Shakespeare's murderous queen has long been demonised as a wicked seductress. Yet Frances McDormand is the latest actor to show she deserves far more understanding, writes Hanna Flint.

Seductress. Manipulator. Madwoman. The Fourth Witch. These are just a few of the more hostile descriptors that Lady Macbeth has been saddled with ever since The Tragedie of Macbeth (the full title of the Scottish play) was first performed 416 years ago. As a schoolgirl studying William Shakespeare's timeless tale of ambition, morality, betrayal and murder, my first impression was that she was all of the above: a straightforward, out-and-out villain. A wife who, after learning of a witches' prophecy declaring her Scottish general husband would become king, persuades him to commit regicide, take power and subsequently ignites a bloody civil war? Lady M is certainly no angel.

In act five, scene seven of the play, Macbeth's rival for the throne Malcolm declares her a "fiend-like queen," and that label has stuck. The fact that men played female roles in Shakespeare's day likely only compounded this unflattering caricature, but even after women were welcomed on stage, a narrow portrayal of the character has continued. "My experience of Lady Macbeth in the theatre, to begin with, was quite difficult," Erica Whyman, Deputy Artistic Director of The Royal Shakespeare Company tells BBC Culture. "She's cast in the popular imagination as the instrument of evil and that then latches onto stereotypes of women through the ages. It's a caricature of a woman who seeks power through her husband; when you combine that with the idea that she goes mad, you have this toxic combination."

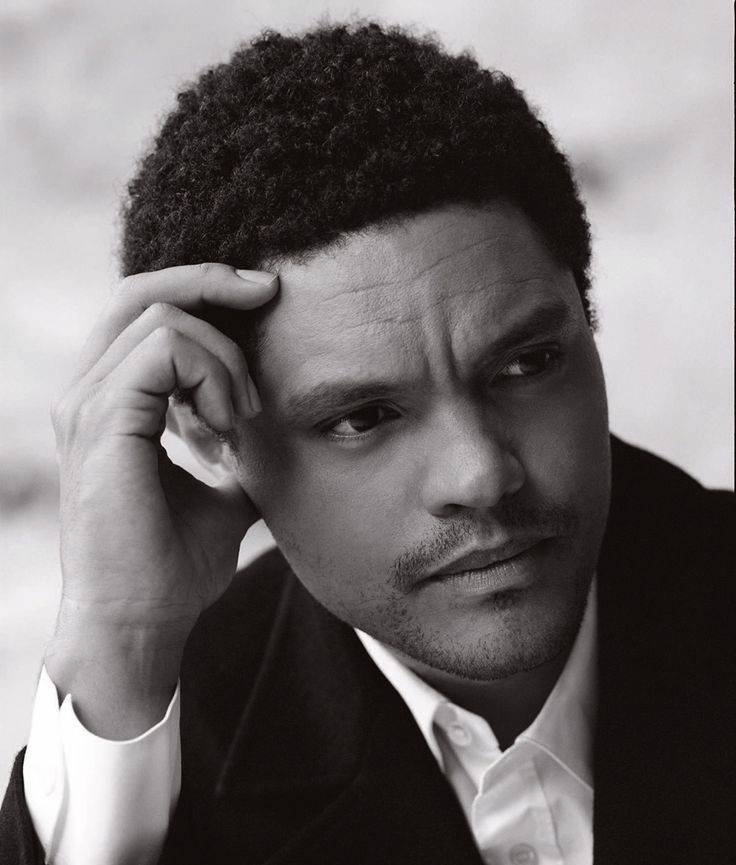

Frances McDormand is the latest actor to play Lady Macbeth on film – and she commands the screen with matriarchal authority (Credit: Apple TV+)

It's this two-dimensional representation that Oscar-nominated actor Ruth Negga is hoping to combat when she takes on the role opposite Daniel Craig in Sam Gold's Broadway production this spring. "I'm very interested in discussing what I think is the long-standing demonisation [of Lady Macbeth]," she tells BBC Culture. "[The play is] a complex excavation of this relationship and desire, fate and power but it feels like we've just plastered it with misogyny. The problem isn't the play, it's the interpretation."

