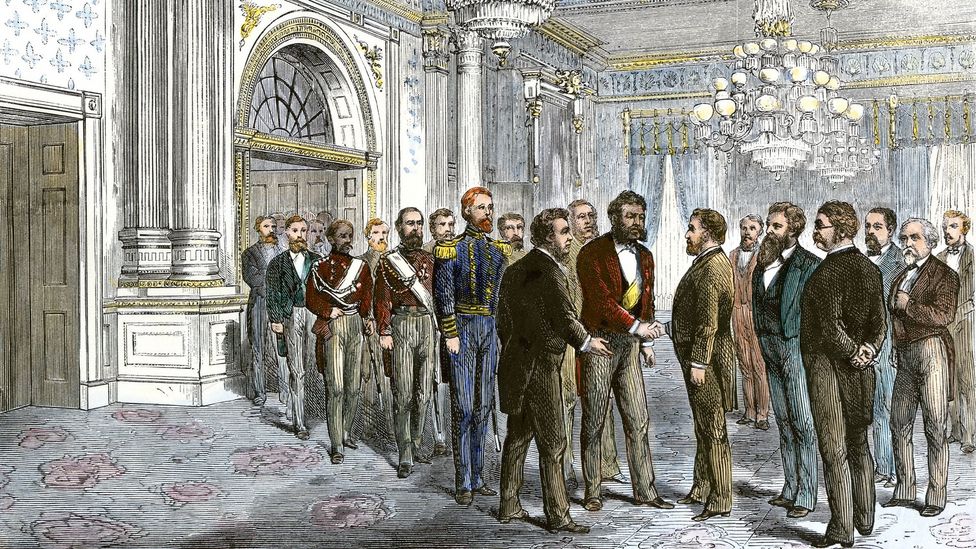

So, in 1881, the "Merrie Monarch" continued the proud Hawaiian tradition of long-distance seafaring by spending 281 days circumnavigating the globe, becoming the first head of state to travel around the world. During Kalākaua's international diplomacy tour, he was greeted by the Emperor of Japan to the sounds of Hawai'i Pono'ī (the Kingdom's national anthem, which Kalākaua had written); he proposed immigration policies with Chinese politicians; he toured the Great Sphinx with the Khedive of Egypt; he was blessed by Pope Leo XIII in Rome; he had tea with Queen Victoria of England, and he boarded a train that was struck by a bull in Spain. In New York, Kalākaua met with Thomas Edison to discuss the possibility of getting electricity to Honolulu. In 1886, the king's wish came true. 'Iolani Palace (which is now a museum and the only royal residence in the United States), became illuminated with electric lights – five years before the White House did.

"He was able to build important relationships, create liaisons, and sign treaties with multiple countries [that benefitted our people]," said Kenneth "Aloha" Victor, a kumu hula (master hula teacher) and designer of Kaulua'e, a made-in-Hawai'i clothing and lifestyle brand. In addition to sending envoys to Europe and Asia, Kalākaua maintained consulates and legations in more than 130 cities across the globe. The Kingdom had 13 consulates in Great Britain alone. Back at home, during an era of increased literacy, Kalākaua met with traditional na kahuna (priests) and na kapuna (elders) to compile many of the ancient Hawaiian myths and chants that are portrayed through hula and mele and write them in Hawaiian. In 1888, he took things one step further and translated these stories into English for the first time in the book, Legends, and Myths of Hawai'i, which he often presented as gifts to foreign dignitaries so they'd get a better understanding of Hawai'i, its culture and its people.

Kalākaua's mission to integrate Hawai'i with the rest of the world also resulted in the creation of the Hawaiian Youths Abroad Program, in which the king selected young Hawaiians whom he felt could become future leaders of the Kingdom and sent them abroad to study things like medicine, law, engineering, foreign languages, and art. More than 100 years later, the program's legacy still echoes across the islands: Princess Abigail Kawānanakoa, the granddaughter of one of the students the king sent abroad, played an instrumental role in restoring 'Iolani Palace and was a staunch supporter of native Hawaiian rights until her death in 2022. A multi-hyphenate in every sense of the word, Kalākaua embraced modernity just as much as he valued Hawaiian culture. He was a voracious inventor, designing blueprints for tornado-proof ships, fish-shaped torpedoes, sealed bottle caps, and rangefinder scopes. He even had a telephone installed that connected 'Iolani Palace where he lived and worked to his private boathouse less than a mile away, where he'd often be found hosting royal lū'aus for foreign dignitaries and heads of state.

For Hawaiians today, Kalākaua is much more than just a Renaissance man. "When Kalākaua traveled [abroad], he promoted and shared our culture with the world," said Ana Kon, a Hawaiian cultural specialist based in Hilo. "It's why, more than a century later, we continue to honor his legacy today at the Merrie Monarch Festival." For those unable to snag tickets to the Merrie Monarch Festival's highly coveted hula competitions, there are still plenty of opportunities to participate in the festivities. Hilo's Afook-Chinen Civic Auditorium and Butler Buildings host a vibrant arts and crafts fair featuring the creations of more than 150 local artisans and brands from across Hawai'i. "Our 'aloha wear' is a celebration of hula," said Victor, of his clothing, which he said honors the people, places, and movements in Hawaiian culture. Of course, Kalākaua's legacy lives on beyond the festival.

In many ways, every hula step, lū'au gathering, and Hawaiian-language phrase is a nod back to our last king's efforts to revive our customs at home and introduce them around the world. Visitors can experience this first hand at O'ahu's Polynesian Cultural Center, which hosts a traditional Hawaiian lū'au paying homage to Queen Lili'uokalani (Kalākaua's sister, who succeeded him until US sugar planters overthrew the Kingdom in 1893), while the Queen Emma Summer Palace in Honolulu offers contemporary hula lessons for adults.

On Maui, immersive experiences at the Grand Wailea include an E Ala E oli (chant) in the mornings on the beach, while interactive language lessons teach guests how to pronounce words in ʻŌlelo Hawai'i (Hawaiian). Beachside resorts like Outrigger Reef in Waikiki Beach are adopting a regenerative tourism approach at its A'o Cultural Center by allowing guests to meet traditional Hawaiian navigators and canoe builders, teaching them how to use traditional Hawaiian tools and – yes – participate in hula lessons. "It all spawns back to [King Kalākaua's] creed," said Victor. "That hula is the heartbeat of our Hawaiian people."