Hard to believe, but Femi Kuti has been on the international scene for some 24 years. He was always known as the son of Fela Kuti, but he may soon be better known as the father of Made [MAH-deh] Kuti, his 26-year old son. Father and son released a double CD in 2021 called Legacy, one volume for each artist. The difference is that Femi’s album Stop the Hate, continues his tradition of high-energy, jazz-fueled Afrobeat with his juggernaut band Positive Force. Whereas Made’s album, For(e)ward, is entirely recorded by the artist, literally playing all the instruments: horns, guitars, keyboards, bass, drums and percussion. The result is a new direction for the genre, more experimental, bringing in influences from rock and techno.

This month, Femi begins his first U.S. tour since the pandemic, and he’s bringing Made along, including a show at New York's Webster Hall on Friday, June 10. See Femi and Made tour dates here. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached the two artists in Lagos by Zoom. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Femi, we’re looking forward to seeing you in New York next week. It's been a long time since we last met in Lagos in 2017. And Made, very nice to meet you. We've been enjoying your album. Just to start out, how do you guys manage during the pandemic?

Femi Kuti: The Shrine had to be closed for over a year. It's been like everywhere else. We tried to go on a tour last November, and the tour had to break down because of the Omicron virus started. We lost about $30,000, so it has been kind of disastrous. But of course it's for everybody, not just us. The world is trying to heal.

Made Kuti: During the lockdown in 2019, I think I used most of that time to rehearse for the recording of the album. So that was one good thing that came out of it.

I have heard that from a number of artists. It was a good time for staying at home and being creative. Let's talk about this album. I find the contrast between your two approaches quite interesting. I'll start with you, Femi. I'm always impressed with the velocity and force of your songs. They hit so hard. There's an incredible sense of urgency about them.

Femi Kuti: I think it's more to do with my character, the hustle in Lagos, the hustle to survive, to excel. I had a kind of street education. It was tough. All I had was my music and my energy. And when I started, it was like getting on a moving train. I didn't know where it was going to take me. I knew I can’t step down. I can't stop. Sometimes I was just dead tired, but I had to get up the next day. If you’ve seen the tours, it's a very hectic tour. I'm clocking 60 very soon, but it seems that I’m going to do this forever.

Well, you don't sound tired. But I understand about touring. It is brutal.

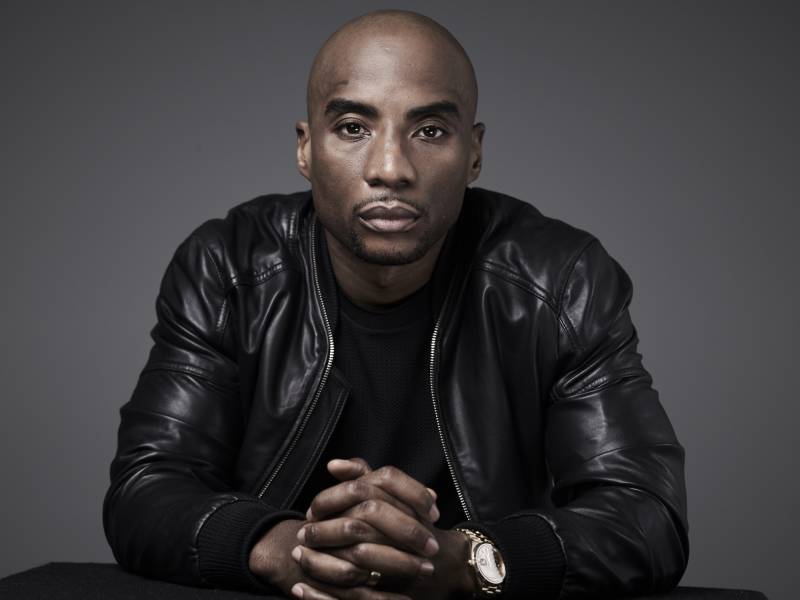

Femi Kuti (Photo by Sean Thoms)

The urgency comes from the panic in my mind. We have to start doing things right. Because Africa is suffering too much. Now there's so much suffering globally. There's climate change. I think it's the urgency of how my mind is, a kind of panic where we need to do things quickly. We need to start doing things right. It's all part of the emotions that come from my mind, my soul, from my being, to express this urgency in the music as well. The force and the dynamics, the energy, the horns and all that, the rhythms—it's like a very strong tidal wave or a tornado telling me to quickly act. Like I said, it's my character.

