A new show at the Museum of London tells the history of a scene that shaped British music, streetwear and slang – and launched the careers of Ghetts, Skepta and JME

Born in early 2000s east London, grime, an unapologetically dark music genre, was created as an outlet for a generation of young people living through a time of unprecedented violence and profound social change. This was post-punk angst on wax – a heady mix of dancehall, jungle and UK garage, inspired by Jamaican ragga toasting and the storytelling of US hip-hop.

More than two decades later, the story goes on. “Grime is one of those genres that once it’s in you, it never leaves,” say Roony “Risky” Keefe. He is talking from the black cab that he operates during the week; he’s just got back from registering the name of his newborn child. “The first letters of his first, middle and last name spell out BBK,” says Keefe, referring to the grime collective Boy Better Know, whose members include JME, Skepta, Jammer and more, “and that was by coincidence!”

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

Known simply as Risky to the grime community, Keefe was one of the first to document the genre, in a series of DVDs called Risky Roadz. Before YouTube, DVDs made stars out of the MCs, DJs and producers creating grime’s futuristic sound. And while the world has long since moved on from the format, the music’s influence is everywhere: from the raw energy of UK drill, to the streetwear and slang of Britain’s inner cities, via Top Boy, the acclaimed crime drama that stars many of the scene’s biggest names.

Keefe says of his collaboration with the Museum of London: “They wanted me to do a series of interviews in my taxi at first, picking up some of the artists and going around the city; the whole exhibition kind of came from that.” For the show, titled Grime Stories: from the Corner to the Mainstream, Keefe called on Jammer, who as an MC and producer has been integral to grime’s advancement for more than 20 years. His “dungeon” – a basement situated in his parents’ house in east London, which has been a creative hub and safe space for grime since day one, features heavily in the exhibition.

“Risky hit me up and said: ‘We can’t really do something like this without giving you a shout,’” says Jammer. “He explained that it was about showing people how the foundations of grime were laid and how this movement enabled all of us in it to rise up.”

For Jammer and his peers, grime was “the only thing we knew how to do to make a better life for ourselves”, he says. “Grime is like our therapy: you go into it with your pain, get your lyrics out – 50 guys in one room, screaming down the mic, getting out whatever their frustrations are – and then you get better and you learn. It’s a real confidence-builder.”

The free exhibition, which opens on 17 June, will display images from Keefe and others’ archives, video inserts, memorabilia (including Keefe’s first camera, bought for him by his celebrated Grime Gran), and other trinkets that will leave visitors with a deeper understanding of a movement that has lifted so many lives and created so many careers. “This is a monumental moment in the UK,” says Jammer. “Especially for Black British culture.”

Microphone champions: five images from the exhibition

Photograph: Roony 'Risky' Keefe

The Movement studio session

Producer Lewi White’s work with the Movement, the now defunct crew featuring Ghetts and Devlin, helped push the limits of where grime could go sonically. This session at White’s studio on Cable Street, east London, led to some of the tracks on their mixtape Tempo Specialists.

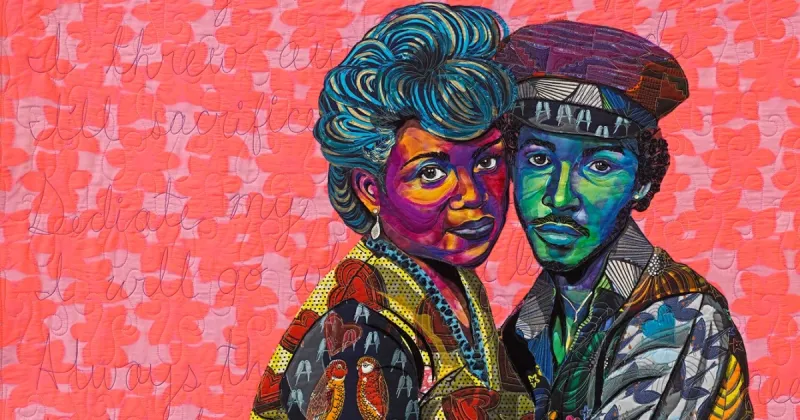

Red Hot Entertainment (pictured top)

“This is Red Hot Entertainment, on an estate in east London,” says Keefe. Mostly known for their viral song Junior Spesh, Red Hot had a short-lived but vital career in grime. East London tower blocks and rooftops hold a special place in grime’s heart; it’s where Black, white and Asian kids – from their respective estates – linked up to spit their rhymes before going to local youth clubs to perform them.

Photograph: Roony 'Risky' Keefe

Skepta at Club 333

“Taken in 2006, this shot shows Skepta performing at Chantelle Fiddy’s Straight Outta Bethnal at Club 333 in Shoreditch, east London,” says Keefe. “It was one of the first times I saw him live. He smashed it and has consistently achieved greatness ever since – from winning a Mercury to going platinum around the world.”

Photograph: John Chase/Museum of London

Jammer’s grime dungeon

“I remember Tinchy Stryder saying that when you got the invite to the basement, that’s when you knew you were someone,” says BBK MC and producer Jammer. “It’s like a sacred place. A lot of artists made their early music there: D Double E, Skepta, JME, Kano … the list goes on.”

Photograph: Roony 'Risky' Keefe

JME live at Eskimo Dance

Shot in 2019, this image of Boy Better Know CEO JME was taken at Eskimo Dance – one of grime’s biggest club nights, which began life in 2002. The show, a sold-out affair at the south London venue Printworks, drew 6,000 people from all over the country – with moshpits aplenty – in a year when many critics were claiming the scene was “dead”.

Grime Stories: From the Corner to the Mainstream opens 17 June at the Museum of London.