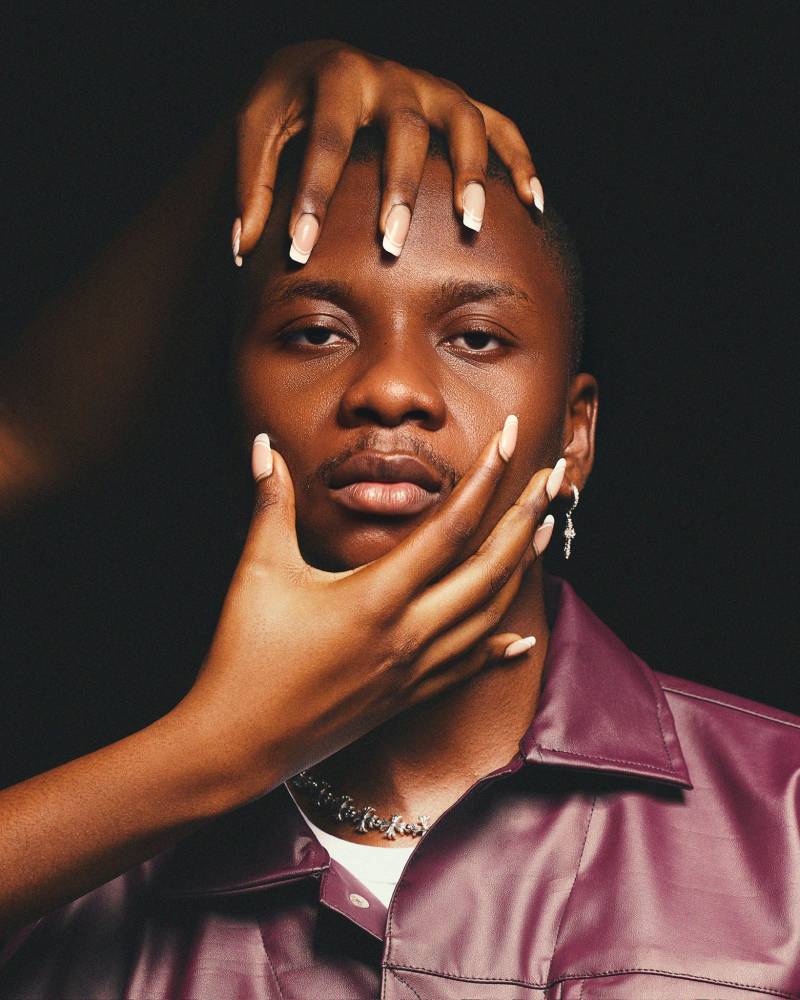

On a Saturday morning, Ayo Edebiri is discussing her first name. The restaurant required I put in my name for the breakfast order, a mundane request for most people but a potential point of distress for those of us with phonetically daunting monikers. The stakes are low if you’re a journalist but much higher if you’re a young actress and writer with one of the most electric careers of the moment — and a summer slate that’s poised to further cement her stardom. Ayo (EYE-oh) is a star of The Bear, FX’s restaurant-set dramedy that became a runaway hit last summer and returned for season two in June. She has film roles in Theater Camp, Bottoms, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem; makes a memorable appearance in the much-discussed first episode of Black Mirror‘s latest season, “Joan Is Awful”; and will join the Marvel Cinematic Universe with Thunderbolts alongside Florence Pugh, David Harbour, and Steven Yeun. Yet she still recalls (and sometimes still endures) the countless incorrect pronunciations. “I know that feeling of anticipating somebody being confused over your name well,” she says when I explain my awkward reaction to the hostess’ well-meaning request and aversion to correcting people. “But we might as well try.” Edebiri, open, warm, and quick to banter, has spoken in the past about having little in common with The Bear‘s Sydney Adamu, the earnest and occasionally vexing sous chef (and eventual chef de cuisine) to Jeremy Allen White’s culinary wunderkind Carmy, but it quickly becomes clear they share a fastidious attention to detail, a need to get things just right. “Sometimes when I do these interviews, I can tell I’m a writer because when I speak, it’s just a first draft,” she says of her tendency to correct herself or cast around for the best turn of phrase. “I’m deleting and editing in real-time.” (A member of both the Writers Guild of America and SAG-AFTRA, Edebiri spoke with THR before the actors guild called a strike on July 13.) Another similarity: Both Sydney and Ayo seem to know everyone in the local restaurant scene. Shortly after we’re seated at a corner table at All Time, a trendy café south of Griffith Park where the menu is scrawled onto butcher paper nightly, she recognizes several people. We’ve barely made a dent in our respective bowls of yogurt and chia-forward granola when she spots a table full of friends from the neighborhood. She stops to chat with a runner who also works at Little Dom’s, the ever-popular Italian joint up the street. Later, when we’re at Dinosaur Coffee, the baristas around the counter ask about her dog, Grommet, and her vacation plans; there’s a facetious request to bring back some clothes from Paris Fashion Week (“No, yeah, I’ll definitely think about it,” she deadpans). She’s made fast friends across the entertainment industry, too, finding her footing quickly despite entering a cutthroat environment without a single connection.

