Delivering an inaugural lecture as the Mercers’ School Memorial Professor of Business at Gresham College, Daniel Susskind introduced the term “automation anxiety” to capture the escalating public fear surrounding the implications of rapid technological progress. Susskind began by contextualizing this moment, noting that the release of ChatGPT in November 2023 was a pivotal event, quickly becoming the fastest-growing application in history began by contextualizing this moment, noting that the release of ChatGPT in November 2023 was a pivotal event, quickly becoming the fastest-growing application in history. This progress gives credence to the ambitious claims of leaders at major AI companies, such as Demis Hassabis at DeepMind, Dario Emord at Anthropic, and Sam Altman at OpenAI, who predict that within a decade they will build systems capable of outperforming human beings at all economically useful tasks.

While such claims might sound like science fiction, Susskind argued that they must be taken seriously for three reasons. First, the sheer scale of financial resource currently directed toward AI is extraordinary, estimated by computer scientists like Stuart Russell to be ten times the investment of the Manhattan Project, paralleled perhaps only by the Apollo moon landing. Second, higher education is undergoing reorganization, with the share of bachelor's degrees in computer science in the U.S. approaching the total share of all humanities degrees. Finally, progress is advancing so rapidly that it is reportedly outstripping our capacity to generate new benchmarks to monitor it.

