Elizabeth Woodville was a remarkable medieval woman. King Edward IV, married her for love, not political gain. Yet, her life as queen was marred by scandal and heartbreak.

Elizabeth Woodville has enjoyed a revival of late, due to Phillipa Gregory’s novel, The White Queen, based on her life before, during, and after her queenship. Elizabeth truly was a singular medieval woman. She was known for being a classic beauty, yet there was much more to her than her face. She was a patron of education, a faithful wife, a dutiful queen and a good mother. Elizabeth paid the highest imaginable price for the love she shared with King Edward IV. By the time of her death, her star had fallen. Elizabeth’s story is a classic tale of how fortune’s wheel turns, and turns again.

1. Elizabeth Woodville: A Patroness of Queens’ College, Cambridge

In March 1465, Elizabeth Woodville became the patroness of Queens’ College, Cambridge. At this point in time, she had been wed to Edward IV for the best part of a year, but she was still two months shy of her coronation.

The college was initially founded by another English queen, Margaret of Anjou. Margaret was the wife of the ill-fated Henry VI, and like Elizabeth, she was a remarkable medieval woman. Margaret issued a charter to establish the college in 1448, and her chamberlain laid the first stone.

But it was Elizabeth who issued the college’s first statutes in 1475, reviving the college after it lost momentum when Henry lost his crown. These statutes provided for 12 fellows, some of whom were scholars, some of whom were priests. The statutes stipulated the fellows’ education, responsibilities, and wages.

Elizabeth was recognized as the true foundress of Queens’ by right of accession. The placement of the apostrophe in the word queens was changed to acknowledge Elizabeth’s revival of the college.

2. Elizabeth Woodville Lived Out Her Retirement in Bermondsey Abbey

Elizabeth Woodville retired from public life after the tumult of the Wars of the Roses, the disappearance of her sons, and her daughter’s marriage to a Tudor claimant to the throne that should have been her eldest boy’s birthright.

It was speculated that Elizabeth was sent there by her son-in-law, Henry VII, to stop her from plotting a rebellion. Some believed that she had tried to assist a Yorkist overthrow of the Tudors by supporting a pretender to the throne called Lambert Simnel. Other historians have asserted that it was Elizabeth’s wish to live a pious life in her retirement.

Either way, she spent the last five years of her life at Bermondsey Abbey, although Henry VII did provide a generous pension for her as befitted a queen dowager.

3. The Coronation of Elizabeth Woodville Hid a Secret Agenda

Elizabeth Woodville was crowned on the 26th of May, 1465, at Westminster Abbey. One chronicler described Elizabeth’s ceremonial robes as being purple in color, which would have been suitably regal. Yet, many contemporary illustrations of her coronation depict her wearing robes of blue, with her hair loose and flowing.

Scholars believe that this was a stunning piece of Yorkist propaganda. It was a well-known fact that Elizabeth was far from being a virgin, given she was a widowed mother. Therefore, in order to make her appear more appropriate as the queen of England, and the future mother of the king’s sons and heirs, she was reimagined.

In the Worshipful London Skinners’ Company’s Fraternity of Our Lady’s Assumption Book, dated ca. 1472, she is shown in blue with her loose hair in order to make her seem virginal and pure, as would have been befitting for the king’s new bride.

This royal blue is a color that artists have long associated with the Virgin Mary. Medieval women wore their hair loose as an outward sign of their virginity, whereas married women would wear their hair pinned up and covered. It would seem that Elizabeth’s coronation had a dual purpose: to put her on display for the people of London, in a sparkling show of Yorkist success, and to erase her ignominious past, as the deflowered widow of a Lancastrian.

4. Enemies of Elizabeth Woodville Thought She Had Supernatural Powers

Elizabeth’s brother-in-law, George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, was the middle of the three York brothers (Richard Duke of Gloucester being the youngest.) It was allegedly George who began to circulate rumors at court that Elizabeth Woodville was a witch.

There were two reasons these rumors carried such weight. Firstly, superstition abounded around Elizabeth’s mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg. As the story went, Jacquetta was descended from a water spirit, Melusine, who ensnared the love of a nobleman with her strange beauty. Melusine forbade her husband to see her bathe. One day, his curiosity got the better of him and he spied on her. To his shock, he discovered that she was half-woman, half-fish.

Secondly, the taint of Edward and Elizabeth’s secret marriage followed them for many years after they were wed. The nobility must have been perplexed at Edward’s marriage to the daughter of a knight, given that his kingship was new and precarious in the face of his Lancaster enemies. A political match with a foreign princess would have bolstered his stability on the throne. Yet Edward threw this opportunity away for the love of a woman who had a beautiful face and not much else.

It was convenient for George to spread rumors about his sister-in-law. George had colluded with their cousin, Warwick the Kingmaker, to have Edward deposed after his unwise marriage. According to legend, the king had the disloyal Duke of Clarence drowned in a barrel of his favorite wine for his trouble.

princes tower james northcote 1786 elizabeth woodville

The Murder of the Princes in the Tower, by James Northcote, 1786, via Historic Royal Palaces

Years later, Richard would capitalize on these rumors. He asserted that the royal marriage was null and void, due to Edward’s prior engagement to a widow called Eleanor Butler. This made Edward and Elizabeth’s children illegitimate, enabling Richard III to seize the throne in 1483.

