In 1879, Spanish aristocrat and amateur archaeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuloa and his daughter Maria set out to explore a cave near their family home in Cantabria. While De Sautuola scrambled around the floor looking for prehistoric artefacts, Maria wandered off deeper into the cave. Suddenly she stumbled across a ceiling covered with dozens of paintings. The drawings were of aurochs, a long extinct species of ox. They were painted by the Magdalenian people between 14,820 and 13,130 years ago.

At the time scholars were surprised that early humans were capable of artistic expression, but the origins of art stretch much further back than this. In fact, art predates the existence of Homo sapiens altogether.

Some 51,000 years ago, a Neanderthal carved patterns into a deer bone in a cave in Germany. The carving was made several thousand years before Homo sapiens arrived in Europe. Meanwhile 500,000 years ago, Homo erectus, an even more primitive species of human, etched abstract zig-zag lines into a seashell in Java.

These findings challenge the belief that art is the special provenance of Homo sapiens, but it is perhaps not that surprising that other species of human had creative impulses. After all, we know that other hominins made and used tools, and even buried their dead.

However, it may surprise you to learn that there are other members of the animal kingdom that appreciate beauty and artistic flair too.

You might also like:

Why animals love touchscreens

The animals changed by proximity to humans

Why do cats purr?

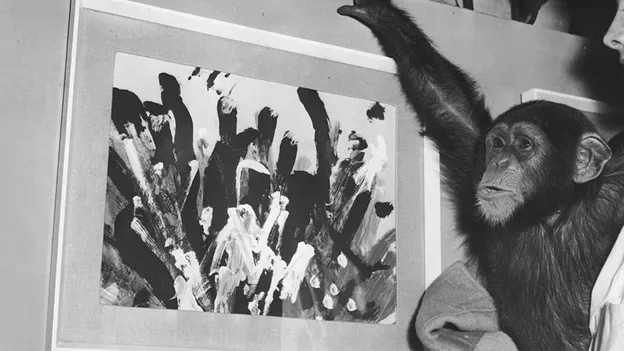

In 2005 a set of three paintings by a chimpanzee called Congo were sold at auction for £14,400 ($18,122). Congo was born in 1954 at London Zoo, and while he was there he caught the attention of British zoologist and artist Desmond Morris. Morris gave the chimp a pencil and some card and was amazed when he started drawing. Over his lifetime Congo created more than 400 works, some with pencils and others with paint.

While his works were abstract – he never painted identifiable images such as portraits or landscapes – he approached his work with a sense of intention, and if his paintings or brushes were taken away he loudly complained until they were handed back to him. If he felt he had completed a work he would refuse to amend what he had done. What's more, over the years he advanced from scribbly lines and splotches of paint to more carefully considered compositions. It's said that Picasso reportedly owned a painting by Congo and hung it in his studio.

But how can we tell that the drawings made by Congo were truly art? Elephants in captivity have been trained to create artworks, but in the wild they have no interest in painting flowers or still life. Do chimpanzees find meaning or purpose in putting pencil to paper?

To understand whether animals really can appreciate or produce art, we need to know what art actually is. However its definition varies immensely.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines it more in terms of skill:

"The application of skill to the arts of imitation and design, painting, engraving, sculpture, architecture; and the skilful production of the beautiful in visible forms."

While the Collins English Dictionary emphasises the purpose behind its creation:

"Paintings, sculpture, and other pictures or objects which are created for people to look at and admire or think deeply about."

There are many animals that make elaborate structures, but almost all of this output serves a practical rather than aesthetic purpose. Spiders weave intricate webs that look beautiful to the human eye, but to the spiders they serve as fly traps. Architects looking for a bold innovative design need look no further than the perfect symmetry of the honeycomb, but bees use it to house their larvae and stores of honey and pollen.

Nevertheless, there are some creatures that create objects of beauty without any seemingly practical purpose.

In 1995, divers off the coast of Japan noticed a series of odd geometric patterns etched on the seafloor. These "underwater crop circles," as they became known, stretched up to 2m (6.6ft) long, and remained a mystery for almost two decades.

In 2011, scientists found the creature responsible – a new species of Torquigener pufferfish. The male pufferfish painstakingly creates the circles by flapping his fins as he swims along the sea floor. He then gathers fine sand to give the sculpture a more vibrant look and colouring. Finally, he decorates the ridges and valleys within the circles with fragments of seashells.

The sculptures take up to nine days to construct, and after they are finished females come to inspect them. If they like what they see, then the females lay eggs in the centre of the circle for the males to fertilise.

So far, no functional or adaptive purpose for the circles have been found, suggesting that the females could simply be attracted to the aesthetic beauty of the geometric shapes.

Pufferfish, it turns out, aren't the only animals to create interesting sculptures.

In 1872, the explorer Odoardo Beccari became the first European to climb the Vogelkop mountains of New Guinea and meet members of the Arfak tribe. While there, he observed a series of beautifully decorated huts in the forest which he assumed were the work of the villagers. In front of each hut was a little garden decorated with moss and more than a hundred colourful objects including fruits, fresh flowers, mushrooms and beetle skeletons.

Remarkably the beautiful huts were not constructed by humans at all, but rather a bird - the Vogelkop Garden Bowerbird to be precise. Since then more than 20 species of bowerbird have been discovered in Australia, New Guinea and the nearby islands.