Edebiri, 27, grew up in what she describes in her stand-up act as the “gorgeous Caucasian haven of Boston, Massachusetts,” an only child of immigrant parents (her father is Nigerian, her mother from Barbados) with a large extended family and equally large church circle. She remembers being social in high school, being good at school, being very involved with clubs and improv. “I was definitely dealing with a lot of hormones and undiagnosed things swirling around, but I was also very focused on sorting out my adult life,” she says. “I’m a future person, always wondering what’s the next move. I’m very rarely here.” That future was New York University, where she enrolled to study education before ultimately switching to its Tisch School for the Arts (and the Dramatic Writing program) once she decided to give herself entirely over to her show business aspirations. She worked multiple jobs in addition to the coursework and her near-nightly stand-up shows, moonlighting as a nanny, a barista, and (as is The Bear canon by now) in restaurants, including Jean-George Vongerichten’s ABC Kitchen. The school introduced her to a cadre of fellow strivers in an environment she describes as similar to a conservatory: “Writing was all I could think about — I was in the deep end.” Edebiri had a plan to break into the business. She was going to give herself three to four years to get a writer's assistant job and then another four years to get staffed. Cold emails to reps led nowhere. Instead, her manager found her after reading a humor piece she had co-written for The New Yorker (“So You Want to Date a New York Museum”) and eventually came to see her act.

Edebiri’s first entertainment job was helping in the writers' room of Franchesca Ramsey’s Comedy Central pilot (which never made it to air). She then flew to Los Angeles for meetings and landed punch-up gigs on various scripts. She was still performing in as many stand-up shows as she could manage, and the right people started to take notice. “I had no framework for this kind of career,” she says, “but I think a little bit of delusion is healthy here. Because we’re doing a delusional thing. A career in the arts? It’s delusional.” By 2019, she was living in Los Angeles and writing on Sunnyside, the one-season-long NBC comedy created by Kal Penn, and she joined Rooms for Dickinson and Big Mouth soon after — all according to her plan, but much, much faster. Edebiri wrote on Big Mouth and later voiced the geeky teenager Missy after Jenny Slate stepped down during the summer of 2020 amid controversy over her voicing a mixed-race character as a white actress. On Dickinson, the Apple TV+ series reimagining Emily Dickinson’s early days, she was hired as a writer and was later cast as the supporting character of Hattie, a maid, and friend of Hailee Steinfeld’s titular poet. She always had an eye toward performing and says that she has adapted her career plan accordingly. “I’m now always checking in with myself and giving myself space for my goals to shift as my life shifts,” she says, also noting that she can be coy with the way she articulates her creative desires. “Even if I’m phrasing things in a way like, ‘I don’t know what I want,’ it’s because I know.” It was while on Dickinson that Edebiri met Christopher Storer, who directed two of Edebiri’s episodes. At the time, he was still developing the show that would become The Bear. When it came time to cast it, he quickly thought of Edebiri for Sydney.