I feel it. The messages in the songs are crystal clear: “Land Grab,” “You Can’t Fight Corruption with Corruption,” “Na Bigmanism Spoil Government.” It's all right out there. It makes me wonder. You are a major public figure in Nigeria now. What is your relationship with people in the government? Do you see any bright spots there? Are there any people you have faith in and or feel like they are hearing this urgency that you put forth in your music?

No. Honestly, no. When you understand slavery, colonization, 400 years of brutality to our minds in Africa, I don't expect anything to change in my lifetime. The way I look at the game is, the lives of my father, my grandmother, Martin Luther King, fighters who fought for emancipation of Africa and for global peace, for unity—without that, there would be no point in being alive. So you don't despair. You still have to find the courage to prepare yourself and try to help others as well. I don't just talk to the audience. I talk to myself as well, because this is what I feel. This is what I see.

You have to understand the characteristics of the characters who are in government and who surround us. They've gone through this colonial education, which is very selfish. It encourages a very selfish attitude. Mine, mine! It's full of greed. So I like to look at how Africa should have been. We had that kind of community set-up. We didn’t say "my." We said "our.” Our children. Because we know we have to take care of all the children. We say “our wives.” It doesn't mean you're sleeping with everybody's wife, but to have that sense of community. Our house. Our schools. Our hospitals. We never say "my."

So that attitude of the African culture and tradition has been taken away from us. And now we have this colonial setup, which is all about greed. Mine. You just want to grab everything and you never seem to get enough. No matter how much the leaders steal, it's never enough. You would think that one billion would be enough for two lifetimes, but they just grab and grab. The attitude of the education does not let us see pan-Africanism. We still look up to Europe and America. And we look up to the West, or the East now. We criticize ourselves, and bring ourselves down. We don't like our names. We don't like our culture. Education has taught us this. Education has taught us to hate ourselves. Our women go about with foreign hair. We send all our money to the East now.

When I was growing up, we even had a more positive attitude. In school, the girls used to make African traditional hairstyles. Now all that is mostly gone. We see the newscasters all with blonde hair, and you can't even tell them they look ridiculous, because then you are insulting them in a way. They don't see that it's so important for us to believe in ourselves, to love ourselves, and respect others. But this is the way my culture and tradition teaches me, and I tried to move more to that. But then when I see all this, I understand why we are the way we are.

Then we have religious problems. In Christianity, we have Baptists, Anglicans, Methodists, Catholics, Cherubim and Seraphim… We have so many branches. And they don't all agree. Then the Muslims have their own attitude towards what they believe should be our way of life. And in all this, we are talking about hundreds and hundreds of years that this has been imposed on our way of life.

Sometimes, when I want to be objective, it can really be heartbreaking. But then, one has to really understand where we are at. Do a little bit, and move. Because otherwise you'd probably commit suicide and be really desperate, overcome by sadness. Right outside my house, we haven't had good roads for 20 years, and everybody just thinks it's normal. The people live in poverty. The government keeps promising things. I've been talking all my life. It doesn't seem as if anything will change in my lifetime. As I said, I'm going to be 60. I've been playing music for now for 43 years.

People are agitating. They want change. So progress has been made. My father is still very, very relevant in the minds of people. There's a kind of balance in life today. It's not all full of negativity. It's just that I don't want to fool myself and think that a snap of the fingers will change anything. There is no magic wand is going to change where we are at today. Historically. Globally. And we're not talking only about Africa. You go to America and there are enormous problems. Go to China…

I like to see things globally. When I understand the human race, and our attitudes for thousands, maybe millions of years, the bottom line is: This is where we find ourselves today, and we can only keep on trying to enlighten ourselves and keep on talking about things that are important. Climate change. The next virus that might wipe the human race out.

