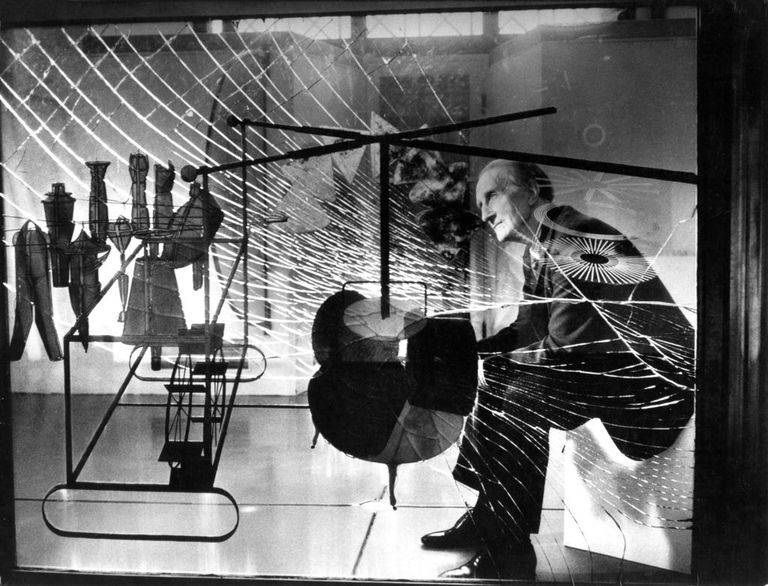

California’s surreal 1960s truly began one Los Angeles morning in '63, when pioneering dadaist Marcel Duchamp met stark naked Eve Babitz. Duchamp had by then semiretired from art to play chess. Babitz was just beginning her career as a cultural provocateur. Here, she recalls the story behind their encounter, which changed her life and her city forever. This article originally appeared in the September 1991 issue of Esquire. It was reprinted in the April 2018 issue. You can find every Esquire story ever published at Esquire Classic.

“His position was extraordinary,” my wonderful friend Walter Hopps informed me. Walter was the One, when it came to all this—long ago, when hardly anyone knew—who knew. “One way to look at it—these things are never set in granite—is that Picasso and Matisse fulfilled the dream of the nineteenth century, and the two artists who hold the really extreme positions unique to our time are Duchamp and Mondrian. Art for the mind and not for the eye. The irony is, Duchamp did so many beautiful things. But not just stuff you decorate walls with. His great contribution to art was elsewhere.”

Jim Morrison Wasn't Cool, Said Eve Babitz

Meaning that in the nineteenth century a urinal could only say—if it could say anything—“I’m a urinal.” But after Marcel, a urinal could also say, “I look like a urinal, but Marcel says I’m art.”

“In other words,” Walter may or may not have ended, “Duchamp playing chess with a nude in a photograph may be art.”

Of course, if you’re the nude, being “art” seems beside the point. At least with the Naked Maja, you could be airbrushed and posterity would think of you as perfect, whereas on that day, sitting naked in the museum, having to play chess with someone who hardly spoke English and was so polite he pretended that the reason he’d come was to play chess—well. And afterward, when the photograph began showing up on things like posters for the Museum of Modern Art, and Nude Descending a Staircase became almost interchangeable with Nude Playing Chess, and Duchamp being so immortal, I just wasn’t sure I wanted to be identified. Maybe it would be better to be “and friend.”

“Hey, Eve,” Julian said, grinning. “Why don’t I take pictures of you nude, playing chess with Marcel Duchamp?”

On the other hand, if they’d asked anyone else—or if I’d chickened out and some other woman was immortalized—then, hmmph…. Recently, when a woman called and said she was doing a book on Duchamp on the West Coast and could she please use that picture, I said, “You’re not going to use it on the cover, are you?” But when I found out the cover photo was to be of Marcel alone, I felt insulted. Mixed emotions hound me after nearly thirty years of mixed emotions. I want to be on the cover, immortal, but I don’t want anyone knowing it’s me. Except my friends and people who like it.

