Man Ray, an artist who has long permeated our visual and popular culture with singular, iconic works like an iron bristling with tacks or a woman’s back bearing the sound holes of a cello, is the subject of a fascinating new exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Titled "Man Ray: When Objects Dream," the show offers a fresh perspective on one of the 20th century’s most inventive and boundary-pushing artists by focusing on what is arguably his most groundbreaking contribution: the Rayograph. A unique collaboration between The Met’s Modern and Contemporary and Photography departments, the exhibition delves into the formative years of Man Ray's career, from 1914 to 1929, using the Rayograph as a "wonderful through line" to connect his prolific work across painting, sculpture, film, and assemblage. Co-curators Stephanie D’Alessandro and Stephen Pinson have structured the exhibition not just to display these works, but to unravel the very process of artistic discovery, inviting visitors to participate in a pivotal moment of art history.

Man Ray was one of the first true "multi-hyphenate" artists, constantly experimenting and refusing to be confined by a single medium. He found inspiration in the most common, everyday objects, transforming items like an eggbeater by hanging it on a wall, lighting it dramatically to create anthropomorphic shadows, and photographing it to create the works L’Homme (Man) and La Femme (Woman). In doing so, he elevated "trash" to the level of art and deliberately engaged in the heated debate of his time over whether photography itself could be considered a fine art. This relentless spirit of experimentation and transformation is the core of the exhibition, which charts his progression from painting and collage to camera-based work and, ultimately, to a photographic process that eliminated the camera altogether.