Joel Coen is the most recent filmmaker to have a go at bringing the play to the screen. Released on Apple TV+ on Friday, The Tragedy of Macbeth is a faithful adaptation which keeps the original Shakespearean dialogue, though presents the story in black-and-white using a stylised German expressionist-brutalist aesthetic, with Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand playing the tragic couple. As Lady M, McDormand commands the screen with matriarchal authority. There's nothing hysterical or overtly 'evil' about her performance; rather she plays the character as someone who is determined that their murderous actions are for the good of her hard-working husband, until the guilt becomes too much to bear.

Contemporary feminist readings and criticism have similarly reappraised Lady Macbeth as a far more sympathetic figure than the one that has been traditionally depicted. She might not have been historically perceived as a tragic hero like her husband – and Shakespeare didn't give her as much stage time either – but the play's title speaks to more than just his devastating fall from grace. It speaks to hers too. With this in mind, films and theatre productions have increasingly offered a deeper engagement with her, and with Shakespeare's progressive ideas about gender, motherhood and the patriarchy that are as relevant today as they were back then. "He would not have recognised what we mean by women's rights or what we mean by equality but what he did was treat every human being in his plays as though they had something to say that we should listen to," says Whyman.

The range of Lady Macbeths

One of the earliest portrayals of Lady Macbeth that broke the mould was delivered by Welsh actor Sarah Siddons in 1785 at London's Drury Lane Theatre. In an essay she wrote entitled Remarks on the Character of Lady Macbeth, Siddons viewed her as "fair, feminine, nay, perhaps, even fragile," which is why in her reading, Macbeth was susceptible to his wife's suggestion. "Such a combination only, respectable in energy and strength of mind, and captivating in feminine loveliness, could have composed a charm of such potency as to fascinate the mind of a hero so dauntless, a character so amiable, so honourable as Macbeth," she writes. Her depiction was "tragedy personified," as critic William Hazlitt put it, and starkly contrasted with fellow 18th-Century star Hannah Pritchard's earlier turn which clung to the "savage, demoniac" tradition. Siddons' influence would be felt a century later, in 1888, when stage star Ellen Terry, inspired by an imperative in Siddons' essay to "not hold by the 'fiend' reading of the character," took to the stage at London's Lyceum Theatre. As described by Michael Holroyd in his biography, A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and their Remarkable Families, Terry wrote on the flyleaves of her copy of the play that Lady Macbeth was "full of womanliness" and "capable of affection," adding: "she loves her husband… and is half the time afraid whilst urging Macbeth not to be afraid as she loves a man."

She's got a conscience and is aware of the emotional and moral cost but thinks it's worth putting that to one side. That's always a terrible idea – Erica Whyman

He loves her right back; Shakespeare is always intentional with the words he uses, so when Macbeth calls her his "dearest partner of greatness", it indicates their marriage is bonded by both love, ambition and equality – he calls her his "partner", after all. In Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 film Throne of Blood, which transposes the story of Macbeth to 16th-Century Japan, Lady Asaji's (Isuzu Yamada) love for her husband Lord Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) manifests as paranoia. She argues that news of the witches' prophecy would get back to their Great Lord which would paint them as a potential threat to the throne. "This is a wicked world," she says calmly. "To save yourself you often first must kill."

Coen's The Tragedy of Macbeth also shows a more affectionate relationship between its lead pair. Both in their sixties, the actors are older than your typical Macbeths, but that helps emphasise that the couple's lasting union is one built on years of trust and mutual support. In Lady Macbeth's opening scene, McDormand delivers the line, "Yet do I fear thy nature; It is too full o' the milk of human kindness," with the casualness of a wife who knows her husband better than he knows himself – but her love is most ardent. A warm smile spreads across her sleeping face as she senses the morning arrival of her husband. When Macbeth then whispers "my dearest love", the words are tenderly caressing and the two lovingly embrace. Her expression is a far-cry from the grimace she wore the night before when commanding "spirits" to change her very nature as the couple plot to murder the doomed King Duncan. "Come, you spirits that tend on mortal thoughts," she utters, looking to the sky and briefly to the bed upon which she sits. "Unsex me here and fill me from the crown to the toe top-full of direst cruelty. Make thick my blood; stop up the access and passage to remorse That no compunctious visitings of nature shake my fell purpose."

