Following independence, a sense of excitement and cultural renaissance swept across many African countries.

It was a time of creativity and liberation, writes Precious Adesina.

When Sanlé Sory was photographed for his ID card in 1957, he was surprised to find out how expensive it was, which gave him the idea to start his own business.

"I paid about 25,000 [West African] francs [£32] and a bottle of whisky to a Ghanaian photographer, Kojo Adamako, to become his apprentice for about two years," the Burkinabe photographer Sory tells BBC Culture. "That was the beginning of a new career, right when my country was about to become independent.

Read Also: This is my Story - Episode 2 | Uphorial Media with Data

" By the mid-1960s, Sory had opened Volts Photo, a photography studio in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second largest city in Burkina Faso, which quickly took off.

At the start of Sory's career, in 1960, 17 African nations had become independent. In the years that followed, photographic studios sprung up around the continent, by default documenting how each country embraced their newly found liberation.

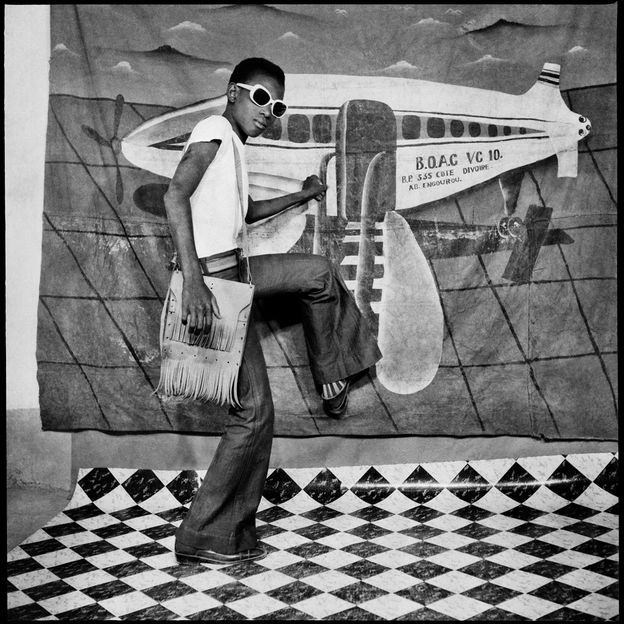

"There was a total sense of freedom back then, and most people looked down on the colonial past [of their country]. They wanted to be themselves," says Sory. His work – and studio images by other photographers across the continent at the time – can be found in Africa Fashion, an exhibition at London's Victoria and Albert Museum.

The show explores fashion across Africa from the mid-20th Century to today, looking at photography, textiles, music and the visual arts. But it isn't just about style. "Our aim, through the exhibition, is to use fashion as a catalyst to give our audiences a glimpse of the myriad of cultures and histories on the continent," lead curator Dr Christine Checinska tells BBC Culture.

The period of decolonisation ignited a new sense of excitement in artists of many countries across Africa

The exhibition begins with the independence era in Africa, and takes viewers on a journey from there up to today and the fashion currently emerging from the continent. Contemporary pieces include works by the Nigerian label Orange Culture – that challenge the ideas of "masculine clothes" – as well as bespoke outfits.

"We start in the independence era because, for many, it epitomises pride in being black and African," says Checinska. The period of decolonisation ignited a new sense of excitement in artists of many countries across Africa. It was a time of African cultural renaissance, with many using their medium to explore their relationship with their country. "Naturally, people were embracing the opportunity to form their own identity. They felt the freedom to express themselves without being under colonial eye," says David Hill, owner of West London photography space David Hill Gallery.

