Chief Curator Amy Ing recently welcomed Vogue into the legendary Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue, showcasing a Gilded Age mansion where every object serves as a window into the identities and desires of the past. Within the dining room, Ing highlights British portraits like Gainsborough’s the Honorable Francis Duncan, whose "exuberant" blue satin dress and towering "poof" hairstyle functioned as a flamboyant costume that transcended her own century. This intersection of history and high fashion continues in the west vestibule with Boucher’s Four Seasons, which prioritized the luxury of privilege over seasonal labor—a maximalist aesthetic that Ing notes inspired the contemporary designs of Vivienne Westwood. The collection’s three Vermeer's, particularly "Officer and Laughing Girl," offer a different kind of allure through their photorealistic materials and the persistent mystery of their domestic narratives.

Related article - Uphorial Shopify

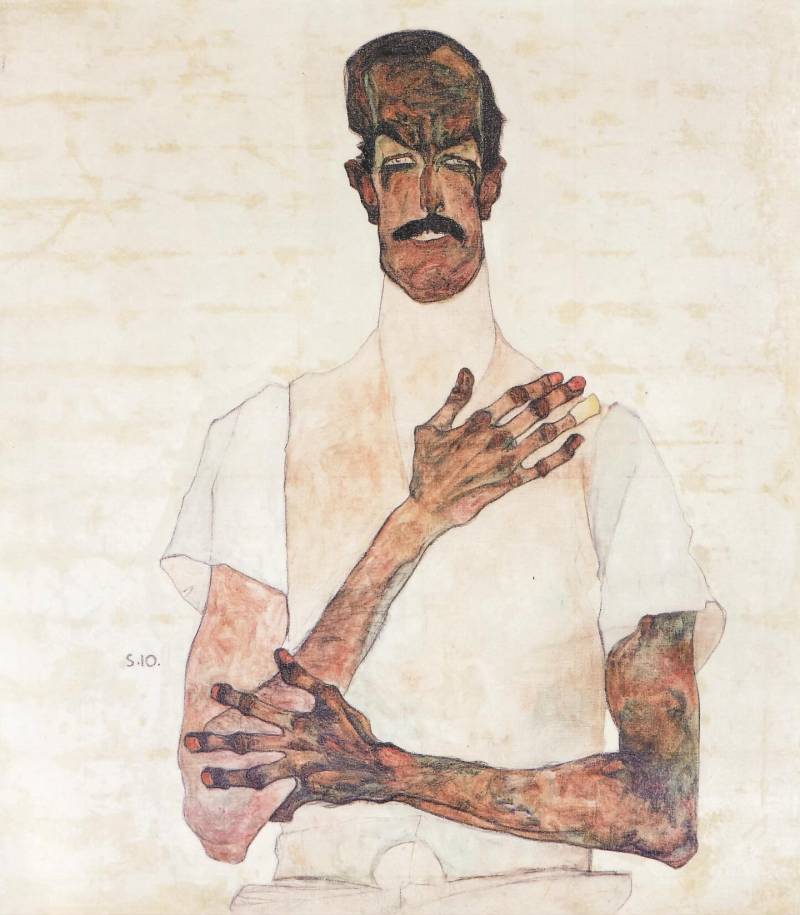

The Frick also preserves artifacts of political and social tension, such as Marie Antoinette’s 18th-century desk, which the Queen insisted be brought to her prison rooms during the French Revolution. In the "corner of power," Bronzino’s portrait featuring a prominent codpiece illustrates shifting standards of morality; the symbol of Renaissance virility was literally painted over by 19th-century censors and only restored to the public eye in the 1940s. This theme of censorship extends to the terracotta sculpture of Diana by Houdon, a figure so delicate it was housed in a protective cage during the building's recent renovation rather than being moved. Even the masterworks are often reveals of deception, such as Rembrandt’s largest self-portrait, where the artist projected the image of a king despite his actual bankruptcy at the time.

For the first time, the public can now explore the mansion’s second floor, walking across seamless rugs and through Mrs. Frick’s boudoir, where the 18th-century French parquet still creaks underfoot. The tour culminates in the Walnut Room, the bedroom where Henry Clay Frick died in 1919 and home to the collection’s "poster girl": Ingres’s Comtesse d'Haussonville.

Ing points out that the painting is a masterpiece of "magic" rather than reality, featuring impossible mirror reflections and anatomical distortions—like an elbow emerging from a hip—to create a perfect illusion. From the mother-of-pearl call buttons for the butler to the priceless canvases, the mansion functions as a single masterpiece where architecture and art are inextricably bound.

Entering the Frick is like stepping inside a layered velvet jewel box; while the individual gems of paintings and sculpture are stunning on their own, the true value lies in how the box itself—the house and its lived history—holds them all in a singular, intimate embrace.