It is so sad that government does not see when people agitate for a quick response to these kinds of things that could happen. They're always so slow, showing up in their big cars, with their security… Because when they find themselves in that system, they get swallowed by the negativity of that office. They have all the security. They snap their fingers and everybody's, “Oh, Mr. President. Sorry, Mr. President.”

The same people who begged us to put them into office, the minute they get in, we have to beg them to do their duties. Again, this is the style of government that the world shouts loudest about. But it's not really any different than any other part of the world. There's always oppression somewhere. Like I said, we just have to find positivity somewhere to fulfill ourselves to keep on living, to fight for the future of our children. So I never let that bring me down.

Wow. Well, I do see where the urgency comes from.

You listen to Made’s music, see Made’s progress; that some positivity out of the struggle to make the human race better.

Femi and Made Kuti (Photo by Sean Thoms)

It is hard to face that idea that you don't think you're going to live to see real change in your lifetime, but you have to keep trying. I think about our country. I'm a little bit older than you, and I see now that I grew up in a very unusual time, a time of social progress and hope. It's kind of a shock now to see us sliding backwards into racism and authoritarianism, losing ground, especially when, as you say, the world is facing such huge challenges.

I have read about your engagement with the police during the #EndSars movement. I spoke to a number of younger artists in Nigeria during that time, kind of probing them about their willingness to get involved in a cause like that. As you know, there's a whole narrative surrounding the young Afrobeats artists. A few of them are serious about presenting a serious message. I would put Burna Boy in that category. But it seems like a lot of them really aren't that engaged. They pay lip service to the legacy of Fela, but then go on singing mostly songs about love and money and sex and so on. The excuse is always that people don't want to hear about the problems they see all around them. They want an escape. You've heard this argument.

Yes, yes.

So what is your sense of the commitment of this generation of artists to messages of social engagement?

Well, at my age I wouldn't even delve into that topic with them or anybody. Everybody has their path in life. To choose the path Fela took, you pay a very high price. Nobody is willing to have their mother killed, or lose their life, or not be able to put food on the table. But he's still relevant 24 years after his death. I chose this path probably because of my upbringing. My upbringing wasn't about material wealth. My upbringing was pan-Africanism and global unity. I had to look for my path, not to just follow my father's. I didn't have a musical education so I had to strive to excel. But in my passion to excel, I always realized I was living in extreme poverty, surrounded by extreme poverty. And these are the things that touched me.

I knew that I would not get money from multinationals. They would never give me money. But I did believe in myself, that if I worked hard, I would still be able to produce good music. Probably I would get my break internationally, which I did. My Shoki Shoki album exploded. I'm still relevant in my lifetime. But the price, the energy… You can't tell anybody to go that path. This has to be their choice. I didn't encourage Made to take this path either. Because if anything goes wrong, you can't blame anybody. I can't play my father. It's my choice. I loved his life. I believed in him. I respect him. So it's my choice.

So when I'm dead broke, or things don't go like I want, I just go into deep thought. "How do I get out of this mess?” I practice more. I'm doing six hours of practice now. People say I look so tired. But I enjoy being tired. You see? I just wake up in the first thing I want to do is practice. When I go to bed, in my mind, it's just practice. I don't think first of the political message. I think of my profession, which is first and foremost I am a musician. I know there are hundreds, thousands of musicians working, and to be relevant, I'm going to have to be one of the best. I know there are thousands of saxophonists or trumpeters or composers, and I have to keep on working, because I'm at a disadvantage. I didn't go to school. So maybe the odds are against me, but that's my attitude towards life.

Now, I can't tell anyone to take my path. This is my choice. And I know what I have to do. I have my ups and my downs, and I have to find a way to lift myself up. I look at it as a game. You know that Stevie Wonder song “I Just Called to Say I Love You.”

Of course.

Many of us have used that phrase. But we're all so political, taking up arms and killing one another. So probably it's nice to have some variety, some stupid songs, senseless songs, love songs, songs that make us laugh.