Ruth Negga is about to play Lady Macbeth on Broadway opposite Daniel Craig – and is keen to redress misogynistic interpretations of her (Credit: Getty Images)

Judi Dench performs this powerful act one speech far more dynamically in the filmed 1979 version of Trevor Nunn's legendary Royal Shakespeare Company production, in which she starred opposite Ian McKellen. Dropping to her knees with her hand outstretched, she begs for the constraints of her gender to be removed then suddenly jumps up with a squeak as though the spirits had answered her call. Returning to the floor, she completes her whispering invocation in climactic fashion: "That my keen knife see not the wound it makes, nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark to cry 'Hold. Hold!'"

Though painstakingly delivered, Dench's version reinforces the sorceress-like stereotype of Lady Macbeth, as though she has conjured these spirits to help do her work. By contrast, McDormand's resolute poise and level intonation avoids making the supernatural metaphor appear so literal and refutes any interpretation she could be the Fourth Witch using dark magic to manipulate her husband.

Performed in this manner, the speech simply reinforces Lady Macbeth's commitment to Macbeth's desire to rule. It also lays bare the gender politics within the play's society. Femininity is seen as a weakness, masculinity is associated with cold ambition, and Lady Macbeth recognises too much of the former in both herself and her husband. "'Unsex me here,' is this idea that her sex is not useful to her at this moment," says Whyman. "'Stop up the passage to remorse' is a peculiarly evocative image for a woman; to use this idea of not being an open vessel and instead be strong, closed and steely. She's got a conscience and is aware of the emotional and moral cost but thinks it's worth putting that to one side. That's always a terrible idea.'"

The notion that if femininity is removed from this world, bad things happen, is something that Whyman identifies as a recurring theme in the English playwright's work. "The feminine to Shakespeare means an understanding of compassion, and understanding that we need to live in a community and family, rather than each individual's ambition leading us towards the definition of success," she says. "He's constantly guarding against or warning us against eliminating the feminine – if Macbeth was allowed to be feminine, he wouldn't have killed."

What are Lady Macbeth's motives?

Another reading of Lady Macbeth's motivations is that of a childless woman seeking glorious purpose: if she cannot secure Macbeth's legacy with an heir, she can through the throne. The primary role for a woman was bearing children, and the child mortality rate in Shakespeare's time was around one in three, so it's unsurprising he heavily implied the couple lost a child. "I have given suck and know how tender 'tis to love the babe that milks me," says Lady Macbeth in act one scene seven. When that death occurred is unclear, but filmmaker Justin Kurzel made the event literal in the opening of his 2015 adaptation, starring Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard, with a scene where the anguished Macbeths attend the funeral of their toddler. The fog of grief clouds their battlement and their judgement, something Kurosawa also suggested in Throne of Blood by having Lady Asiji give birth to a stillborn child which influences Wasizu's decision to assassinate both his best friend Miki and his son who "one day shall rule Spider's Web Castle".

Macbeth’s in his prime, is at the top of his game, whereas Lady Macbeth is perceived as past hers. 400 years later, there's still a bit of that – we start to find women invisible – Erica Whyman

But in Kurzel's film, he emphasises the theme of a mother's loss, in particular, to the point of turning Lady Macbeth's climactic sleepwalking scene in act five into a heart-breaking church confessional in which she speaks to a vision of her dead son. More overstated direction could have led to this moment merely affirming the perception of Lady Macbeth as a mad woman but instead Cotillard's delivery of her lines is restrained, showing that subconsciously or not, the passage to remorse has flooded open. She keenly feels the guilt for her wicked deeds but the ghostly presence of her child in this scene suggests she is also pained by her earlier declaration that she would have killed him to achieve their goal: "Have pluckd my nipple from his boneless gums and dashd the brains out, had I so sworn as you have done to this."

Both in Coen's film and the Royal Shakespeare Company's 2018 production, starring Christopher Eccleston and Niamh Cusack as the Macbeths, their loss appears less recent and Lady Macbeth is far past the point where she could conceive – which makes her appear more disposable within the world of the play as Macbeth begins to distance himself from his wife. "This brilliant, intelligent, quick-thinking, courageous woman is confined to a ceremonial role that comes through very strongly when it's an older couple," says Whyman. "Macbeth's in his prime, is at the top of his game, [whereas Lady Macbeth is perceived as past hers]. 400 years later, there's still a bit of that – we start to find women invisible. We don't notice their sexual charms so much and don't see them as sexual beings."

