Ibrahim Mahama has made some curious purchases over the past three years: a grain silo, and several aeroplanes meant for the scrapyard. In 2020, the Ghanaian artist acquired the silo, which had lain unused since the 1960s, in the town of Tamale in the country’s north. Mahama renovated the decrepit building, and opened the space as Nkrumah Volini, a cultural institution featuring exhibitions and programming for locals and younger generations that he hopes will inspire.

It’s this same drive for fostering young minds that motivated the artist to open the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA) and Red Clay Studio in Tamale, the latter of which also serves as the artist’s studio space.

The artist offers to give Tatler a mini tour of Red Clay Studio over video chat. A far cry from the stereotype of an artist’s studio—the stereotypical high-ceilinged, paint-filled room where the temperamental artist works in tortured solitude—his is more of a complex, and it’s almost always packed with visitors. As he takes us around, hordes of uniformed children are seen spilling out of school buses; the artist says they are expecting at least 2,000 visitors that week alone.

In addition to children, members of the local community frequent his spaces; Mahama hopes to get people of all backgrounds to engage with and think about art and local history in unconventional ways. “I’m building an institution within an environment which has not had this level of justice in terms of thinking about art or contemporary art in its history.”

The vast complex houses Mahama’s workspace as well as exhibition areas, archives, libraries, film screening rooms, and a large courtyard-like structure called the Parliament of Ghosts. Amongst the many intriguing sights glimpsed during the virtual tour are Mahama’s second unusual purchase: six Soviet-era aeroplanes. Far from airworthy and destined to be torn apart for scrap metal, the defunct aircraft planes were instead transformed into classrooms where schoolchildren now attend drone-operating workshops, as well as drawing and coding classes. Repurposing materials with little or no obvious remaining use is an integral part of Mahama’s intrinsically sustainable practice. “I’m interested in the fact that these objects could perform different functions and allow for new ideas to sprout,” he says.

Mahama wants to implement institutional change elsewhere in the industry, too, including in art education. He considers himself fortunate to have had professors who believed in educational reform, which allowed for new ways of thinking, despite teaching at a state-run institution. The antiquated British curriculum—which focused more on generic landscape painting than the philosophy and critical theory behind so much contemporary art—was serving no one, in his opinion. “For a long time, artists always made work as if there was nothing wrong with the world,” says Mahama. “There was no room for imagination; you just painted what you saw.” His teachers introduced new courses such as philosophy into the curriculum and, rather than the traditional approach of separating artistic mediums—drawing, sculpture, painting, etc— began combining them so students could start thinking about their practices critically and holistically.

Mahama uses a variety of scrap materials ranging from textiles to old sewing machines; but it’s jute sacks that have become most synonymous with his work. Made in Southeast Asia and collected in Ghana, the sacks were used to transport cocoa, the production and import of which the country became known for during its colonial occupation.

The sacks featured in the artist’s Out of Bounds installation, which was made for the 2015 Venice Biennale and which first caught the eye of the international art world and garnered him acclaim. The artist had wrapped two prominent walls of the Arsenale with the sacks. It was in Venice that Susan May, White Cube’s Global Artistic Director, met the artist; shortly afterwards, the mega gallery started representing him.

Half of a Yellow Sun is Mahama’s first solo exhibition at White Cube Hong Kong. The title is taken from renowned author and feminist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s book of the same name, which explores the dynamics and fragility of a newly independent Nigeria on the brink of civil war.

The exhibition features works the artist has made since 2013, but has never shown before. They are reflective of a time when he was more concerned with the visual than the political impact that his large-scale installations have become associated with, revealing a lesser-known aesthetic aspect of the artist’s work. “I never showed these works because they were very traditional and very colourful,” says the artist. “They were simply too pretty.”