The Bear changed everything. The series, about an award-winning chef who returns to Chicago to salvage the family restaurant after his brother’s suicide, was a sleeper hit last year and earned nearly universal critical acclaim. It launched several (overlapping) fandoms — the earliest, and often the loudest, revolves around the internet’s obsession with and babygirlification of White as Carmy, the tortured and tattooed bad boy with a heart of gold (sort of), but a close second was Edebiri’s performance as the hyper-driven Sydney. Earlier this year, White won the Golden Globe, and Edebiri took home a Spirit Award for best-supporting performance in a new scripted series. In July, they were both nominated for Emmys (in addition to the show’s outstanding comedy series nod). Season two follows the crew of the cult sandwich shop The Beef as they struggle through attempts to flip the restaurant into a fine-dining establishment, a process that opens up the storylines of the whole ensemble and complicates the emotionally charged relationship between Carmy and Sydney. Their dynamic as professional partners is stress-tested by the horrors of opening a new restaurant (red tape, budget woes, mold, oversalting a test dish) and by Carmy’s budding romance with an old friend (played by Molly Gordon, co-director and co-star of Theater Camp). After all 10 episodes dropped on June 22, the premiere became the most-watched FX show on Hulu (the networks won’t release streaming numbers but noted that the audience was 70 percent higher than the first season during the same time frame).

Edebiri is not involved in writing The Bear, though Storer has shared his plan for a third season with her — she won’t tell me what it involves, only that it “makes sense” to her. “I guess I want Syd to keep pushing,” she says. She’s also been made aware of the (seemingly) sizable group of Carmy-Sydney shippers that have appeared, rising from the Twitter mist to declare their allegiances to an imaginary romance. These fan theories are something of a pain point for Edebiri, who says she is grateful that people are so engaged with the show, but that it’s “frustrating.” She adds: “It’s really not our thought process when we’re making the show, and I understand it can be part of a show’s culture — but I don’t think they’re going to get what they want.” Gordon told THR that while she also doesn’t subscribe to the shipper theories, she believes it’s a testament to the work of Storer, White, and Edebiri that they’re able to create something so passionate. “I think it’s incredibly cool to have this dynamic onscreen that isn’t romantic, but that feels charged and sexy,” she said. Narratively speaking, Edebiri isn’t actually sure that Carmy should be in a relationship with anyone (“It’s TV, do you want to see Walter White go to therapy and then reunite with his family?” she asks with a laugh), but admits that she can’t resist falling — platonically! — for the character’s complicated charms. “I love this little fucked up guy in the kitchen,” she says before quickly self-editing. “Or wait, this messed-up guy.” (The more she reads her own interviews, the more she sees her own explicit language: “I think I do it when I’m telling a joke like I’m putting a swear in there to let you know I’m saying a joke — it’s something for me to reflect on.”)

At this point, I remember — and bring up — a tweet I saw recently, that drew a line between the many years that Succession fans spent caring (deeply) about the show’s (deeply) damaged men and the way they were able to quickly jump to the stage of “babygirlifying” the men of The Bear. She looks aghast, the parasocial implications a step too far even for someone from her inherently online cohort. “That is so Internet,” she manages, her expression a flash of the face-acting that has become a hallmark of her Emmy-nominated performance. As The Bear’s main characters went on their own journeys this season, it created moments of quiet — a creative pivot that felt rewarding to the viewer but often lonely for its actors, who grew to love the fast-paced, raucous, highly choreographed scenes in The Beef’s back-of-house. Ebon Moss-Bachrach, who plays hotheaded “cousin” Richie, previously told THR that he “mourned” the loss of those chaotic days, and Edebiri felt a similar melancholy while filming episode three (“Sundae”), which follows Sydney as she travels across Chicago for culinary inspiration. “It was just two weeks of shooting me eating food and being in the cold, and I was by myself and missing everybody,” she says. “That’s the hardest type of acting for me, where it’s like, you’re a person, by herself, being vulnerable. There are 40 teamsters around and I’m just by myself in front of everybody.” (But she did love that she got to contribute something from her own closet to Sydney’s wardrobe: that quirky little detachable puffer hood. “It’s sick,” she says with glee. “Next winter everyone is going to be buying this shit, but it’s fine. I’m happy I did it.”) Storer brought back some of season one’s notorious chaos for “Fishes,” the flashback Christmas episode that offered a window into Carmy’s deep-seated trauma. The stand-alone brought in such heavyweight guest stars as Jamie Lee Curtis (as Carmy’s mother, Donna Berzatto), Jon Bernthal, Sarah Paulson, Bob Odenkirk, John Mulaney, and Storer’s longtime partner, Gillian Jacobs. Edebiri does not appear in “Fishes” — she shadowed Storer on set as he directed the episode and was given a co-executive producer credit.