Related article - Uphorial Radio

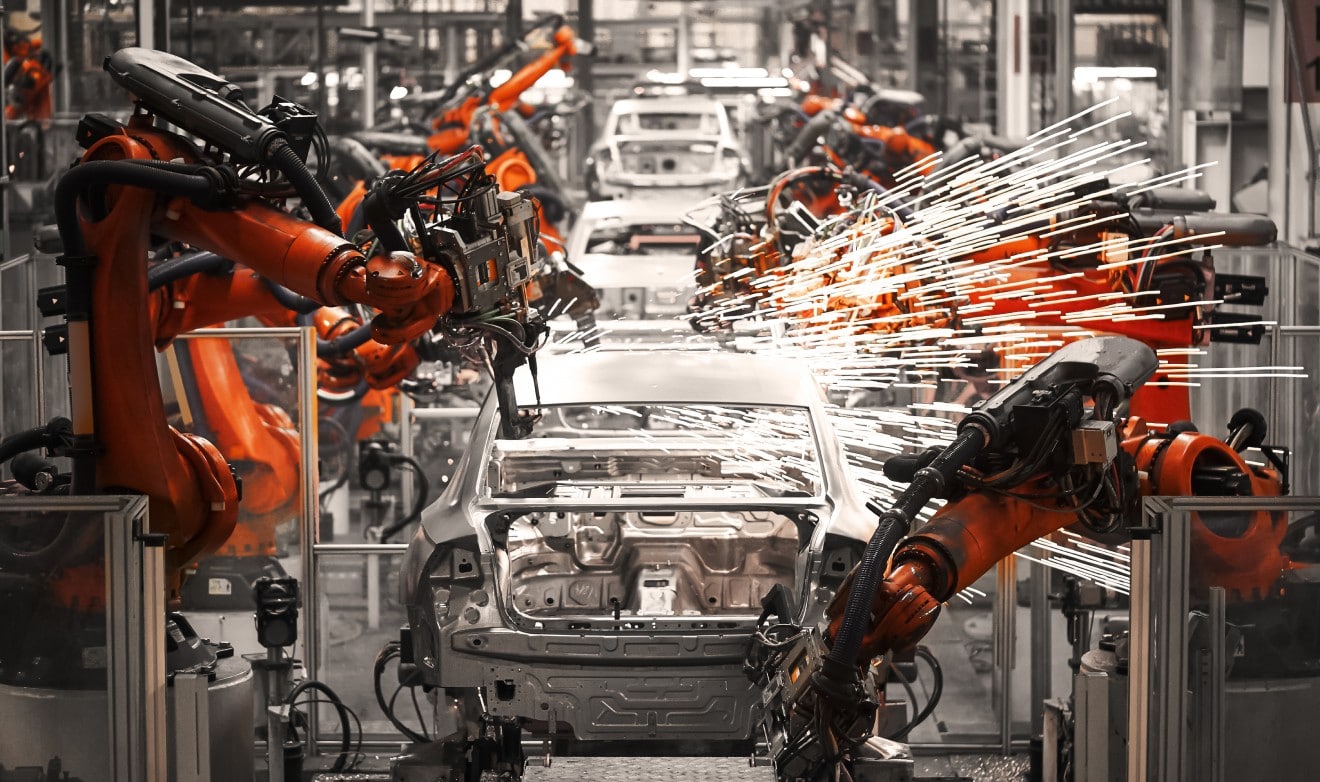

This technological surge has resurrected an old fear: that machines will eliminate jobs, leading to widespread "technological unemployment". This anxiety, which has flared up periodically since modern economic growth began two and a half centuries ago, is what Susskind calls automation anxiety. Historically, this fear has been most famously embodied by the Luddites during the Industrial Revolution. Named after the apocryphal weaver Ned Lud, these anxious people smashed new technologies like spinning jennies and roller spinners, prompting the British Parliament to make machine destruction a crime punishable by death in 1812. Today, this anxiety persists, manifested in acts like setting fire to driverless cars or attacking autonomous delivery robots.

However, the primary fear driving historical automation anxiety—that new technologies would destroy jobs and leave large pools of permanently unemployed people—has consistently been proven wrong. Unemployment has generally remained stable, even hitting record lows in recent years in places like the U.S. Consequently, the term "Luddite" is often used today as a disparaging label. Susskind argued that dismissing automation anxiety is a mistake because, while the Luddites were wrong about the number of jobs, they were profoundly right about the detrimental impact technology had on the nature of work. The core argument is that the Industrial Revolution harmed the nature of jobs in four critical ways—pay, quality, status, and power—a pattern that appears to be unfolding again with AI.

First, regarding pay, the extraordinary technological progress of the Industrial Revolution did not immediately translate into higher wages. Real wages in England barely rose until the turn of the 19th century, a phenomenon the economic historian Robert Allen dubbed "Engels' pause" (1770–1840). During this time, GDP per worker rose substantially, but the gains went primarily to industrialists like Richard Arkwright, not workers. Similarly, despite remarkable technological progress over the last two decades, average real wages in the UK have stagnated for 16 or 17 years, the longest such run since the Napoleonic Wars.

Second, the quality of work collapsed. Contemporaries like William Blake referred to the new factories as "dark satanic mills," and Karl Marx famously critiqued capitalism, arguing that new technologies mutilated the laborer into an "appendage of a machine," turning work into "hated toil". Today, similar concerns arise, particularly regarding the insecurity and unpredictability of the platform economy and the often-degrading tasks, such as content moderation for social media, that new technologies create.

Third, the status of work is being challenged. The 20th century was defined by skill-biased technological progress, driving an exponential increase in computational power that led to a rising "skill premium" for college-educated workers. However, the Industrial Revolution saw a falling skill premium. New mechanical technologies were "deskilling," making it easier for people with less specialized training to take the place of skilled workers like Ned Lud. Today, a similar trend may be emerging, with predictions that AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs, suggesting that the status of skilled labor may be threatened.

Finally, technology facilitated significant power imbalances. Industrialists who accumulated wealth during Engels’ pause—such as Richard Arkwright, Sir Robert Peel the Elder, and Josiah Wedgwood—also accrued immense economic and political influence. Similarly, today, large technology companies like Meta, Amazon, and Google hold extraordinary economic power. Their technologies shape the "social scaffolding" of modern life, constraining liberty and determining questions of social justice, such as loan eligibility or parole decisions.

Susskind concluded that narrowly focusing on the number of jobs is unhelpful. If we are to understand the true impact of artificial intelligence, we must heed the lesson of the past: automation anxiety must be taken seriously not because this time is different regarding job destruction, but because new technologies, once again, appear to be undermining the pay, quality, status, and power associated with human work.