They certainly have their place.

Femi Kuti at the Shrine (Eyre, 2017)

Yes. I mean there are songs that can be very serious. You don't want to have a serious day and then somebody is hammering it into your head. It takes a very strong mind to take that bitter pill again. So what I try to do is I put so much energy into the music and give them this sweet drink with the bitter pill. The bitter pill is the message, but then you can slow down. So I try to work that into my compositions. I understand that I'm just a medium that the higher forces use for this path I have chosen, which I must not abuse. I must understand that I'm not above what I'm doing. I'm being used for this and I have to respect it.

So like I said, I can't tell the young people what to do. I mean this music, the Afrobeats, it's very popular. They play it every day at parties, restaurants, everywhere. It's not what I want to do. I grew up with jazz, funk, classical music. I'm more of a meditative person than a party person. But it would be wrong for me, because I'm respected, to start to criticize, especially when I know the society we are all living in. Many of them have been at strong disadvantages from their youth, and they just find themselves when they hear this hit. You can't blame them. You can't tell them that they are not musicians. But I will always advise them because of the next generation. You can't call yourself a musician if you don't play any musical instrument.

Here, here.

You are an entertainer, and you have to understand the difference. If I want to find a bass player in America, I will easily find about 5,000 great bassists. It is embedded in the system, in institutions there. You don't joke as a musician. A musician is a musician. It is in the culture to practice and practice. In school you have teachers, you have competitions. We have to bring that attitude back to Africa, and this is where government comes in. This is where multinationals come in. What we should be doing is creating academies, putting people into music school and letting them know that the competition outside Africa is great. If you can't read, write, computerize your music, you are going to be lost. Because the older you get, the more stupid you are going to look. You can keep calling yourself a musician when you can't read, you can't write, you can't play any musical instrument.

You don't even write your music. You buy it from a producer. The producer who produces it does not become popular. You will become popular because you've got a gimmick in the words or something. I keep telling them that music is as serious as medicine or law. Everybody listens to music. The pilot listens to music. The doctor listens to music. The way we talk is musical. Making love is musical. So the composer has to put himself in that arena, to understand how important it is what he or she is doing.

But enough of me. You have questions for Made.

Made Kuti (Photo by Optimus Dammy)

I do. As a transition, I know very well that you had a difficult and complicated relationship with your father, and that you have approached raising your own kids in a rather different way.

That’s true.

So Made, when did you first know that you would be a musician?

Made Kuti: That's a tough question. I don't think there was ever a point where I decided I would be. My earliest memories are very musical, of me at the Shrine, watching my dad play, learning instruments. I think at first I picked up the trumpet. I was about 3 or 4. I asked him to teach me the sax at 8. And then I asked for a piano teacher at 10. And then I asked for a guitar teacher and drum teacher at 11 and 12.

Amazing.

My dad performed four times a week at the Shrine: Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Sunday. So my weekly life was very musical. And then I followed him on tour. I went to the studios with him when he recorded a few albums. So there was never a point when I made that decision. It was just the environment around me. I could've gone one of two ways. I could've rebelled against music, or I could've loved it, and I naturally gravitated towards a love for music. It was never a decision. It just flowed in that way.

It is incredibly impressive that you played all the instruments on your album. It's almost hard to believe, because it sounds so organic. It really feels like a big, tight band. But you are growing up in a very different musical time than your father or grandfather. What would you say are the influences you are bringing into Afrobeat that are unique to your generation?

Well, musically I'm of course heavily inspired by my dad, and Fela. A lot of the methods that they used to advance Afrobeat in their own very unique ways. We talked about my dad's energy. But there are also a lot of things he did on the Shoki Shoki album that I couldn't find anywhere else in Africa. It was released in 1998. That album is just like an endless source of ideas for me, not just musically but in terms of production quality. He was experimenting a lot with that album and then he allowed a lot of remixes of the tracks. So I really like where that went.

But I thought that the idea was to not replicate, and to find my own sound. That is something within music that I did make a decision to do, rather than following the ideas that were there, having Afrobeat live on in the way it did for Fela and my dad. I was using similar techniques, but I chose to do what you just mentioned, to navigate away from anything that was predictable.

