NEW YORK — In 2014, the Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted a large and revelatory survey of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, one of the leading sculptors of 19th-century Europe. It left the impression of an artist of extraordinary talent and inventiveness, maybe not as great as his compatriot, Rodin, but close enough.

Carpeaux was the Brahms to Rodin’s Wagner. He was inventive but with a classical bent, and a tendency to sweetness that sometimes crossed into the saccharine. He also served power unapologetically, making flattering, even kitschy images of the royal court and family of Napoleon III during the Second Empire.

Since that survey, the Met has acquired another key work of Carpeaux’s, one of two marble busts depicting an enslaved woman, known by the words inscribed on its base, “Why Born Enslaved!” Now the museum has mounted a smaller but much more focused show devoted to that work, including versions in terracotta, clay and plaster, as well as other sculptures, medallions and decorative pieces that reference the abolition movement in France and its colonies. It is accompanied by a book of probing essays about the role of ethnography and colonialism in shaping how people of African descent were represented in France during the 19th century.

“Why Born Enslaved!” is a troubling and compelling image of a woman, with rope cutting into her exposed arms and breasts, and a defiant but anguished look on her furrowed face. The original of what became a widely reproduced luxury object — the Empress Eugenie owned and prominently displayed a copy — was made in 1868, just three years after the end of slavery in the United States, but 20 years after the abolition of slavery in France’s Atlantic colonies. Unlike an equally famous image of abolition, Josiah Wedgwood’s c. 1787 medallion of a Black man kneeling, in chains, pleading the words “Am I not a man and a brother?,” Carpeaux’s bust is a postlude to slavery in France, more of a congratulatory patriotic exercise than a direct appeal to the conscience. And that makes it particularly problematic.

If slavery was already abolished, what feelings are this bust meant to inspire? The catalogue essays point to the obvious sensuality of the woman, to the erotic drama of her captivity and the way that invites viewers, especially men, to objectify her for visual gratification. They also raise doubts about the depth and sincerity of Carpeaux’s anti-slavery views, and by extension, the sincerity of France’s belief in the genuine equality of the people in its far-flung empire.

“Why Born Enslaved!” is presented as an exercise in 19th-century ethnography, an effort to codify and generalize racial types, which became intertwined with a larger project of assimilating colonial subjects into a universal idea of French citizenship and identity.

At the Whitney biennial, more serious art for a more serious time

Ethnographic sculpture was perversely complicated with a wild mix of objectives and motivations, and this exhibition does a good job of revealing that complexity. On one hand, it involved a new and more rigorous look at its subjects, an effort to depict people of different races not by the conventions of academic art, but through actual attention to the world and its variety. And one can’t look at “Why Born Enslaved!” (and other sculptures in the show, including the sumptuous works of Carpeaux contemporary Charles Henri Joseph Cordier) without sensing the presence of real people as source and inspiration at some point in the creative process. In the case of the Carpeaux bust, it may have been Louise Kuling, a Black woman from Norfolk, who was living in Paris at the time.

