“This wasn’t planned,” remarks Emeka Ogboh.

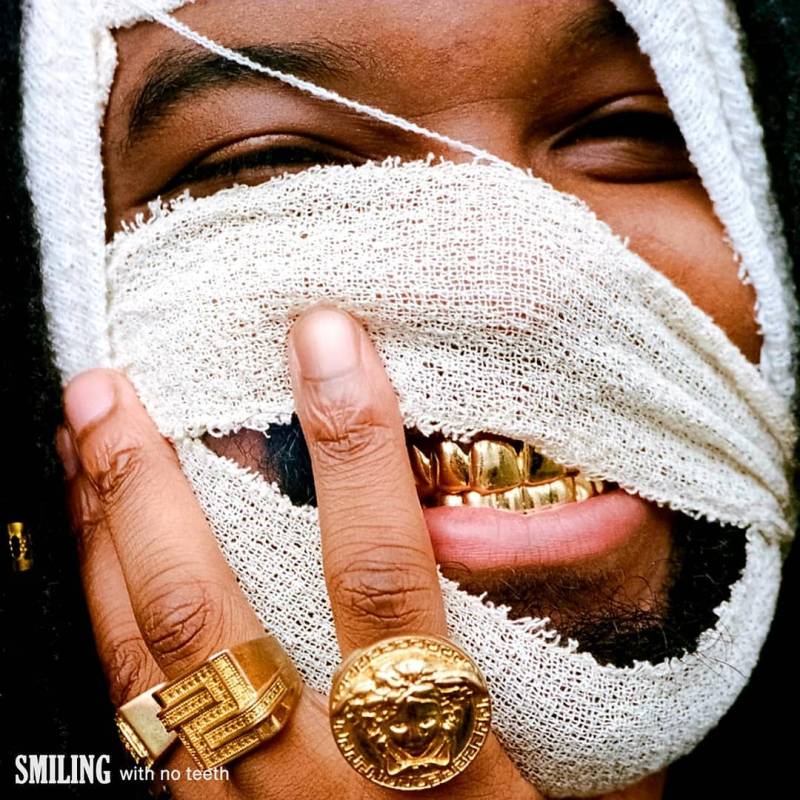

Emaka Ogboh has managed the leap from acclaimed sound installation artist to celebrated experimental music producer isn’t as hard to get your head around as you might imagine, even if he does admit that becoming a musician was never his intention. It’s a phrase he repeats often as we meet ahead of the release of his second album (and the first for his recently-inked label, Danfotronics), 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E.

Despite his nonchalance, the highlight reel covering his career so far features a fantasy wishlist of both highly-regarded art institutions and record labels, including Ostgut Ton’s ambient sub-label A-Ton, which released his 2021 debut,

Considering that Ogboh’s second album has only been in his purview over the last year, 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E is an example of the spoils that may lie on the other side of what he calls “a pile-up of pressure”. In his case, the weighty expectation that followed his unplanned debut and its unanticipated success. But that pressure has given way to evolution.

Read Also: Post Humous Birthday: Nelson Mandela! 5 Quotes He Said That Still Ring True Today

Throughout 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E, the sounds of Ogboh’s signature field recordings and interviews, captured in the bustling streets of Lagos, Nigeria, serve as narrator, temptress, guide and antagonist, through musical moods that range from calm introspection to jaw-clenching tension.

The album’s subtle atmospheres and textures sit in contrast with Ogboh himself, whose physical height and charisma are only magnified by the setting in which we meet – a pristine yet featureless café in the west Berlin neighbourhood of Charlottenburg. But for all the twists and turns in Ogboh’s life, there is a common thread in his story: taking the road less travelled.

How the Journey Started

In 2008, he left Nigeria to pivot away from graphic design and become a student of multidisciplinary art at the Fayoum Art Center in Egypt. He then moved to Berlin in 2015, and after finding himself regularly surrounded by art-world types, began to pursue other interests: “I stopped going to art openings,” he laughs.

“Instead, I’d go out to craft beer tastings.” Unsurprisingly, all of this exploring generated new and unexpected creative paths. “A lot of my work has to do with migration or movement of people,” he explains. “I try to be more mindful about what that intersection could be, both in my career as an artist and as my hobby.” Ogboh embarked on a beer-brewing collaboration connecting Germany and Nigeria, which became part of a broader art project. The recipe he used was created using honey from linden trees that line the promenades of Münster.

“During the fermentation process, we attached transducers to the fermentation tank, and played my sound installations through it,” Ogboh explains. “For the period of the fermentation, the yeast is vibrating to the sound of Lagos.”

Ogboh’s musical practice stems from exhaustive field recording sessions in which he captures the sounds of Nigeria’s capital city.

With titles like Lagos Soundscapes and Lagos By Bus, his installations have transported listeners to the city via the sounds of bustling streets, the sing-song calls of food vendors, and the narratives of its taxi drivers in the creolised language of Nigerian Pidgin.

In the years leading up to 2020, he exhibited his experiential sound installations at the Venice Biennale, documentary in Athens, Brooklyn Museum and London’s Tate Modern. But when the world locked down during the first year of the pandemic, Ogboh was contacted by the Boros Collection – a famed private museum of contemporary art housed in a WWII bunker in the centre of the German capital.

They invited him to contribute a piece for an exhibit showcasing Berlin-based artists, in collaboration with and presented by the city’s even more famous cultural behemoth, Berghain.