Otherwise, I’ll just be “and friend.” Anyone who thinks the nude should have been thinner, or in any way different—to them, I’ll be a floating image of “elsewhere.”

Immortality or no.

In the 1913 Armory show in New York, there was a scandal over Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. If you look at the picture today, you might ask yourself—Pourquoi? It’s not as though it’s a photograph or anything naked you could see. It was so diffracted and cubistic, who could tell? Maybe it was a scandal because people had to take it on faith that there was anything there at all besides olive-green, beige, and black corners that may or may not have been a staircase. That painting, however, made Duchamp famous and laid the way clear for twentieth-century art to be not what it seemed.

The interesting thing about that painting is that it was bought (for $350 or so) not by some hip New Yorker but rather by a print dealer in San Francisco, who put it in his office as a publicity stunt.

In Hollywood, there was a genuine collector couple, Walter and Louise Arensberg, who amassed Duchamp works as though Los Angeles were a totally cultivated city where you’d expect people to know what was happening artwise in the twentieth century—like Gertrude Stein and her brother, who knew what was what practically before anything was anything. Only the Steins were in Paris, where art was in the air, whereas the Arensbergs were in Los Angeles, where if you could draw, you’d be good if you were Walt Disney.

Los Angeles was a hick town with a vengeance, artwise. If you judged it by the L.A. County Museum, or by its nowheresville galleries, or by its public philanthropies like the Huntington Library, where they kept all the Gainsboroughs and Joshua Reynoldses, the place was hopeless. It was so impossible that the L.A. County Museum didn’t admit any art from Los Angeles. In the Fifties, my mother once picketed the place with her friend Vera Stravinsky, just to call the museum’s attention to the fact that nobody from L.A. was inside. The museum relented and held a contest for local artists, promising to hang the work of the winners, and my mother won for a line drawing of old houses on Bunker Hill.

New York was ablaze with glamorous guys like Pollock, Rothko, De Kooning, and Motherwell, but in L.A., even if all you wanted to see was French Impressionists, you had to know Edward G. Robinson.

My parents were sort of a team to combat L.A.’s hickness, and in the Fifties, they took it upon themselves to have poetry and jazz things in our living room. And although I liked only Kenneth Patchen and thought everyone else was long and boring (being a teenager who preferred Chuck Berry and Elvis), I could see that the adults were completely elated, and I could see the point in being a beatnik if that’s what James Dean was supposed to be.

My father was a violinist with taste and determination, and he and his friend Peter Yates began something called Evenings on the Roof atop Peter’s house. There, slick studio musicians who could sight-read anything performed never-before-heard works by, say, Stravinsky or Schoenberg, who both lived in L.A., where the Philharmonic rarely played anything newer than Brahms, and even that nobody went to.

In 1937, when my father was still playing in the L.A. Philharmonic, Stravinsky came to conduct. And Stravinsky so loved my beautiful and funny father that later on he became my godfather, and his wife, Vera, and my mother were great friends. My parents and Stravinsky and Vera used to go see Jelly Roll Morton or mariachi bands, or my father would jam with Stuff Smith in dives—they double-dated, you might say. Not that Vera ever got over there being no clothes in L.A. or anything else to remind her of Paris, the only city, in her opinion, where anyone sensible would want to live. But Stravinsky loved the climate, and after World War II, when everyone else who had been on the lam (like Brecht and Thomas Mann and Jean Renoir) returned to Europe, Stravinsky stayed—he wasn’t going anyplace it snowed ever again.

So I grew up listening to adults complain about L.A. and its hopeless cultural condition, but not in that condition myself, being surrounded by such high magic.