She says Storer noticed her aspirations before she saw them in herself: “When I met Chris, he was like, ‘You’re going to be a director’ — I just said, ‘Cool, you’re directing my life, and I love it.’ ” She says she is indeed interested in more producing and directing work and was greatly inspired by Storer’s collaborative style. Watching an ego-less showrunner at work, she says, taught her that “you can be a director without being omnipotent; you’re not an almighty power floating in the sky with a little monocle and a megaphone, or whatever.” Two of the other releases that make up this Summer of Ayo — Theater Camp (out now) and Bottoms (Aug. 25) — are helmed by close friends, part of a growing web of close collaborators. Edebiri met Bottoms co-writers Rachel Sennott and Emma Seligman while at NYU. Seligman later directed Sennott and Gordon in her feature debut, Shiva Baby; during filming, Sennott organized a “girls hang” to introduce Gordon and Edebiri. “She lost her credit card within the first hour of being there, so I felt like we were going to be friends,” Gordon recalls. In Theater Camp, a mockumentary about a summer arts camp under threat of financial insolvency, Edebiri appears alongside Ben Platt and a bevy of comedy’s rising stars like Patti Harrison, Jimmy Tatro, Noah Galvin, and Owen Thiele. Gordon wrote the part of an instructor who lied on her résumé to get the job specifically for Edebiri, relishing the idea of allowing what she saw as Edebiri’s “unbelievably wacky” side to flourish.

The character that Edebiri brought to the screen vacillates between deadpan delivery and energetic outbursts, which feels reminiscent of her early stand-up work, and occasionally borders on the nonsensical, much like her social media presence. (See her Twitter bio, which identifies her — incorrectly and without explanation — as “Showrunner of The Kominsky Method, now streaming on Netflix, Vudu, and the ITV app.”) The Bear’s first season dropped the day that Edebiri started filming Theater Camp with Gordon in upstate New York, offering a striking view into the actress’ range. “She can be messing around and goofing off, and then the second the camera rolls, she’s delivering the most dropped-in performance you’ve ever seen,” says Gordon. Edebiri’s part in Bottoms was also written just for her. Seligman and Sennott had been working on the film — about queer teenagers who start a fight club at their high school to get closer to their crushes — since 2017, and once they decided to make the raunchy romp a two-hander, Seligman suggested their mutual friend play opposite Sennott. Seligman met Edebiri at a party and remembers an inherent sweetness that she now sees reflected in the way she performs. “She was just so awkward and funny and nerdy,” Seligman says, “and had such a good handle on slapstick physical humor that you never really see in the alt-comedy scene.” She references an early bit from Edebiri’s stand-up where she does an impression of an emcee/hype man trying to work for the crowd despite feeling debilitatingly sad; there’s also a moment from a landmark Comedy Central set wherein the comedian makes fun of her own brand-new, blindingly white Vans, punctuating the joke with a Molly Shannon-esque high kick. As Edebiri recalls, she had to audition for the role that had been custom written for her. “I’m still slightly salty about it,” she says. “I don’t know who made me audition, but I passed.” Seligman recalls it as more of a chemistry read — a “box to check” for the studio (Orion) to give its blessing on the onscreen matchup between Edebiri and Sennott. The actress already had been cast in The Bear, but the show hadn’t been given the season order. “Her résumé was good and it was already obvious that her career had so much promise,” says Seligman, “but it was cool to feel validated that we all saw something.” On the day of our interview, Edebiri is flying to Paris to attend the debut Thom Browne couture show, which will also be her first-ever fashion show. The brand has a knack for tapping into the cultural moment — Browne’s Fall/Winter 2022 campaign featured Euphoria‘s Angus Cloud and Chase Sui Wonders of Bodies Bodies Bodies, and he has dressed Cloud’s co-star Maude Apatow as well as Yahya Abdul-Mateen II. “I wouldn’t say I’m totally comfortable in that world, but I’m learning it,” she says. “Right now, I’m like, ‘How should I be at a show?’ ” Though she’s often in the ultra-casual wardrobe of a Los Angeles screenwriter (today’s ensemble includes a denim jacket and sweatpants), she loves clothes, and her growing fame gives her greater entrée into the space. Recent press appearances have seen her in everything from heritage luxury brands like Valentino to ready-to-wear from Rosie Assoulin and Ernest W. Baker.