The simplest thing I do, that is I don't compromise my ideas. I listen to a lot of music. I listen to Afrobeats, to a lot of classical and jazz music. I also listen to a lot of rock music, also electronic jazz. I have my interests. But when I have an idea and develop it, I don't let myself be worried or weighed down by the idea that it's not authentic compared to what Afrobeat has been. When those ideas are different, or the sound is different or the melodies are different or the structure is different, when those ideas come, I feel them, and I make sure I go in that direction of change. So it's more me just doing the things that I enjoy, rather than sitting down and trying to be very deliberate about doing something different. So it's the decision to not filter my ideas, especially when they sound like they're not specifically Afrobeat.

That's cool, and I hear that in your music. Your father demonstrated, and you demonstrate even further, that Afrobeat has a lot of musical possibilities within it. It's not something that has to be exactly the way Fela did it. There are a lot of bands that do that, and that's fine. But you guys are showing that this is a genre has a lot of flexibility. It has already absorbed a lot of things. From the beginning, it was a mixture of highlife, funk, Nigerian traditions... But it established a sort of core identity, a very strong identity, so that now you can do a lot with it and not lose that identity. I think you really show that on this album. I'm intrigued by one largely instrumental tune,“Higher You’ll Find.” I hear in that song drum and bass and techno elements, but you still feel that it's Afrobeat. But let's talk about a couple of your messages. The song “Young Lady” addresses the situation of university professors rewarding female students with good grades for sexual favors. It’s very powerful. Talk about that song.

The song was inspired by a great BBC documentary by Kiki Mordi and her team. It was about sexual abuse by lecturers to their students in universities in Lagos and outside Lagos as well. It's very commonplace. It's so common that it's hard to meet any girl, any lady or woman, in any higher institution that hasn't encountered it herself or know someone who has encountered sexual abuse. It is so common that now a lot of women deliberately choose that route because it guarantees good grades and certain success in higher education. So they choose to market their body because they know they will receive certain profitable consequences from it. The real problem, I think, is one there is no route other than that. Sometimes people do pass on their own.

I hope so.

But often they are not given their accurate grades because they haven't satisfied the lecturer in the way that he has demanded. And if you don't have any power behind you, like a powerful family or money or a name, access to certain influential powers in Lagos, it's very easy to be manipulated, because you have no way to properly defend yourself.

The videos I saw in this documentary were gruesome. A student would enter with a secret camera to meet a lecturer, and he would ask her about how she looked, and see if she's interested in coming to this group where the lecturers go in the school with these underage girls. He kept making sexual remarks about her appearance. “Ah, You look really beautiful today. How many guys have told you how beautiful you are?" This is where the lyrics for "Young Lady" came from.

I think it hit home for me because I knew someone who was going through this personally at that time. For this young lady, it wasn't just about her education. It's everywhere now. It's so easy for men to manipulate women in Lagos because power and influence dominate everything else. There really isn't law and order. To get away with murder in Lagos is quite easy. If you kill a person, and then you bribe a person or settle with the family, you are almost guaranteed not to go to jail. There's no proper justice system for criminal activity or any kind of crime. So sexual abuse is kind of brushed under the rug. It's the least important thing in terms of crime. Because there is so much crime and so much disorder. You can kill. You can rape. You can steal.

People plan robberies in apartment complexes. They rob houses around the neighborhood, so it doesn't seem like a direct attack, but everybody knows it was that neighbor who did it. It's so common. It happens to so many people.

And also there are some very odd, old cultural values that are taking precedent where human life is not regarded. For example, when a king dies, he is supposed to be buried with sacrifices. A lot of us have moved away from that kind of mentality. We understand that culture exists. We understand that every ethnicity has done things in the past, and we have to grow up and understand why those things are wrong. But there are people who still hold these values so strongly. If they announce this cultural festival for the death of a king, and you are on the road at the time, if you are a woman, they will cut off your head and bury you with the king's body. Once they stopped us just like that, but luckily we got away because my dad was in the car.