In each case the males of the species build beautifully decorated structures, known as bowers, to entice females. The bowers consist of tall avenues of densely thatched sticks woven together with moss. The avenues open onto larger flat areas or courts which are adorned with shells, acorns, fresh fruits, flowers and even sometimes butterfly wings. Bowers located near to human villages can be adorned with items such as car keys, bottle tops, toothbrushes, spectacles and false teeth. Some species of bower bird even paint their bowers using crushed fruit, charcoal or even laundry powder stolen from nearby human habitats.

The females inspect the bowers before choosing their favourite, but what exactly are they looking for?

"One aspect is the shape and the size of the avenue, and also the number of ornaments and the visual contrast between them," says John Endler, evolutionary biologist and emeritus professor at Deakin University in Australia.

The regular geometric patterns and avenues could also create an optical illusion known as forced perspective. which could serve to attract the female's attention.

"The male also performs a kind of visual display where he moves colourful objects quickly across the female's visual field so they see it quickly and then it disappears," says Endler.

"All these sorts of interesting visual effects serve to attract and hold the female's attention."

So does this prove that bowerbirds have an aesthetic sense?

It's certainly true that individual bowerbirds have their own tastes and preferences when it comes to materials and colour. Each item is placed with great care and precision, and if any objects are moved the birds return them to their original place. Younger birds also appear to learn how to build the most attractive bowers, either through trial and error, or by watching more experienced birds. Bowerbirds also spend a great deal of time and effort building their bowers and defending them from rival males.

Appreciating art

While the list of creatures who produce art is relatively small, there are other animals who, it could be argued, seem to appreciate beauty.

In 1995, a team of psychologists led by Shigeru Watanabe, a professor of psychology from Keio University in Tokyo, showed that pigeons could be taught to discriminate Claude Monet artworks from Pablo Picasso.

Further research found that koi fish were capable of distinguishing the music of blues singer John Lee Hooker from that of Johann Sebastian Bach. Goldfish can also be taught to distinguish between Bach and Igor Stravinsky.

However, this simply shows that animals can be trained to differentiate artworks. It doesn't prove that they appreciate or gain pleasure from them.

Nevertheless, a separate study by Watanabe seemed to suggest that birds can experience pleasure from art. He found that, when given the choice, individual Java sparrows prefer to spend time perched near specific paintings. Five out of seven sparrows demonstrated a preference for Cubist paintings over Impressionist artworks, while three also seemed to prefer Japanese paintings over impressionist pieces.

"As we can't ask animals whether they enjoy or find pleasure in art, in experimental psychology we look a property called reinforcement instead," says Watanabe.

"If an animal does something in order to see art or to hear music, then that art and music must have reinforcing properties."

"Many species of birds, mammals and even fish can discriminate between different paintings or pieces of music, but few find them reinforcing."

Monkeys may be one such group. Humans often prefer symmetrical patterns to random ones, and it turns out that certain species of monkey do too. In 1957 German biologist Bernhard Rensch presented capuchin monkeys with small squares of cardboard showing either symmetrical patterns, such as parallel lines or concentric squares, or "irregular patterns of similar black and white content". Over hundreds of trials, the capuchin showed a significant bias for picking up the patterned cards. Rensch believed that this was because the monkeys possessed "certain basic aesthetic feelings".

Another species that does appear to appreciate beauty and aesthetics is the peacock. The peacock's tail is useless for flight. It is so large that it is a physical burden to carry around. It also is more likely to attract the attention of predators. Nevertheless, if a male is to have any hope of attracting a mate he must invest in the costly, brightly coloured plumage. Why? Because female peahens find it sexy. The preference is so strong that it is a major driving force of evolution in the peacock, leading to more extravagant tail feathers over time.

But this still doesn't really answer the question of why the females are drawn to brightly coloured objects, or symmetrical geometric designs. What possible evolutionary benefit could it serve?

One idea is that humans, monkeys and even sparrows are attracted to some kinds of art because they remind them of their natural habitat, or because the art might provide cover and so make them feel more secure.

"Our sparrows preferred Impressionist paintings to Cubists so we can say they liked more natural paintings, but more research is needed to confirm this", says Watanabe.

The strongest and fittest bowerbirds may build the best bowers

Another theory is that the brightness of the peacock's spots, or the ornately coloured bowers, could serve as indicators of strength, or "good genes" in the male. Male bowerbirds spend a huge amount of time protecting their bowers from rival males, whilst simultaneously attempting to steal ornaments and destroy the bowers of other birds. One study showed that out of 100 pieces of blue glass placed in the bower of a subordinate male, 76 had been transferred to the bower of a more dominant male within a day. That suggests that the strongest and fittest bowerbirds may build the best bowers.

However, this isn't the whole story.

"The other alternative hypothesis is that females of some species have an innate preference for high visual contrast and bright colours, and so the males have evolved to take advantage of this by building more and more elaborate bowers or investing in bright plumage," says Endler.

This is kind of a revolutionary idea, because it suggests that it isn't just a case of survival of the fittest. It leaves us with the question – could animals' (and particularly females') appreciation of art, beauty and aesthetics actually be a driving force of evolution?