By contrast, younger casting often goes hand in hand with an amping up of the passionate sexuality and desire in the Macbeths' relationship – but done right, that doesn't mean Lady Macbeth has to occupy the wicked seductress stereotype. In Kurzel's film, the Macbeths enjoy a sensual sex scene in which Lady Macbeth persuades her husband to carry out their treacherous plan. Had attention not been paid to her role as a mother, a partner and her mental health as a whole, Cotillard's iteration might have fit that reductive characterisation. Whyman points to Saoirse Ronan's performance in the recent production at London's Almeida theatre as another fine example of a younger take on Lady Macbeth: "It was full of life and sexuality. I found it very moving because theirs was a love affair that was so damaged by violence. There's one decision, whatever the chain of events, that destroys that forever."

In Justin Kurzel's 2015 film, with Marion Cotillard and Michael Fassbender, it is made clear that the Macbeths are anguished by the death of their child (Credit: Alamy)

That fateful choice, in Lady Macbeth's case, may be best understood as that of a woman navigating a strongly patriarchal world. If women had ambitions in early modern England, they mostly had to accomplish them through men, and there's a strong sense that Lady Macbeth missed an opportunity to achieve greatness both because of her sex and her husband – Macbeth might have status on the battlefield but has less so in court. Her questioning of his manly courage ("Art thou afeard?") cannot simply be viewed as emasculation but an indication that she could have married a man with more political power. "There is a really interesting theme that there's a different tragedy for Lady Macbeth when she's [played] older – she could have easily been queen," Whyman says. "[Shakespare is] consistently curious about what it is to be a female leader and he keeps putting these guys up with deep flaws, and then suggesting there's a woman close to them who could have done it better. Of course, he was also living through a time where the idea of a queen was very potent." Whyman points to Hermione in The Winter's Tale as another of Shakespeare's women who suffers at the hands of a weak-minded husband. The virtuous Queen of Sicily is falsely accused of infidelity by King Leontes and is forced to stand trial: "Queen Hermione is treated appallingly [but] she would have led the country brilliantly.

King James I might have been the British sovereign when Macbeth was published but his predecessor, Elizabeth I, was an obvious influence on Shakespeare. Upon her ascension to the throne, the monarch challenged gender roles; she refused to submit to marriage – arguing she was "already bound unto a husband, which is the kingdom of England" – while clinging to her feminine identity in her aesthetic and various speeches, describing her subjects as her "children" for example. But she also displayed the royal traits (considered masculine because of the traditionally male hierarchy) of active agency and decision making, and was referred to using royal male descriptors, like "princely" and "Prince of Light" , as well as being classified as "king" in Parliamentary statute for political purposes. However, where Elizabeth I embraced political androgyny and reigned for 45 years, Lady Macbeth unsexes herself and loses her way. "She thinks the only way to get success is to follow a set of rules that are patriarchal," says Whyman. "She's not a kind of power-hungry, man impersonator – she's wholly in her skin, but she does think the only way to have agency in the world is to do this terrible deed and she's quite wrong about that. If she held onto her morals, so her femininity in that sense, it wouldn’t have happened."

Shakespeare was miles ahead when it came to female representation and Lady Macbeth is a character that has too frequently been painted in a two-dimensional light. Had she been afforded more scenes in the play, her motivations might not have appeared so ambiguous to narrow-minded viewers. As it is, Lady M exits the play after her sleepwalking scene and in act five scene seven is reported as dead, evidently by suicide if Malcolm's comment that she "by self and violent hands took off her life" is to be believed. But Coen complicates things by adding a sequence involving Lady Macbeth and nobleman Ross (Alex Haskell) that suggests even more foul play might be involved. Did she throw herself down the stairs – either because the guilt was too much or as an act of atonement – or was she pushed by Ross as revenge for her husband's order to murder his cousin Lady MacDuff? That's up to the viewer to decide. What is clear, is that Macbeth cares for his wife until the end and Coen presents this by having Washington's tragic hero looking down upon her laying at the bottom of the fateful staircase, staggering slightly as the pain washes over him. The one constant in this adaptation is their love for one-another.

McDormand joins a welcome list of women bringing enough depth and layers to this formidable character to combat 400 years of gross misunderstandings that say more about those interpreters than the multifaceted literary figure Shakespeare created. Lady Macbeth is a timeless, tragic heroine who should be cherished not scorned. "It's unhelpful to portray her as wicked or to suggest that because she hasn't got a child she's, in some ways, hollow and barren and inevitably evil," says Whyman. "She’s not a villain; she’s complex, she's curious – we should admire her."