“I’m not one of those artists that always has a clear vision of what I want. I like going with the flow because it’s going to naturally develop and lead me somewhere”

When the Boros Collection asked how Ogboh had been passing the time in lockdown, he gave the near-universal answer: “I said to them, ‘Mostly on the couch watching Netflix.’” But he also revealed that he’d been privately experimenting with music production over the last couple of years. For Ogboh, learning to use Ableton was an organic expansion of his experiments in sound design – a means to an end. Previous attempts at collaborating with composers had resulted in frustration, due to the realities of filtering his own ideas through the knowledge and sensibilities of others. “I needed to learn how to use these tools, because I’m not one of those artists that always has a clear vision of what I want,” explains Ogboh. “I’m abstract. I like going with the flow because it’s going to naturally develop and lead me somewhere.”

This DIY approach manifested in Ogboh pressing a small number of his solo compositions onto vinyl in 2018, as part of an exhibition in Paris. After hearing Ogboh talk about the record on their call, the Boros Collection expressed their interest in using the music in the installation staged at Berghain and the record label attached to the club, Ostgut Ton, also took notice. They asked him to submit a track to be included on a compilation for A-Ton. He sent them his one finished record.

“Ostgut called me,” says Ogboh, “They were like, ‘We’re just checking, are you saying you didn’t release this album before?’ I’m like, ‘… No.’ They said, ‘OK, we want to release the whole thing.’” Ogboh admits that he was sceptical about entering the world of music. “It took a while,” he says, “but I eventually agreed.” The enthusiastic response to Beyond the Yellow Haze still surprises him now, a year after its release. “The streams on YouTube were insane!” he recalls, chuckling. “In a month, I was up 15,000 listeners from having single-digit listeners before. I hadn’t even been thinking about making music. I was just having fun.”

While he does have plans to eventually incorporate 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E into a video installation, this is a unique moment in Ogboh’s career. It’s the first project of his to emerge that is, primarily, a piece of music. Like his installation work, 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E is concerned with what our corporeal data can reveal to us as we attempt to navigate a supposedly post-colonial world. Beyond the Yellow Haze simmered and pulsed while voices rang out, horns honked, raindrops splattered and car doors slammed, all folded into nebulous rhythms. 6°30′33.372″N 3°22′0.66″E, however, is more focused and specific, in both sounds and the location that inspires them. Just like the GPS coordinates from which its name is taken, the album is firmly anchored in a place.

That place is Ojuelegba, a region of Lagos notorious for its nightlife and red-light district, concentrated around a street named Ayilara. Ojuelegba has been immortalised in song by two of Nigeria’s biggest musical exports: Fela Kuti, whose 1974 track Confusion Pt. 2 depicted the chaos of its roadside markets and traffic jams, and Afrobeats titan Wizkid, who released Ojuelegba in 2014 complete with a video of himself as a passenger in a danfo, one of the city’s unofficial yellow public minibuses.

The focus of Ogboh’s latest work focuses on more than just the neighbourhood’s vice and infamy, and explores its mythical significance. “Ojuelegba is this intersection of four routes,” he says. “In Yoruba mythology, intersections are considered spiritual places, so before the infrastructural development around this bus station kicked it out, Ojuelegba used to house the shrine of the god called Eshu – the god of confusion.” According to Ogboh, through the binary designations and misinterpretations of white colonialists, Eshu became mischaracterised as an evil figure. “The closest the English could come to Eshu being ‘mischievous’ or ‘naughty’ was the devil, which is a misnomer,” he continues, “but people still believe the presence of this god is there.”

The narrative of the album continues Ogboh’s study of the oral communication style of Ojuelegba’s bus conductors, which he has named ‘verbal mapping’ – the act of formalising lost knowledge, unofficial language and improvised technology. “These are old buses,” he explains, “they don’t have digital signs. So you have to rely on your ear and the bus conductor calling out those stops. When you have multiple buses calling out the same routes, the conductors try to make their voices unique, pitching their voices in different ways. It becomes almost like freestyle rap.”

Following the album’s introduction, comes Wole, which is the Yoruba word for ‘enter’. It reveals the sophisticated evolution of Ogboh’s production sound. Here, he harnesses the distorted, gauzy calls of the conductors with a deeply hypnotic and dubby instrumental; the sense of entering a new space, and really sinking into it, is palpable.

“In Lagos you can hear a hundred layers of sound happening at the same time, but you can count the sounds of Berlin on your fingers”

The album then proceeds to shake off the denomination of ambient music in self-assured fashion, something Ogboh credits in part to the sound culture of his adopted home. “Sound-wise, I find Berlin boring compared to Lagos,” admits Ogboh. “In Lagos you can hear a hundred layers of sound happening at the same time, but you can count the sounds of Berlin on your fingers. But being in Berlin put me in touch with electronic music. One of the first things you do when you move here is party a lot, then after a couple years you’re done with that, but it stays with you.”

A trio of tracks at the album’s mid-point fuse these disparate worlds with particular effectiveness. Verbal Drift bumps along with little more than a sparse drum arrangement, prominent handclaps, the occasional motorbike sound, and a psychedelic symphony of voices that crowds together in urgency before dissipating again. Ayilara possesses a different type of tightly-wound tension and repurposes cat-call hissing as accents, and is executed with a UK influence. It’s followed by No Countefeit, which also functions as the thematic heart of the album: a sludgy and menacingly slow techno bruiser, with its dialogue delivering a braggadocious message of Ojuelegba pride.

“This guy is saying that he’s been in Ojuelegba for 20-something years,” explains Ogboh of the song’s featured narrator. “He started as a bus conductor, then driver, then after a while he owned his buses. He’s been blessed by Ojuelegba, there’s no other place. That’s why I chose those words – because there is no other Ojuelegba. Any other Ojuelegba is a counterfeit.”