“I often think that many of the works that are canonically labeled ‘great’ are simply those that lingered longest in individual memory. And that they lingered because while looking at them someone was moved, touched, taken to another place, momentarily born again.”

The late bell hooks, who died Wednesday at the age of 69, was a prolific and profoundly influential critic. In dozens of books, beginning with the seminal 1981 volume Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, she lay the groundwork for an intersectional feminism, one resisting the hierarchies of race, class, and sex. Committed to serving an audience of ordinary people, she wrote about cinema, television, and self-love with equal depth and intellectual rigor—not in the alienating jargon of academia, but in an accessible language that felt conversational, intimate, and generous.

“My joy is when people are working with my work,” she said in conversation with Theaster Gates and Laurie Anderson in 2015. “It’s not in celebrity. It’s not in fame. It’s not in money—[it’s] when people say, ‘This book changed my life.’”

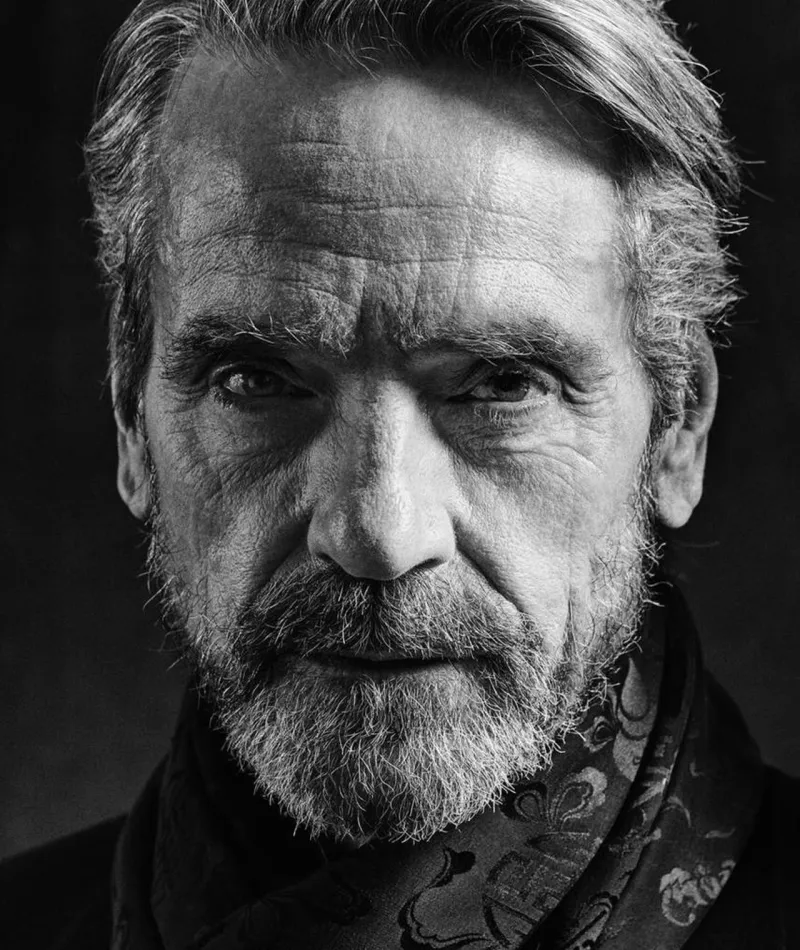

bell hooks signs her book for Robert Wood, 6, during the celebration of Karibu Books’ 10th anniversary at Prince George’s Plaza in Hyattsville, MD. Photo: The Washington Post.

Predating hooks’s discovery of feminism, there was art. As she recounted in her 1995 collection of essays, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, from a young age she recognized art as a site of possibility, “a realm where every imposed boundary could be transgressed.” In high school, growing up in a segregated Kentucky town in the late 1960s, hooks (then known as Gloria Watkins) recreated a Willem de Kooning painting for an art-class assignment: “I loved the work of painters using Abstract Expressionism because it represented a break with rigid notions of abstract painting; it allowed one to be passionate… it was a critical intervention, an expansion of a closed turf.”

As a critic, hooks looked to art for its spiritual and emotional resonance, writing often about a work’s transformative powers and the necessity of beauty in one’s life. In the works of Margo Humphrey, she found renewal; in Andres Serrano’s, healing and restoration. In the art world itself, however, she found what she termed an imperialist-capitalist-white-supremacist-patriarchy. Narrow Eurocentric traditions offered no serious critical interrogation of Black artists. Black women were roundly ignored, and even the most famous of Black men were smugly dismissed.

“It is amazing that so few critics discuss configurations of pain in Basquiat’s work, emphasizing instead its playfulness, its celebratory qualities,” hooks wrote in a searing 1992 Art in America review, “Altars of Sacrifice: Re-membering Basquiat.” Below the carnivalesque veneer, she read symbols of pain and mutilation at the hands of white imperialism, whereas white critics had only offered surface-level readings of Basquiat based on the precedents of white artists. Unimpressed, she wrote of the white supremacist implications of designating figures like Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol as standard units of measure for artistic greatness. “To see and understand these paintings,” she wrote, “one must be willing to accept the tragic dimensions of black life.”

To hooks, the act of art-making was a way of decolonizing the mind and the imagination; a preservation of self; and an act of resistance. Likewise, with her criticism and the subsequent compilation of Art on My Mind, her hope was that she could “ultimately create a revolution in vision” that would properly recognize the work of Black artists. She leaves behind a tremendous legacy, an endless list of quotable passages, and a cultural landscape richer than when she found it. bell hooks is sorely missed.

SOURCE : artnet