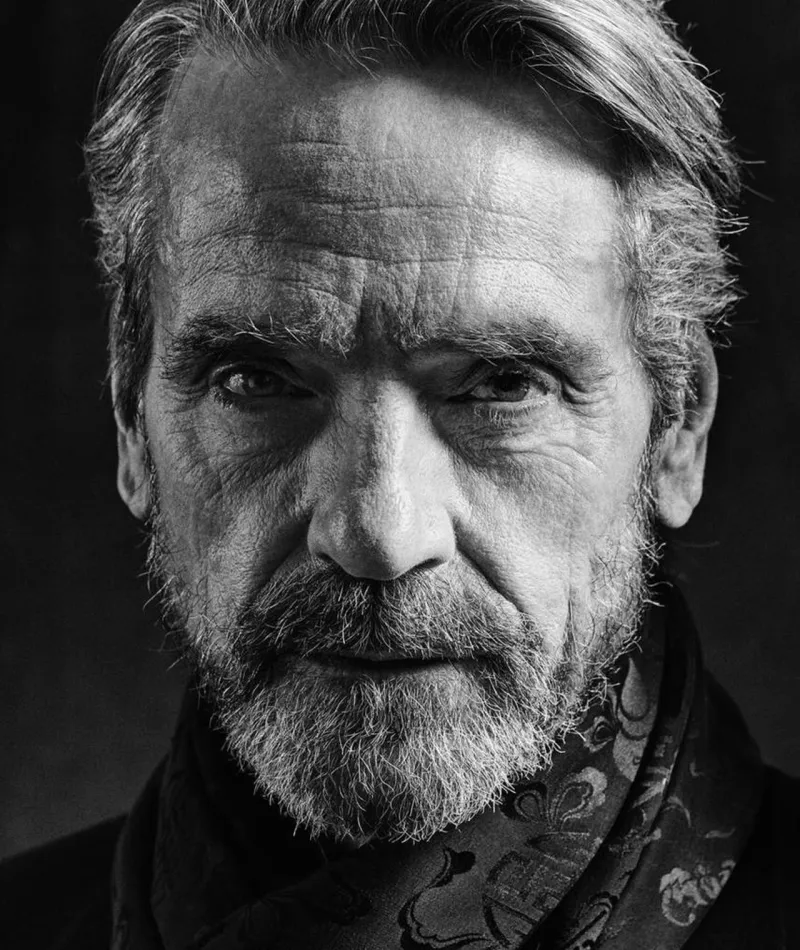

Meanwhile, Walter Hopps was growing up a whiz kid from Eagle Rock, in a program in high school for the truly brilliant, and once a month they went on strange field trips, one of which, in 1948, changed his life forever. Before that (he was only fifteen) he was supposed to become a doctor—he came from a family of doctors, his mother and father were both doctors, his grandfather and grandmother were “horse-and-buggy” doctors in Eagle Rock, his great-grandmother was a doctor! But then one day he was taken to the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg.

“And so you saw the Duchamps there?” I asked. “And did you get it? I mean, about Duchamp?”

“In a word?” He laughed. “Yes.”

“So it changed your life?”

‘The whole core of my thinking was shifted very particularly within a year,” he said. In other words, he started hanging out with low-life types, going to jazz joints with fake ID, and mingling with Wallace Berman, who wasn’t yet an artist but more just a hipster.

In 1957 or so, when Walter opened the Ferus Gallery with the artist Ed Kienholz, he finally dropped out of school. He had already opened three galleries by then, and he was only twenty-four. He still looked like a doctor, and he had such a bedside manner he made people feel better just by entering a room. And though he talked all the time, he gave the impression of utter silence.

Everyone else in the art world, or what little art world there was in those days, may have seemed far-out and beatniky, but Walter, in his neat, dark American suits with his white shirts, ties, pale skin, and blue eyes behind black eyeglass frames, seemed too businesslike for words. It was as though someone from the other side, the public side of L.A., had materialized on La Cienega, on our side, the side of weirdness, messiness, and art.

One of the first shows they had there, a Wallace Berman exhibit, got busted for obscenity, which got things off properly and sealed our faith in Walter. If someone so classic-American was willing to let a crack of light into fluorescent Los Angeles, a crack of darkness…. Plus, he had such a convincingly deadpan delivery that rich older ladies might actually buy this stuff.

In 1962, when I was nineteen, I was going to L.A. Community College (because you could park, unlike at UCLA). One day a girl came up to me, told me her name was Myrna Reisman, asked if Stravinsky was my godfather, and when I said yes, she said, “Great, I’ll pick you up around eight.”

SOURCE : esquire