That's incredible.

If it had been a different day and I didn't have my dad with me, I probably wouldn't be here today. So that's not a traumatic experience, but it's just one of the things that fuels the anger that my dad speaks so much about. The other day a woman was burned alive in the north because she said something sacrilegious. And then there was another musician, a sound engineer, a couple of weeks ago, who was beaten and burned alive as well. This was a district in Lagos, Lekki, so this is the rich district. Black men burned a sound engineer alive because somebody that was coming to a show where he was going to engineer punched one of them because he didn't want to pay an extra hundred naira. There were police cars driving past the scene, and nobody did anything. So today there's a protest happening about that incident. But it's so commonplace. Murder is so commonplace. When this happened, it was just another day in Lagos State. So “Young Girls” is about sexual abuse, but it's also about how easy it is to get away with crime in Lagos.

Made Kuti (Photo by Optimus Dammy)

Let me ask you about another song on the album, the one where you sample the speeches that your father gave in a public setting. The song is called "Blood." Tell me about that song.

That was coming from my fear of a violent revolution in Nigeria. My dad and I were speaking about how on edge the country was at the time, and any small spark could really lead to a catastrophe. The anger people were feeling, the disorder in everyday life… It's weird how we get by, because nothing seems to work properly. The people who are down trodden, the receivers of the majority of exploitation by the government and people in power are of course the vast majority. So we were wondering what it would take for them to finally say, "Enough is enough."

So then I was wondering how we got to this point. Of course there was the colonial era, then there was the euphoria after independence when it seemed like we were going in the right direction. Naturally there were challenges we were going to face, having hundreds of ethnicities put together in a very weird colonial structure that was supposed to function with so many people speaking different languages and having very different religious beliefs. But the challenge was to at least create a decent economy and a landmass for people to survive in. But here we are. Every day it gets worse. And it really does get worse every single day. However bad Nigeria was last year, it's worse this year.

My dad always uses the currency as an example. At one time it was two dollars to one naira. And now it's about 600 naira to one dollar. The thing is in Nigeria nothing ever gets better. Nothing. Nigerians are not used to seeing improvement in their lives and their surroundings. They are not used to progress.

I was thinking the other day how important it is to have an idea of what your goal should be before working towards that goal. So I posted on Twitter, "What is the Nigerian dream?" Ninety-nine percent, everybody except about two people replied that the dream is to run away from Nigeria. So Nigerians don't even believe that there's any point in saying. So if you have a conversation with the average Nigerian, this idea is that this is not the place to be.

It's not like Americans saying I have to go to Canada because America is getting really bad. It is always the case here. Off the top my head, of all the people I know, less than 10 people if I asked if they had the opportunity to leave permanently would choose to stay in Lagos. And that breaks my heart.

That is sad.

It really is. It was sort of a rhetorical question when I posted it on Twitter, but when I saw the replies, it made me so sad. To think that the majority of us don't even want to be here.

That speech in the song was taken from my dad's protest during the fuel subsidy protests. And that again was another form of Nigerian scam. They didn't tell my dad that the people that were organizing that protest were actually part of the opposing party in a bid to target the politicians involved at that time. He went there because he genuinely cared about the fuel subsidy. But he didn't go again after that day because he realized that talking about people from the A.P.C. [The All Progressive Party, current President Buhari’s party] that were stealing from the government put him on bad terms with the people who were organizing the protest. As soon as he mentioned those politicians names, they took the mic from him.

So even when you think things are progressing, with masses of people who genuinely seem to care about the direction Nigeria is headed, if you investigate, there's a small minority of people who manipulate those people to do something for their agenda. There's nowhere to look that is positive. There is nothing that works. Nothing works in Nigeria. Education is bad. Healthcare is bad. My brother told me about one time he visited the general hospital and he just saw bodies on the ground. These are things that we just accept as normal.