5. Unlike Other Medieval Queens, Elizabeth Woodville Was Actually English

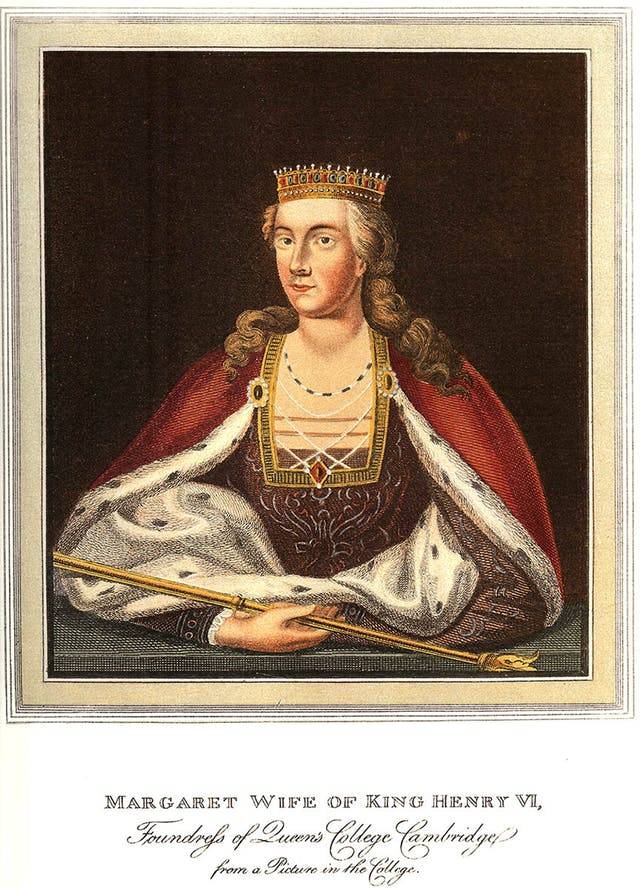

margaret of anjou elizabeth woodville queens college

Margaret, wife of King Henry VI, J.W. Cook, 1714, via Queens College Cambridge

While Elizabeth Woodville may not have been of noble birth, she was English through and through. This would no doubt have been beneficial to both her and the king, for she did not have to shed any strange ways that might make the populace wary of a foreign queen. The fact that she looked, sounded, and dressed as an English woman must have endeared her to people.

Henry II’s wife was the quarrelsome Eleanor of Aquitaine, who was French by birth. So too were many other medieval queens, including Isabelle of Angouleme — who was so cunning that she was known as “the She-Wolf of France.” Another French queen, Margaret of Anjou, who was queen consort before Elizabeth, would have been considered an unnatural medieval woman. This is because she took on the dominant role in her relationship with her weak husband, Henry VI.

Elizabeth must have been a breath of fresh air to the English because she extolled the virtues of a medieval English queen. She was a fertile wife, a good mother, pious, and during her marriage, she did not meddle in the political affairs of men.

6. She Went Through Unimaginable Heartbreak

Elizabeth Woodville lost her first husband, Sir John Grey, in the Wars of the Roses. She had to fight for the inheritance of her first two sons from him. Her father, Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers, and her brother, John, were beheaded after their defeat fighting for the Yorkists at the Battle of Edgecote Moor.

She lost her second husband, Edward IV, when he died prematurely of unknown causes at the age of 40. This left their sons exposed to the machinations of their uncle Richard, and the Tudors, who were waiting in the wings for an opportunity to strike. Elizabeth’s second son by Sir John Grey, Richard, was executed alongside another one of her brothers, Anthony, on the orders of Richard III.

Finally, and the most heartbreaking of all, her two sons by the king — the heir and heir presumptive to the English throne — were taken from her custody under the guise of protection to the Tower of London. She would never see them again.

The disappearance of the two “Princes in the Tower” was to become one of the most infamous and enduring mysteries of all time, with both Richard III and Henry VII becoming prime suspects in their disappearance and presumed murder. Elizabeth’s boys were only 13 and 9 years old.

7. She Embodied the Classic Beauty of a Medieval Woman

marriage elizabeth woodville medieval woman

The marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, from Vol 6 of the Anciennes chroniques d’Angleterre, by Jean de Wavrin, via the National Library of France

The standard of beauty for a medieval woman was consistent in both literature and art from the period — long fair hair, cat-like eyes, an oval face, a high forehead, plucked eyebrows, a small mouth, and a slender physique. Elizabeth Woodville had all of these attributes. Accounts of her physical appearance, as well as depictions of her in portraits, stained-glass windows, and illustrations, indicate she was a classic beauty. If the story of Edward falling head over heels in love with Elizabeth the moment he laid eyes on her is true, then she must have been very beautiful indeed.

8. Elizabeth Woodville May Have Died of the Plague

medieval funeral elizabeth woodville british library

An illuminated manuscript of a medieval funeral procession, via the British Library

Little was seen of Elizabeth after she retired to a life of religious contemplation, apart from her presence at the birth of her grandson, Prince Arthur. When Elizabeth Woodville died at the age of around 55 years in 1492, her son-in-law Henry VII had her buried quickly, and without the ceremony, that would have befitted a royal medieval woman. It could not go without notice that her speedy and simple funeral was not befitting a woman of her rank. This has led to some speculation that she died of the plague.

Some 19 years after her death, the Venetian ambassador Andrea Badoer wrote in a letter dated July 1511 that she had indeed died of the plague and that the king had been “disturbed.” Yet, in her final will and testament, Elizabeth instructed that she have a simple funeral, before being interred next to her beloved husband Edward.

Either way, it would seem that Elizabeth was granted her dying wish. She was laid to rest beside him in St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, where this intriguing woman rests to this day.

SOURCE : Thecollector