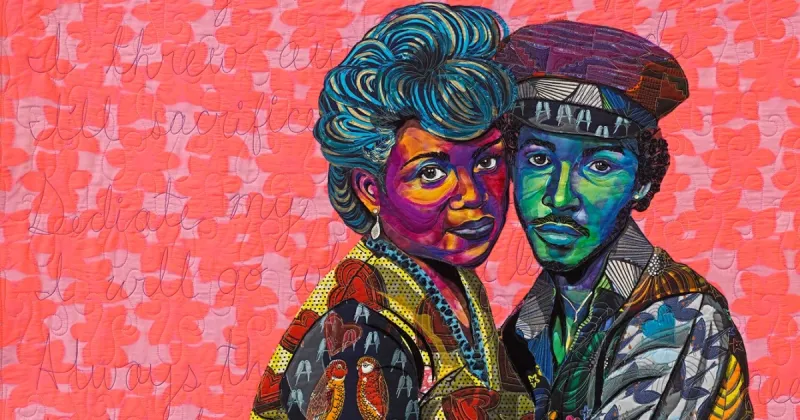

The works strike a chord both visually and culturally, and reference the global connectivity experienced in the post-colonial world. Developed around the same time as his jute sack series, the works speak to Mahama’s core preoccupation with the circulation of goods, capital, and labour, reflected in the textiles he uses. Full of vivid hues and attractive patterning, and combined into a collage-like form, the panels which constitute the works are wrapped in textiles Mahama collected and bartered for from local tradespeople (mostly women) over a period of several years.

Known as “Dutch wax” cloth, these fabrics were manufactured at a low price point, and were to be sold to the Dutch East Indian colony markets, as they replicated Indonesian batik design. Rejected by Southeast Asian markets, the Dutch sought alternate outlets to offload their product, such as West African port cities—in particular, the Ghanaian capital, Accra. The batik was modified with regionally relevant designs, and became symbolic of pan-African culture. Among other notable prints, a pattern depicting a crescent-shaped cluster of trees known as Kofi Annan’s Brains” was developed based on a brain scan of the Ghanaian former United Nations General Secretary after he made his final address in New York. Fabric with this specific print is incorporated into many of Mahama’s pieces, such as the bottom right corner of Question, Jam, Answer (2022).

All of the works on view are named after songs by Fela Kuti, the legendary Nigerian musician who was incredibly vocal in his criticism of colonialism and of the Nigerian government since the country gained independence. In invoking Kuti and Adichie’s names, Mahama highlights how artists can have a significant impact when their art speaks to a greater cause. “I like the way their work brings in a certain responsibility which speaks to how to different generations can take control of their own destiny,” he says.

This sense of responsibility infuses Mahama’s practice, manifesting itself in the form of local community engagement and shaping future generations. It is one shared by many African and African diaspora creatives who have experienced success and now give back by cultivating cultural landscapes in countries which lack infrastructural framework. Celebrated Nigerian British artist Yinka Shonibare recently opened the Guest Artist Space (G.A.S) Foundation in Nigeria; Kehinde Wiley set up Black Rock Residency in Senegal; British Kenyan painter Michael Armitage set up the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute; and Mahama’s fellow Ghanaian, renowned architect David Adjaye, co-founded The Africa Futures Institute.

“I come from a community where people do things for you without expecting anything in return,” Mahama says. From the beginning of his career, he interacted with members of the local community to produce his art through buying old materials at local markets. The relationships continued to develop when he invited them to collaborate on the large-scale installations the materials were used in. In particular ones involving jute sacks, which were sown together by many local community members.

Eventually their participation factored into Mahama opening his institutions. “I was trying to make work that would involve them in the beginning in terms of the processes,” he says. “Eventually the final product would end up being sold and the proceeds would build institutions that both they and their children could be a part of.”

Mahama’s many siblings have found success in more conventional professions as lawyers, doctors and engineers, but his father, who believed Mahama showed artistic promise as a child, thought “it would be interesting to see what would happen” if he studied art. “I’m the lab rat; I was the experiment,” the artist jokes. “It’s an inside joke between me and my father that I’m the failure of the family.” The irony, of course, is that Mahama has been immensely successful, both critically and financially; having found fans as a young artist, the works for the Hong Kong show (which are much smaller than his large-scale installations) sell for €85,000-€100,000. Most of the proceeds fund Mahama’s existing institutions in Tamale.

Mahama wants to go national, and eventually global, with his mission. He planted the first seed with his grain silo and now with the three art spaces serving as blueprints for his future plans, he is currently in negotiations for ten buildings across Ghana. In creating art spaces specific to different environments for people from multiple backgrounds, the artist is trying “to build enough pedagogical spaces so we can rearrange our way of thinking about arts and the role it plays within the generations which are yet to come” he says, “I’m banking on the future.”