She’s becoming something of a Browne devotee in her own right — she wore one of his signature suits when she accompanied him to the CFDA Awards, and he created the custom chef jacket that Carmy gifts Sydney in The Bear‘s season two finale. Here at All Time, the morning has gotten a little away from us. We met at 8 o’clock on the dot so she can catch her flight tonight. After the Thom Browne show in Paris, she’ll shoot THR‘s cover, then pop over to London, Copenhagen, Minorca, and Lisbon to see various friends. The trip came out of a realization that, during interviews, she was constantly asked questions like “When do you sleep?” or “When are you going to take a break?” without a good answer. She seems a little bit anxious. She hasn’t packed yet, and now the dog sitter is en route to her house for the handoff, and we’re still picking chia seeds out of our teeth. We wrap up quickly — she’s barely touched her oat milk cappuccino in its handmade speckled-beige ceramic mug — and she drives us back to her house, Grommet balancing daintily on my knees. After Grommet is safely ensconced in the dog sitter’s car, we walk for more cappuccinos (iced this time), and the conversation turns to relationships. She’s on good terms with her ex, who is in the process of moving from New York to Los Angeles and will soon be another source of pet care (apparently great terms is more like it) and is intrigued by my own (relative) apathy toward marriage. “You could do a small party, which is my dream, even though it’s crazy because my family is so big,” she says. “If I ever had a wedding …by the way, literally, who am I dating?”

After we’re situated on the back patio of Dinosaur Coffee, a man approaches, bursting to offer his congratulations on Edebiri’s recent success. His companion quickly chides him for interrupting, putting her in the uncomfortable position of having to make this stranger feel better for having entered her space. She has described a singular drive to enter the entertainment business as a writer, but given her seemingly fated pivot to on-camera work, I’m curious whether she ever stopped to consider if it would make her truly famous. “No, I’d be insane,” she says. “Some people are literally supermodels, so it makes sense that their life would change.” She didn’t imagine herself in the spotlight because that would betray the self-deprecation inherent in her comedy work, and now she’s having to make sense of phenomena like fans screenshotting her online film reviews from Letterbox’d (posting on the site is “supposed to be fun,” she says, “and that makes it not fun”) or being asked to do things like this interview. I ask whether she enjoys (or tolerates) watching herself onscreen, and she explains that, for now, she’s able to “zoom out” and not get in her own head but that it will get harder if she’s ever the lead of a project. Wasn’t she essentially the lead of The Bear’s second season, I wonder? She begins talking about how the show opened up for all the characters and how much she loved Moss-Bachrach’s work, particularly in episode seven. “This deflecting,” she adds with a grin. “Do you like it?” And then it’s nearly time to go — there are books to pack (David Grann’s new nonfiction) and shoes to ponder over (“What about a sneaker and a ballet flat?” she asks. “Those are two good shoes.”) She entertains a final question about Thunderbolts, the upcoming Marvel antihero film that, at least until the SAG strike, was supposed to start filming this summer and hit theaters next July, employing a deft evasiveness one can only assume is taught in some sort of pre-Marvel boot camp.