Related article - Uphorial Radio

Man Ray: When Objects Dream

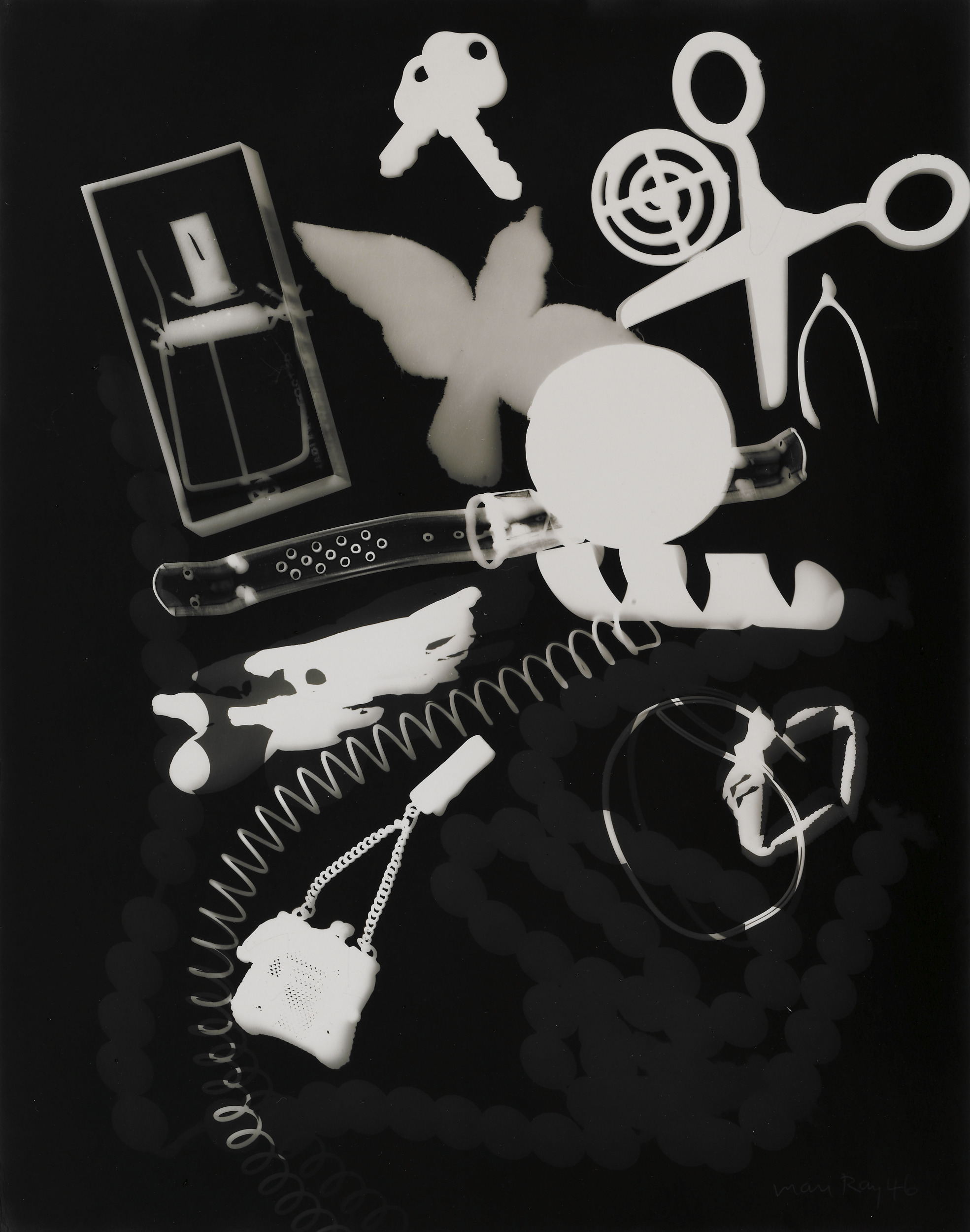

The exhibition's journey begins where most people would have first encountered the technique: with Champs Délicieux, an album of Rayographs published in Paris in 1922. Man Ray himself described this new method as the "climax" of a decade-long search. The images are deeply mysterious; the more one looks, the more enigmatic they become. Viewers might recognize a toy gun or a key, but the interplay of light and shadow, where space is as potent as form, defies simple interpretation. A Rayograph is created by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper and exposing it to light, a technique nearly as old as photography itself. However, in Man Ray's hands, it became a tool for profound artistic expression. The brightest white areas are where objects completely blocked the light, the deepest blacks are where the paper was fully exposed, and the marvelous gradations of gray reveal how he masterfully manipulated transparency and movement during single or multiple exposures.

The heart of the exhibition is a quiet, contemplative space with black walls, presenting about 60 Rayographs gathered from collections across the United States and Europe. This central gallery allows for a slow, immersive viewing experience, revealing the technical marvels behind what began as an accidental discovery. As the story goes, Man Ray stumbled upon the process by mistake in his darkroom, yet the resulting works are anything but quick or simple exposures. His fascination with certain motifs, such as the banjo—an instrument he likely played—is evident in his repeated explorations of the object, each time pushing the technique further to create elegant, beautiful, and mysterious compositions.

The exhibition compellingly argues that the Rayograph was not an isolated experiment but a central force that re-energized his entire practice. After a period in 1922 where he made perhaps a hundred Rayographs and famously gave up the "sticky medium of paint," he returned to the brush in 1923 with a new perspective. The curators showcase a series of small, often-overlooked paintings from this period that have been described as "painted Rayographs," demonstrating clear formal similarities in their construction. Many of these paintings, now brought together for the first time since 1926, show how his experience with camera less photography informed his work in oil paint. Even his most famous photographic masterpiece, Le violon D’Ingres, was enhanced by this innovative spirit; he called it a "photo Rayograph," having used the technique to create the cello’s sound holes on the back of his muse, Kiki de Montparnasse.

The exhibition concludes by looking at Man Ray's work with Lee Miller, an American model who arrived in Paris in 1929 wanting to "make pictures," not just be in them. She became his apprentice, studio partner, and romantic partner, and together they explored the technique of solarization. This process, which creates a beautiful halo-like contour line around subjects, produces mysterious and magical images that make figures appear almost cut out and pasted onto the background. For a time, this darkroom collaboration with Miller replaced the Rayograph as his main creative outlet. Yet, the exhibition brings the narrative full circle, closing with a Rayograph Man Ray made in 1959, decades after he had seemingly moved on, underscoring the technique's lasting significance. In an age saturated with images that can easily fool us, Man Ray’s work serves as a powerful reminder of the boundless possibilities of an image and that there is always more to the story than meets the eye.