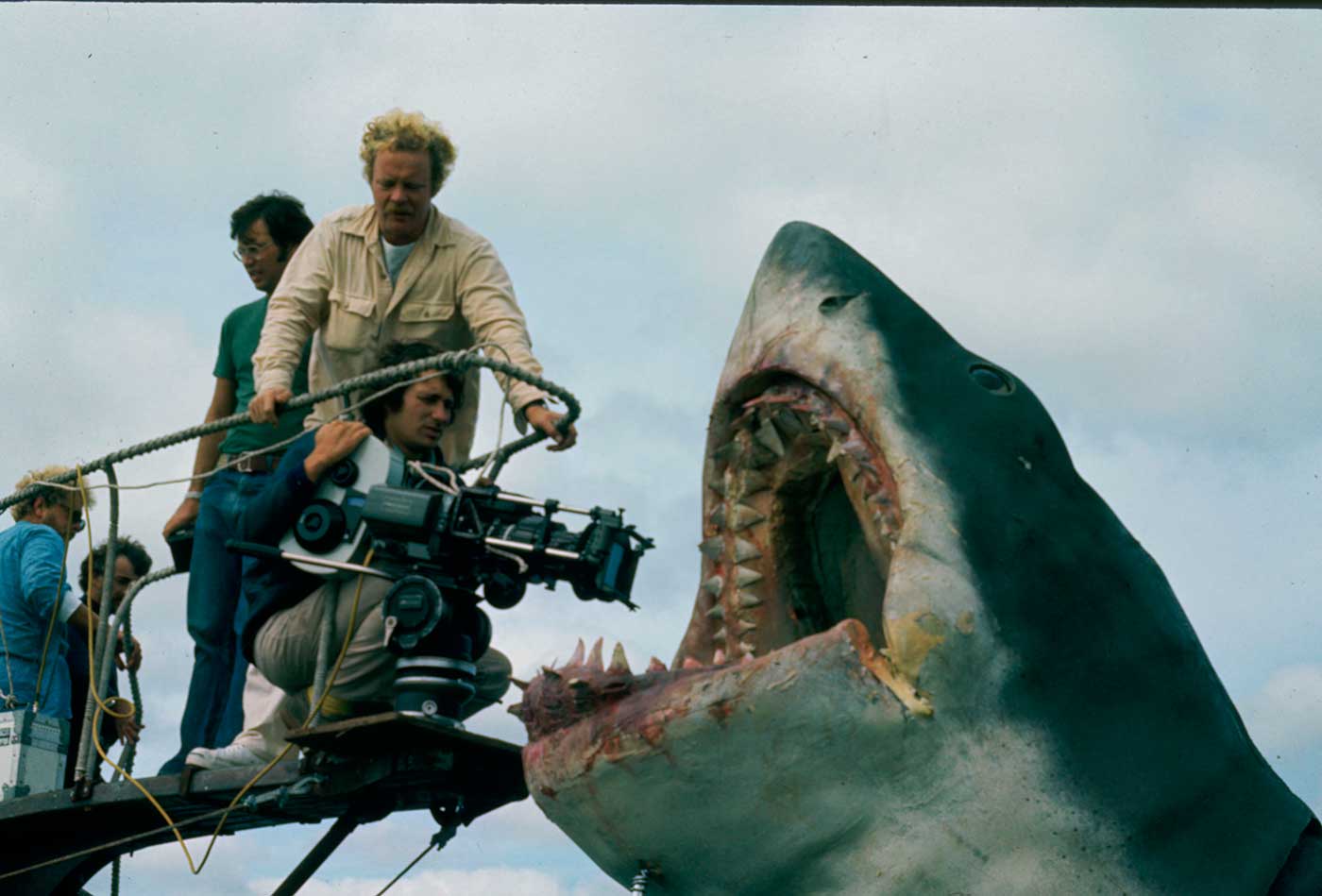

Everything necessary to summon a moment feeling of risk in any individual who has watched Jaws is two notes, a semitone separated, cunningly sent to demonstrate the looming danger of an extraordinary white shark. However, presently, almost 50 years on, chief Steven Spielberg has yielded that maybe the Oscar-winning 1975 spine chiller was excessively successful at conjuring dread of the slandered animals, conceding he is "genuinely remorseful" for any impact he has had on the world's quickly contracting shark populace. Since the mid 70s, the total populace of maritime sharks and beams has fallen by 71% because of overfishing, a worldwide report distributed in Nature tracked down a year ago.

Spielberg tells of guilt over harm hit film Jaws may have done to sharks Director tells BBC’s Desert Island Discs he regrets the ‘frenzy of sport fishing’ that followed 1975 thriller’s release A scene from Jaws Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw in a scene from the Oscar-winning Jaws. Photograph: Universal/Allstar Miranda Bryant Sun 18 Dec 2022 04.29 EST All it takes to conjure an instant sense of danger in anyone who has watched Jaws is two notes, a semitone apart, ingeniously deployed to indicate the impending threat of a great white shark. But now, nearly half a century on, director Steven Spielberg has conceded that perhaps the Oscar-winning 1975 thriller was too effective at conjuring fear of the defamed creatures, admitting he is

“truly regretful” for any influence he has had on the world’s rapidly shrinking shark population. Since the early 70s, the world’s population of oceanic sharks and rays has fallen by 71% as a result of overfishing, a global study published in Nature found last year. “I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really, truly regret that,” the American director tells Desert Island Discs, to be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Sunday. Asked by presenter Lauren Laverne how he would feel about having sharks circling him if he were sent to the show’s imaginary desert island, the 75-year-old said: “That’s one of the things I still fear. Not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me for the feeding frenzy of crazy sports fishermen that happened after 1975.”

While demand for shark fins has shrunk in recent years, the desire for shark meat is on the rise. Where Jaws may have had an impact, however, is in clouding the messaging around sharks, Cox said: “It has led conversations into a bit of a trap in spending too much time talking about all the things that sharks aren’t rather than all the great things sharks are.” He is, however, grateful for the positive PR that Spielberg’s comments offer. “For someone with his celebrity to be addressing the challenge of communicating about sharks in a more positive way is very welcome.”

The film exploits a pre-existing fear, he said. “It’s a natural fear we have of the unknown. The sea, the marine environment, still has a lot of unknowns.” Christopher Paul Jones, a Harley Street phobia specialist, is convinced of the film’s power. Most of the people he encounters with galeophobia, or fear of sharks, go back to films such as Jaws because most people have never seen a shark except in an aquarium. “It’s testament to the way it was done. You can’t see below water, and the music creates a sense of fear,” he said. “Movies are very good at hitting every sense – visual, sound, and can be very impactful on how we feel.” He said that films such as Jaws are often “the seed of the emotion”. “People will come to me – it might not be a fear of sharks but a fear of swimming or water. When you look at how it started, it can be Jaws.” In another Desert Island Discs confession, Spielberg said that film-makers should not “manipulate” audiences by playing on their emotions, but admitted that he had been guilty of it in Jaws. “A film-maker must never manipulate the audience unless every single scene has a jack-in-the-box kind of scare. That’s manipulation,” he said. “I did that a couple of times in Poltergeist and I certainly did it once in Jaws, where the head comes out of the hole. That’s OK, I confess that.”