What can you tell me about Thunderbolts? I ask. “I know that I’m in it, and I’m excited to be in it,” she says. Do you have to keep your schedule clear in the meantime? “I don’t know.” You don’t know … “I don’t know. I know that I’ve been cast.” So you signed something … “I don’t know.” I pivot, remarking on how stressful that sounds — that most people would struggle with that lack of control. “It actually isn’t,” she says. “You’ve got to embrace the unknown. That’s literally half of my therapy — it’s just my therapist being like, ‘Isn’t not knowing exciting?’ And I’m like, it actually is kind of beautiful. It’s kind of sick. I’m at a place where my life has opened up in all these different ways, and I’m trying to be there for it, to be an active participant in my whole life and be OK with making mistakes,” she says, then obliquely references her moment of ubiquity. “The biggest thing I’ve learned is that you have to rely on people. You can’t do this on your own. Sometimes I just ask friends to get a drink so I can complain, or to get a drink so they can tell me about their life and I can remember there are bigger things than this.” It’s a valid point, but this, it must be said, feels pretty freaking big.

“gorgeous Caucasian haven of Boston, Massachusetts,” an only child of immigrant parents (her father is Nigerian, her mother from Barbados) with a large extended family and equally large church circle. She remembers being social in high school, being good at school, being very involved with clubs and improv. “I was definitely dealing with a lot of hormones and undiagnosed things swirling around, but I was also very focused on sorting out my adult life,” she says. “I’m a future person, always wondering what’s the next move. I’m very rarely here.” “Writing was all I could think about — I was in the deep end.” “I had no framework for this kind of career,” she says, “but I think a little bit of delusion is healthy here. Because we’re doing a delusional thing. A career in the arts? It’s delusional.”

“I’m now always checking in with myself and giving myself space for my goals to shift as my life shifts,” she says, also noting that she can be coy with the way she articulates her creative desires. “Even if I’m phrasing things in a way like, ‘I don’t know what I want,’ it’s because I know.”

“It was just two weeks of shooting me eating food and being in the cold, and I was by myself and missing everybody,” she says. “That’s the hardest type of acting for me, where it’s like, you’re a person, by herself, being vulnerable. There are 40 teamsters around and I’m just by myself in front of everybody.” (But she did love that she got to contribute something from her own closet to Sydney’s wardrobe: that quirky little detachable puffer hood. “It’s sick,” she says with glee. “Next winter everyone is going to be buying this shit, but it’s fine. I’m happy I did it.”)

What can you tell me about Thunderbolts? I ask. “I know that I’m in it, and I’m excited to be in it,” she says. Do you have to keep your schedule clear in the meantime? “I don’t know.” You don’t know … “I don’t know. I know that I’ve been cast.” So you signed something … “I don’t know.” I pivot, remarking on how stressful that sounds — that most people would struggle with that lack of control. “It actually isn’t,” she says. “You’ve got to embrace the unknown. That’s literally half of my therapy — it’s just my therapist being like, ‘Isn’t not knowing exciting?’ And I’m like, it actually is kind of beautiful. It’s kind of sick. I’m at a place where my life has opened up in all these different ways, and I’m trying to be there for it, to be an active participant in my whole life and be OK with making mistakes,” she says, then obliquely references her moment of ubiquity. “The biggest thing I’ve learned is that you have to rely on people. You can’t do this on your own. Sometimes I just ask friends to get a drink so I can complain, or to get a drink so they can tell me about their life and I can remember there are bigger things than this.” It’s a valid point, but this, it must be said, feels pretty freaking big.

HollyWoodReporter