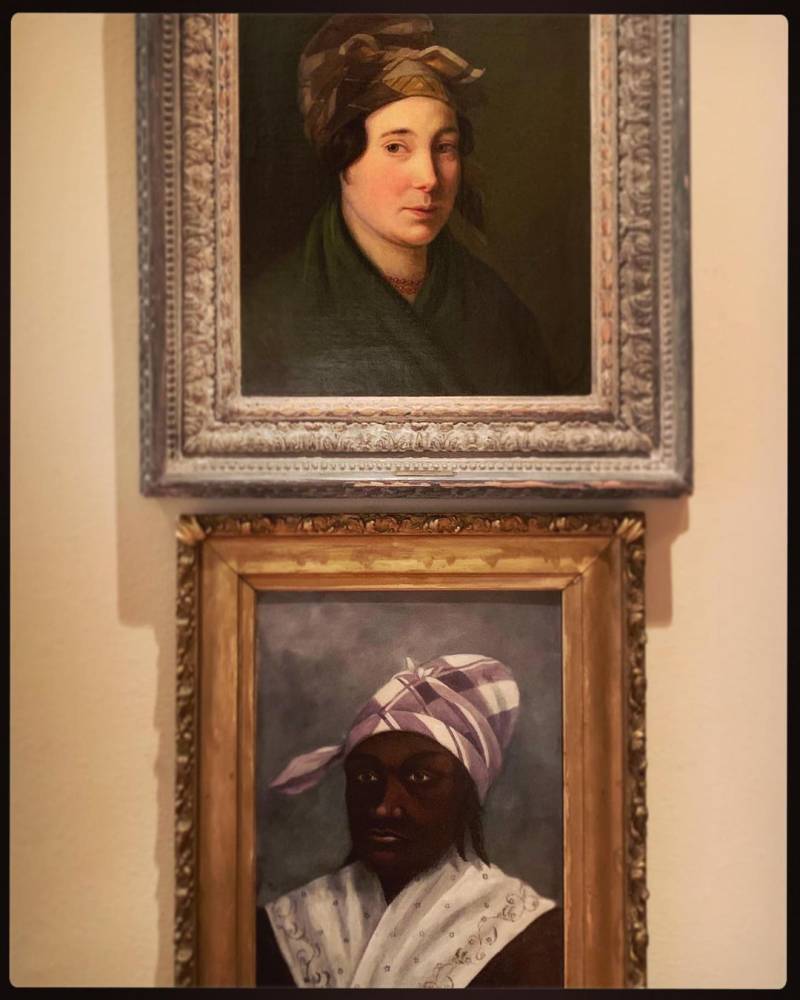

Charles Henri Joseph Cordier's “Woman from the French Colonies,” 1861. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

But the new and more rigorous effort to look at the world also was part of the pseudoscientific goal of making broad generalizations about the races and their essential nature, with a hierarchy in which the White male artist from Paris was natural arbiter of all distinctions. Cordier, who draped his African figures in flowing robes of marble or bronze, may have been in search of the beauty unique to other races. But the particular beauty he found, and the way he dressed up his figures with classical references, suggest he was mythologizing his subjects within a decidedly European sense of what was attractive and universal.

The Met exhibition, which includes about 35 objects, features two contemporary works that demonstrate the long shadow Carpeaux’s bust has cast. Kehinde Wiley’s “After La Négresse, 1872” is made of cast marble dust and resin, showing a young Black man wearing a Lakers jersey, with his head turned in the same, awkward way as the Carpeaux figure it references. It was part of a series of 250, and the overt commercialism of its reproduction references the commercial forces that drove Carpeaux to make multiples of his work. It also appropriates, glibly, the eroticism of the original, recasting it in homoerotic terms.

Far more substantial and moving is Kara Walker’s 2017 “Negress,” a plaster cast made from Carpeaux’s bust, but displayed on the floor, illuminated by a single light. The plaster appears as a void bounded by the famous, anguished face, and suggests both the desire and futility of any effort to get “inside” the head of the unknown figure who modeled for Carpeaux.

Kara Walker's 2017 plaster work “Negress,” 2017. (Kara Walker/Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York/Photo: Jason Wyche)

That gesture summarizes the darkest question raised by the show: What happens as we look intently at this face in front of us? Does our looking simply extend the exploitation that Carpeaux both dramatizes and indulges? Does it recolonize this woman and, by extension, all women of color? Is there any innocent participation in this exhibition?

The National Gallery surveys the multiple histories of the African Diaspora

Some of the essays in the catalogue clearly suggest that there can be no pleasure in this object that isn’t fundamentally an extension of the violence that it supposedly condemns. That makes this Carpeaux exhibition a far darker enterprise than the 2014 show, which acknowledged the complexity of the artist and his intimate engagement with the corrupt and imperial forces that led France at the time. But the stakes of the 2014 show weren’t as high, and guilty pleasure could be snatched from its darker imputations.

There is no such offering here. That leaves this bust, in its many iterations, in a curious place. It embodies a history that must be told and it implicates us in that history. It does so because it is a highly successful artistic object, clearly expressive, dramatic and engaging. We leave with the paradoxical sense that we are both condemned and privileged to live with it, as it casts an ever longer shadow over the history of race and representation.