Who gets to decide what goes on the walls of our museums? That quiet but revolutionary question has nagged at Sonia Boyce ever since she first visited London galleries in her teens. Her 40-year inquiry into it, as an artist and academic, culminated in outraged tabloid headlines in 2018 when, as part of an exhibition of her work at Manchester Art Gallery, she temporarily removed a painting from the gallery’s “permanent” collection – JW Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs – and replaced it with an empty space in which visitors could leave Post-it notes recording their thoughts about the depiction of women in the gallery.

For some male commentators, this was a blood-pressure elevating act of cancel-culture vandalism on a level with toppling statues of slave traders into the drink. Boyce had a point, though. While only 8.5% of the paintings then chosen to be on display in Manchester were by female artists, there were 44 paintings by men, including Waterhouse’s Victorian Greek fantasy of a bathing pool full of virginal, flame-haired girls, depicting women naked or semi-clothed. Why?

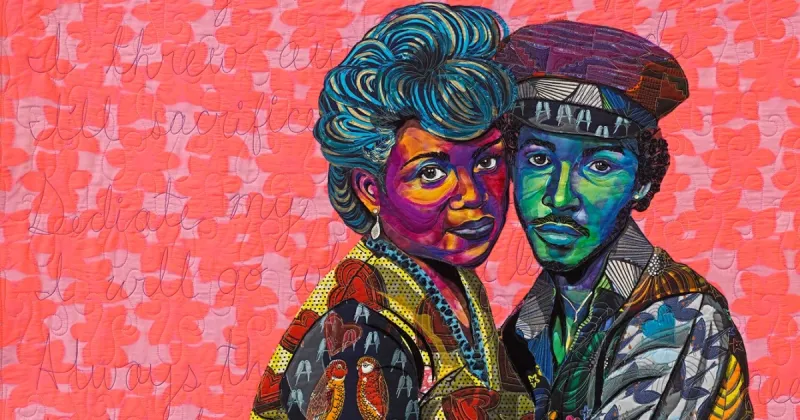

Boyce will have another playful crack at that history of curation in her forthcoming show as Britain’s representative at this year’s Venice Biennale. She is the first black woman to have been chosen by the British Council for the national pavilion, at the 59th Venice event. Turning 60 this year, Boyce is used to ground-breaking. She was also the first black British female artist to have a painting purchased by the Tate, in 1987, and the first to be elected to the Royal Academy, in 2016. Her biennale show – the full details of which are under wraps, to be announced later this week – will be a development of Devotional, her long-term project dedicated to the often hidden or forgotten history of black British female musicians and singers.

When I go to see Boyce at her Brixton studio, she is in between visits to Venice to install the exhibition – and if that were not anxiety enough, also moving house the following day. If she is stressed, she doesn’t show it; compact and spirited, she talks with the vocational ease of someone who has been turning over the ideas behind her work all of her life. Her studio is a single small room in a block just down the high street from Electric Avenue. Stacked against one wall are some of her latest artist’s materials: boxes and crates of vinyl singles and LPs.

The temporary nature of those crates is appropriate. Boyce thinks of herself as “an artist with a suitcase”, on the road all the time. The Devotional music project began in 1999 when she was invited to work with a charity, the Liverpool Black Sisters, in Toxteth. “The plan was to do a six-month project and create an artwork,” she recalls. It being Liverpool, she thought: music. “In the very first session we all sat around in a circle and I said: ‘Can someone name me a black British female singer they love?’ There was lots of umming and ahhing, and then silence.” It took the group about 10 minutes before anyone could name anybody – Shirley Bassey – at which point, they all got up and sang Big Spender. And then they sat down again and thought some more.

“The group were really embarrassed about their silence,” Boyce says. “They went home and asked friends and family for suggestions and by the end of that six-month period, we had gathered 46 names.” The list ran from Bassey to Joan Armatrading to Poly Styrene (of X-Ray Spex) to Sade and Pepsi from Pepsi and Shirlie and Cleo Laine. With the help of the group, Boyce made an exhibition involving sound and collages and placards and her trademark wallpaper devoted to the performers and their stories. She thought that was the end of it, but it was only the start. People kept sending her more records, and the Devotional list for Venice now runs to 350 names, dating back to the mid-19th century.

