The Laurence Fishburne-produced and Laura Checkoway-directed documentary, The Cave of Adullam, which premieres tonight at the Tribeca film festival, and repped by CAA Media Finance, ICM Partners and Paradigm–is a love letter to masculine vulnerability. Cave leader Jason Wilson uses a quote from Frederick Douglas for reference, “It’s easier to raise boys than repair broken men.” Through martial arts, meditation, discipline, and emotional expression, he’s helping the young men of Detroit create a new way of living beyond the temptations of crime and gang culture.

His teachings encourage young men to cry, be upset, and be okay with expressing their feelings, which forgoes the idea that Black men must bottle up their feelings because it’s not what men do. The film follows four young men as Wilson reprograms their understanding of masculinity and gives them problem-solving tools to break the generational trauma of manhood.

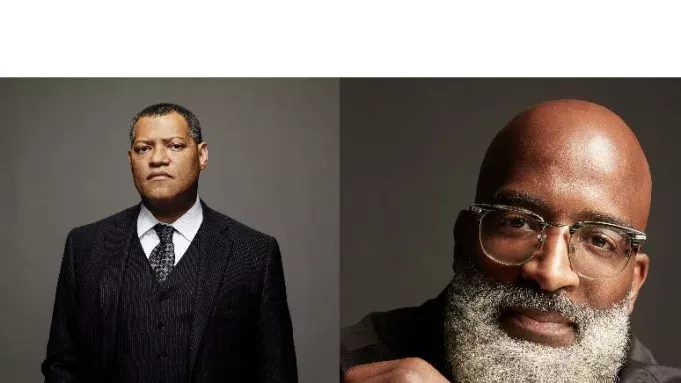

Deadline spoke with Fishburne and Wilson about their joint endeavor and why helping young Black boys is crucial, and how the training helps cultivate a brighter future for themselves in a society that forces Black children to grow up too fast.

DEADLINE: How did you [Fishburne] Jason and director Laura Checkoway come together for Cave of Adullam?

FISHBURNE: It’s interesting because I think my relationship with Jason started well before I met him. He has a relationship with my work and found some of the work that I have done useful for what he’s doing.

WILSON: I’ve been a fan of Laurence forever, you know, especially Boyz n the Hood, and I saw him as a father figure. However, when he played Morpheus in The Matrix, I saw the ultimate father figure. Part of the Cave’s curriculum is based on the philosophies in the film. Like Neo (played by Keanu Reeves), I had to revisit my trauma of growing up with a verbally abrasive father.

We had a video that went viral on YouTube called breaking through emotional barriers in 2016. When it went viral, I was contacted by three film producers, one of which was Roy Bank. He stayed in touch over the years, and I decided to move forward with him. Fast forward, and Laurence sees the sizzle reel.

FISHBURNE: Roy brought Jason to our attention, told us about him, his program, his ideas, and what he was doing, and showed us a little bit of a sizzle reel. This is right in line with our mission and the kind of lives that we want to illuminate.

DEADLINE: Why was it important to you to create a space like The Cave of Adullam?

WILSON: The Cave was born of my desire for a man or a father figure to train me in the ways of being a man. Looking for someone who wouldn’t condemn me if I felt weak, or someone who would encourage me and affirm me. Even today, a lot of young boys are deceived by misleading mantras, like “no pain, no gain,” and “big boys don’t cry.” It was imperative for me to create a space where boys could feel safe, where they can really express what’s going on, their toxic thoughts, and emotional wounds before they do something detrimental. I incorporated martial arts because it gave me an alternative to an opportunity to really express what was going on without, you know, jeopardizing my future. It helped me release the anger that I felt from my father, not really being active in my life.

DEADLINE: You’re creating a new way for young men to process that isn’t someone yelling in their face or someone screaming at them to get it together.

WILSON: There were a lot of boot camp programs that began to fail at an alarming rate. I participated in about three of them before realizing you can’t scare a boy straight. Black boys in Detroit didn’t need that. They need healing. I went from just martial arts and mentoring to start incorporating therapy and opportunities for them to meditate and discuss what’s going on internally.