My dad went to the north for a campaign once, and he saw mass malnourishment. Lagosians really tend to believe that Lagos is Nigeria. They don't understand just how small we are, and the mass of hundreds of millions of Nigerians who are around us. And Lagos is supposed to be the most developed state. That is really scary. My dad saw a malnourished mother feeding a malnourished child, and he said there was just one water source for all the people in that territory. The cost of the trip to take him there to create awareness instead of solving their problems was 2 million naira. That's about $4,000.

So the song "Blood" was me worried about a violent revolution because no matter how you look at it, it doesn't seem like Nigeria can be solved peacefully. I wanted to believe that with the right education, with the right mindset, and with the right people, not in power but in leadership positions that really care about the Nigerian identity and the African identity and think progressively, I really think, like my dad said, it all starts with education. If we are educated to know how we got where we are, then I think we can at least discuss peaceful means of progressing forward. But Nigerians don't even learn about Nigeria. I was never taught history. I had to learn it myself.

Made Kuti (Photo by Ifeoma Kalu)

You had some good teachers in the family.

Exactly. But of course I am a minority. We speak to people about the colonial era, and they know nothing about it. And about pre-colonial Africa, they definitely know nothing about that. Nigerians believe they are inferior as well. A lot of people believe this is like this because this is how we are. And religion fuels that idea. All that they worship, and all the deities they present are white and very Western, with very Western attributes. People frown upon themselves and they get that inferiority complex maximized through a lack of self-awareness. That's what "Blood" is about.

That is heavy. You say that nothing works in Nigeria, but one thing that does seem to be working in Nigeria is the entertainment industry. From our perspective, it seems that Nigerian musicians are taking over the popular music landscape worldwide. Burna Boy just sold out Madison Square Garden. That must say something about something working in Nigeria. This is your generation. What’s your take on all that?

I feel like it's there in what you said. Burna Boy, Davido, Wizkid, CKay, Tems, Yemi Alade, Tiwa Savage. I don't think in terms of international success there is anything more than about 11 Nigerian musicians. If we look back into the industry, in Lagos alone, the industry doesn't really exist. So for example, an industry is top to bottom dependent on a means to first learn the field of study. So if you are a musician in Nigeria, there is only one place you can get a proper, even reasonably decent, education. It's a very small building, the Muson Center. And that's about it.

My friends’ musical courses in university, they say they've never seen a teacher playing an instrument. They have a teacher, but they've never heard him play. So education is busted. There's no means to learn. A lot of us are self-taught. And all my friends, the people who join my band, my musicians, everybody is self-taught. There should be a decent work environment and policies in place to protect musicians and their rights. It doesn't exist in Nigeria. There's no copyright protection. There’s no intellectual property. If somebody steals your idea, they steal your idea, and that's that.

The society is actually so unaware of copyright that if you steal someone's music, they can actually praise you for making it better than what it was. So the industry itself is functioning on one leg. Nigeria's current industry is only what it is because the songs are relatable. They sound good, and the people that have invested monetary value into it have done it well for those individuals. But the industry itself, and the way an industry is supposed to function? No. Schools should be able to punch out highly exceptional musicians year in and year out. And they should be able to come out knowing that there are jobs for musicians here and there, maybe in bars or in churches.

I don't think we have a band in Lagos, like a big band, like a national band. There's the London Symphony, the Philharmonic. We have nothing, no national band.

What about the Afrobeat bands? It seemed like Burna Boy had quite a good band at that Madison Square Garden show.

Other than the Positive Force and my band, and Seun Kuti’s band, my uncle, I don't think anybody travels with musicians. I think Burna Boy uses in-house musicians. I know the composers, the band in the U.K. That's what they use when they travel to Europe. I think there's another band for use in the States. I don't think anybody flies a Nigerian band anymore that I know of. It is just us that travels with Nigerians. And the argument is, "Why should they?"

It is expensive.

And the music does not really require it. The beauty of it is its simplicity. Wouldn't you just rather use an American Black drummer than fly in a Nigerian drummer? Right now I know that it's only the three of us who fly with Nigerian musicians.