For Boyce, some of the interest is in how the names and their music provide a sort of alternative history, often buried, of the crisscrossing currents of female culture between the Caribbean and Britain, and America and Africa over the past century and more. It provoked memories of how, growing up in east London, she would go to record shops to get under-the-counter vinyl imports with lyrical news from elsewhere, torch songs and pop songs and fresh rhythms and styles, “and then, how when you walked down the street or went in any shop, some of that became the background to our lives”.

She uses her handmade wallpaper as a kind of visual motif for that memory. “As a child – like many, I’m sure – I often imagined that wallpaper had a life of its own, that it was like entering a folk-like narrative world. I still get that sensation.”

The background soundtrack of her childhood came partly from her parents, who were part of the Windrush generation from Barbados. Her dad came over in the early 50s, and was working as a projectionist in a cinema in Camden Town when he met Boyce’s mother, who had arrived in London a few years later to work in the NHS as a nurse. To help make ends meet she also worked part-time as a seamstress in one of the clothing factories in Whitechapel; Brick Lane was Boyce’s playground as a child.

At home, Boyce has suggested, the wallpaper itself was a dizzying reminder of Caribbean pattern and colour, and the record collection no less disorienting. The cowboy crooner Jim Reeves was a family favourite. But then also lots of reggae, ska, calypso. To this she added acts from The Old Grey Whistle Test and John Peel.

By the early 1980s musicians – in Rock Against Racism and later Red Wedge – appeared to provide a model for addressing racial and sexual politics in art. There were plenty of women involved in that vanguard but, Boyce observes, 20 years later when the women of Liverpool tried to recall them, it was as if they had been written out of the story.

For Venice, she has worked at Abbey Road studios and with the sound artist Ain Bailey to explore some of that forgetting. “I wanted to activate the Devotional collection somewhat,” she says. One of the artists they have resurrected in film is Adelaide Hall, who brought the Harlem renaissance to London in the 1930s, setting up a nightclub in Mayfair. Hall was among the first women to be recorded singing jazz scat with Duke Ellington. Her fame, and its erasure, is mirrored in the story of the pianist Winifred Atwell, who brought honky tonk piano from Trinidad in the 1940s, or the great soul singer PP Arnold, employed as a backing voice by every white rock’n’roll band to provide the authentic sound of the 60s.

She got a place at Stourbridge College of Art in the West Midlands. One day she was in the library and saw a little poster for a show called Black Art at Wolverhampton Art gallery, organised by artist Keith Piper. “It completely stopped me in my tracks,” Boyce remembers now. “I was born in London, grew up in London, and went to art school from about the age of 15, but I was totally unaware until that show that there were artists of African or Asian descent working in the UK at all. I went to a Wolverhampton conference for black artists in 1982, which was the year after the Wolverhampton show. And people came from all over the UK, maybe 200 young black artists and students. It was funny, we were all in art colleges up and down the country, but feeling like we were the only one…” From that conference the groundbreaking BLK Art Group was formed.

Among the women Boyce met at that conference was Lubaina Himid, who went on to win the Turner prize in 2017 and who was a few years older than her. Himid remembers how “Sonia was already making beautifully drawn autobiographical observations, thoughtful meditations on what it was to be young female and black… She was [also] very sure of where she wanted to exhibit; showing work in places that were open to the people who meant the most to her.”

Himid insisted that Boyce send some slides of her paintings to see if they would work in a show Himid was curating at the Africa Centre in London. “After the conference I was filled with lots of energy,” Boyce recalls. She had been threatened with expulsion from college at Stourbridge because she refused to go along with the pervasive insistence on making abstract art. Her work was overtly political, full of collages depicting black women in the media, partly inspired by the music she was listening to. “I went back to the studio at college, and I remember thinking: I’m just going to go for it.” She sent Himid some images and within a few months her work was in the exhibition. That had never been part of the plan. “Before I’d gone to Stourbridge,” she says, “I’d worked part time at British Home Stores. And I just kind of thought that afterwards maybe they would take me back. Or maybe I could upgrade and get a job at John Lewis…”