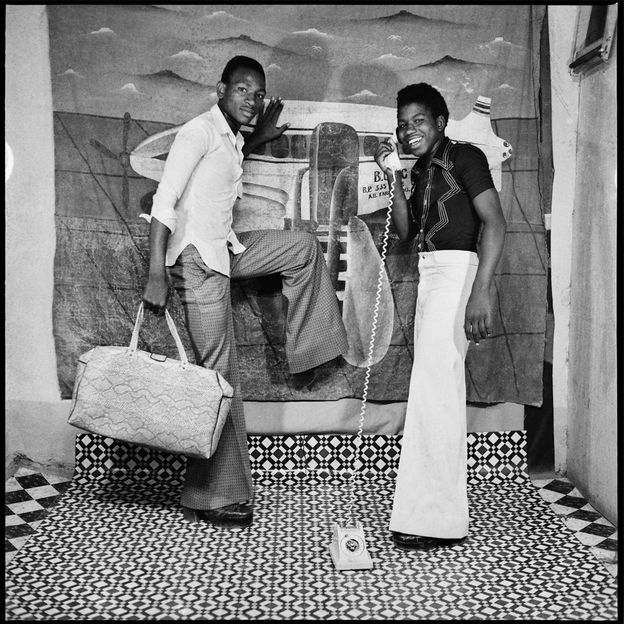

There is a sense of joy and optimism in the work of Sory – as with Je Vais Décoller (1977), shown here (Credit: Tezeta/ Courtesy of David Hill Gallery)

Studio photography was not new, but faster shutter speeds and cheaper development processes, alongside the plethora of new studios, allowed people to record and celebrate even minor achievements in their lives. "There was a need for people to have photographs of themselves to give to friends and family," Hill tells BBC Culture.

Capturing a moment

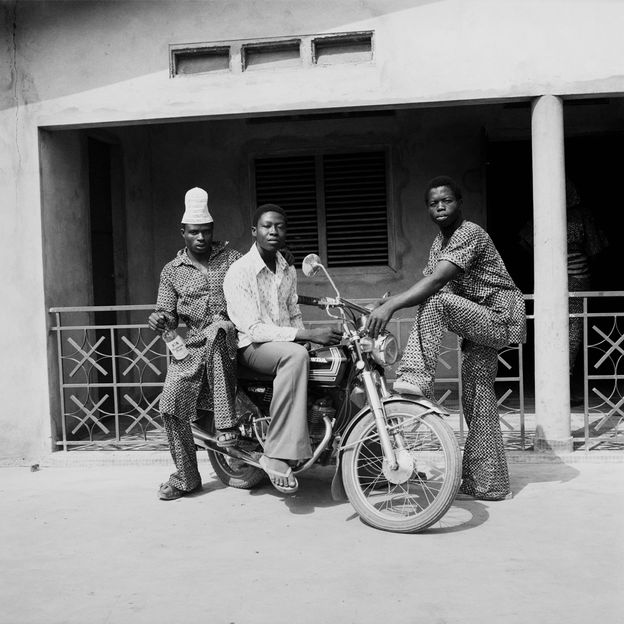

The Beninese photographer Rachidi Bissirou, whose work is also in the exhibition at the V&A, regularly snapped people with their motorbikes. In an untitled picture from 1978, a young man called Albert sits on a Honda alongside two smartly dressed friends. "They're often guys in their late teens, early 20s, with their new shiny bike, wanting to record the moment. They might ask for six photographs, which are generally postcard sized," says Hill.

People felt free and proud, and this was expressed in their clothing and attitude – Rachidi Bissirou

In Sory's photographs, clients frequently posed in front of vibrantly painted backdrops, depicting, for instance, a beach, an airplane, often holding various props to complement the scene. In Allo, on Arrive!, taken in 1978 by Sory, two men in flared trousers pose in front of a backdrop of a plane. One stands as if boarding the aircraft, while the other stages a phone call on a rotary telephone. "It was quite a common thing for people to have a box of props," says Hill, "Plastic guns, swords and shields, portable radios. That kind of thing."

Albert on his Honda with Two Friends (1978) by Beninese photographer Rachidi Bissiriou (Credit: David Hill Gallery/ Rachidi Bissiriou)

However we perceive these pictures today, many photographers of the time saw their practice as a trade rather than an art form, which meant they were often oblivious to what was happening in the medium outside their immediate community. "I wasn't aware of any other photographers back then. I just saw photography as a way to earn some money and start a career," says Sory, adding that people posed in whatever they wanted. Much of Sory's work looks to us now like fashion photography, though it was never intended as such. "People felt free and proud, and this was expressed in their clothing and attitude," adds Bissirou. "I sometimes helped them to pose, but the clothes are their own."