But back to what you said about the content, it's exactly how my dad explained it. It's a challenge every day where people have to find meaning in their lives by themselves. So if you want to be a musician, that decision is already seems like a mistake. Because there's no proper avenue for success for musicians, so if you make that choice, you're deciding to go up against all these challenges and lack of opportunities. So if you do that, and you decide that the only way to put food on your table is to make heavily commercial music, as you said, that is not representing Fela in any way. It's about sex, it's about money, it's about drugs.

What the concern I think should be is not so much what the musician is doing, or even how the society perceives that music. While that music is of course the most popular, there are still a lot of musicians who make for a conscious music. They just don't get the attention that they deserve for it. So my dad has been playing at the Shrine for some 20 years now, and within this year, even within a space of about 10 years, I think he's had about 10 shows in Lagos, other than the Shrine.

That says a lot.

It's more a reflection of the society and the culture that the people are practicing than the musicians themselves. So the people who are in this predicament, the musicians, know that they are living in a very corrupt society and that in order to make ends meet is almost impossible, so why would they choose this value over that value? Why wouldn’t they value something that is significantly more shallow over something that might be a lot more necessary to the society. So I think the musicians are doing what they need to do to put bread on the table. And musicians like myself who choose to go in the other direction have done so because they can't stand the other choice.

It's not that I think that the other choice is bad, I just cannot do it. Because I'm so involved professionally in the reality—I don't really like the term “struggle.” I prefer reality rather than struggle. I can't pretend that it doesn't exist. Like my dad says, a lot of these people don't write their own songs. I think if you're involved in the compositional process of something, you put a lot of personal care into the things that you want to reflect yourself and your thoughts and your work. So maybe it's because we are composers that we treat it differently. Whereas if somebody gives you a beat and just says, "Make a gimmick on top of it,” you can make a gimmick on top of it because you know that that's all it takes to be successful.

So I just think that like my dad said, you have to have enjoyment of something, but you can also have enjoyment and seriousness at the same time. If you go to an Afrobeat concert, the lyrics are very serious. But the music is so spiritual and lovely that you almost face the challenges in a very positive way. Yeah, there's no life, there's no water. But you’re singing it.

I love that idea that you can put a tough message in sweet music. I always go back to Bob Marley: “Total destruction the only solution," and it's one of the happiest songs you can imagine.

Yes, my dad says taking the bitter pill with a sweet drink.

That's it. So let me ask you a practical question. You have your own band, and I assume it's a large Afrobeat band. What are you going to travel with on this tour?

Well, for the American tour I'm playing with my dad’s band. I cannot afford to travel with my band.

That would be a lot of people.

But the idea when I start traveling by myself is to take everybody. As long as the tour can afford it, I would rather take musicians from Lagos. Of course, there is my dad's experience, and Fela’s experience, and a lot of Nigerians’ experience, of musicians running away on tour.

Yes. That certainly has happened. And given the response to your Twitter question about the Nigerian dream, you have to expect that.

But like my dad says, you have to fight the fight knowing that you might not win in your lifetime. You have to be able to accept this if you care about something. You have to play your part and believe that your part should be done enough to continue the fight. If you feel like it should start and end with you, it's almost a selfish perspective. You have to take your place in the entire flow.

Tough wisdom there. It's a very good to speak with you, Made. I look forward to the concert, and to speaking more in the future. Once again, I'm so impressed that you have learned to play all those instruments so well, especially being self-taught. That's just extraordinary.

Well, I’ve had a lot of assistance. For example, my dad started me off on sax. But I taught myself bass. I learned a lot from watching my dad’s drummer.

You have had good models.

So many Nigerians have really just had no choice but to pick up something and try to figure out how it works. Even to repair an instrument is almost impossible in Lagos. To find a repair shop on tour is so easy no matter what city we go to. Whereas in Lagos, there are about two guys out of 20 million you can go to to fix your sax.

Well, there's an opportunity there. I imagine you're hitting the road very soon, any day now.

We have an important show this Sunday at the Shrine. It's the Father and Son Concert. It's the first time my dad and I are playing properly with two separate bands at the Shrine.

Fantastic. Wish I could be there, but I look forward to seeing you in New York.

Thank you.