Beyond studio photography, independence impacted many aspects of the cultural sphere across Africa. In 1966, Senegalese President Leopold Senghor held the First World Festival of Negro Arts (FESMAN) in Dakar, the first modern event celebrating global black culture. It was an opportunity to commemorate the arts in newly independent African nations, and included more than 2,000 writers, artists and musicians from across Africa and the African diaspora. "The sophistication of the continent was shown through creativity in the arts," says Checinska, adding that the "power of creativity to affect change" was apparent throughout the festival.

Some artists also used independence to question the practices of their country. The cover artwork by Lemi Gharioukwu for Nigerian musician Fela Kuti's 1989 album Beast of No Nation is displayed at the start of the exhibition. "Beasts of No Nation condemned the post-independence generation of lost politicians, lamenting the missed opportunities and broken lives," writes historian Gus Casely-Hayford in the exhibition catalogue.

Kuti is widely considered one of the most influential musicians to emerge from post-independence Nigeria, and his music still impacts artists and political conversation today. "The album tapped into the wider cultural backdrop of the continent's crippling frustrations and bitter disappointment with its politicians and business communities, but it also reflected the indefatigable energy of Africa's creative sectors and their irrepressible drive to create beautiful things in the face of unimaginable challenges."

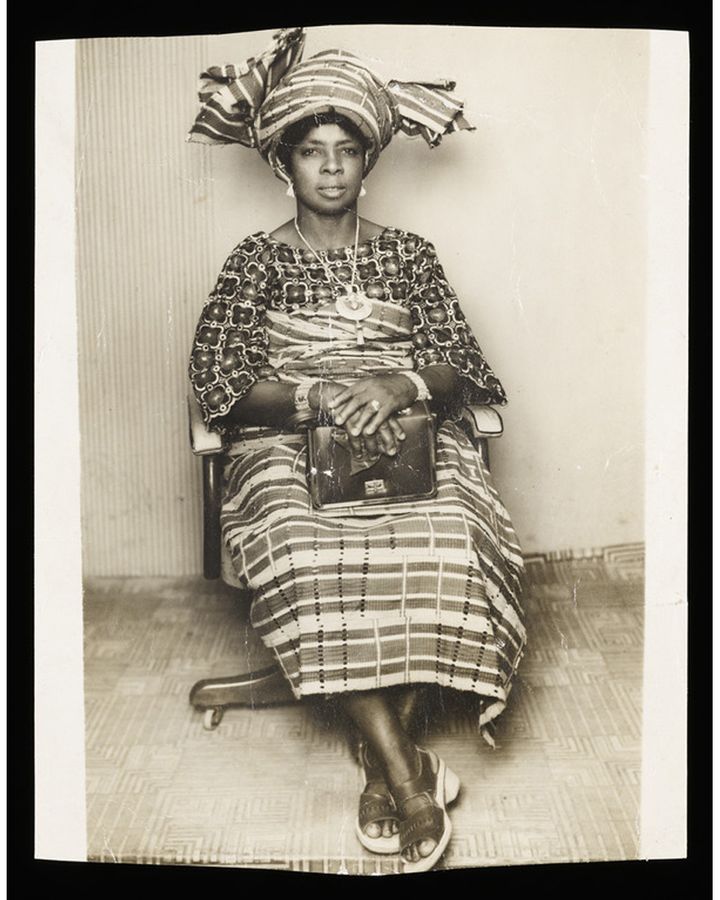

Esther Suwaola, photographed in Akure, Ondo, Nigeria in 1960, the year that saw many African countries gain independence (Credit: Victoria & Albert Museum)

That said, even with similarities between countries, Africa Fashion is careful not to homogenise the entire continent, making room to show the differences between countries. "We want to keep it open-ended," says the curator. "If you look at gallery text or whenever we speak about it, we never use the singular. It's always African fashions, plural, because we want to recognize that they're multiple things."

And by showing the continent from the lens of the people living there, a more authentic sense of African countries can be seen, free from overt stereotypes and Western prejudice. "If you've got a Western photographer going in, it's bound up with 400 years of problems, if not more," says Hill. "It's a more honest picture of the society, the way people were living, what they wore and how they lived their daily lives."