The Nigerian artist created his own Afrobeat brand, Afro-Rave, but claims it's just part of a broader movement to bring African music to the West. It's clear his ambitions are global as he prepares to host his singles show, which debuts in the UK in September.

Read Also: What's New And Black Showing On Netflix In September

Despite famously singing “I’m in love with plenty women”, Rema reports having no current romantic interests or any room in his life for dating at all. “I don’t have time for it, I have a world to take,” the 22-year-old says in an accent which seems to straddle Benin City and Atlanta. When you consider that his career is taking off, it’s no surprise.

When we speak over a video call in June, the golden child of Afropop is resting after a heavy week of shows in Oslo and Geneva, and gearing up for a performance at London’s Wireless festival in Finsbury Park. In September, Rema will perform his debut solo UK concert in London before setting off on a tour of the rest of the UK and Europe. Artists have greater creative licence when staging their own shows and this prospect excites him.

“It’s full-on Rema,” he says, his soft, low, humming voice breaking into bold intonation. “It’s big for me, it’s always been a dream. I feel like my fans out here in the UK, they have wanted this for a long while. I’m glad I’m going to be able to bring my own ideas and carry my full team on stage, including my band, because sometimes it’s hard with all these festivals, based on the fact they have a lot of artists and need to make provisions for a lot of people.”

Born Divine Ikubor, Rema grew up in Benin City, the capital of the fallen Benin Empire now located in Edo State, present-day Nigeria. Benin City has a rich history, famed for its bronzes, earthworks and powerful obas (rulers), but also for its varied religions, a feature which, Rema says, persists today. He notes how Benin — which he correctly pronounces “Bini” — is deeply spiritual. “It’s a place in Nigeria where the traditional rule holds more ground than the government,” he tells me. “There is huge diversity of religion. There are small communities with their own twist to the Benin language. Everyone knows each other, but everyone doesn’t know each other. It’s the culture which brings people together.”

He also describes Benin as a place that is “fearful” of change, but which endowed him with a rich, intense education that he only became aware of once he left. Although he speaks nostalgically of growing up in the city, Rema left the capital for Ghana when he was 17 years old. “Things were tough in Benin,” he explains, “I had to find bread for my family. I ran away from home because we were facing a lot of issues and I had to make ends meet.”

He is reluctant to detail the problems that affected his family, but in 2008, his father, Justice, a politician in Nigeria’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP), was found dead in a hotel room in circumstances that are still unknown. This loss brought financial pressures for the family. In 2020, Rema called the party out, saying, “PDP, y’all need to explain what happened to my father in that hotel room. Justice Ikubor’s son has risen.” In the same year, Rema spoke out about his older brother dying years earlier due to negligence in the Nigerian healthcare system. Their deaths left him as “the only man, needing to do something”, so he relocated to Ghana. Taking a break from music, he carried out hard labour.

“All we’re here to do is take our culture and spread it to the world and attract people back to their roots”

— Rema

Such turmoil would curtail the aspirations of even the toughest person, which makes it all the more remarkable that Rema has made such a success of himself and become a global name. With messianic zeal and gratitude, Rema reflects on the “timing” of his “come up”, sharing that “God made it happen now, because I am so right for this time”, as we discuss how Nigerian Afrobeats and Afropop music are currently dominating the charts as well as day parties and festivals in the West. At a day party like DLT Brunch, frequented by Black Brits in London, you could expect to hear Rema’s ‘Bounce’ mixed alongside Wizkid’s ‘Anoti’, Asake’s ‘Palazzo’, and Burna Boy’s ‘Last Last’. It’s enchanting, soulful music which sends hips swinging, booties low, and throws both gun fingers and gospel hands in the air. These are sounds which resonate across the African diaspora for their effortless linguistic blending of English, Yoruba, pidgin and, in Rema’s case, Edo language. And the rapper feels that he’s but one soldier working collaboratively as Afrobeat advances in its cultural domination of the West.

“It’s a blessing. And never will I ever carry that competitive mindset,” he asserts. “All we’re here to do is take our culture and spread it to the world and attract people back to their roots. I’m grateful and I’m really proud of what the legends have done before me, and I’m graced by the fact that I’m also creating a fine ground for the next generation after me.”

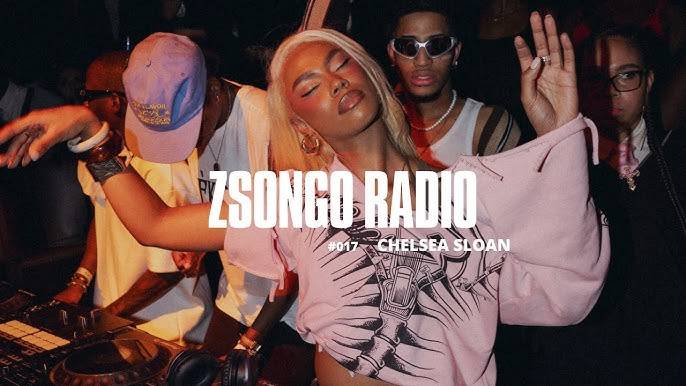

Rema wears jacket by Palace, bandana by ASOS, bracelet by Pawnshop (Picture: Shenell Kennedy/Styling: Joseph Kocharian)

The increased popularity of Afrobeat music, however, does not mean that it is homogeneous — in fact, Rema is perhaps the truest testament to the diversity of Nigerian music. West African artists frequently encounter interrogations over their genre and comments that their music is ‘unplaceable’, but Rema has distilled his own sound into what he terms “Afro-rave”. When I ask him to define it, he tells me to wait a moment while he retrieves a note on which he has written the definition. He then reads it aloud: “Afro-rave is my perception of Afrobeats, it’s a sub-genre. It includes the melody, delivery and diversity and its flexibility to maintain its own stance, sound-wise, in any beats pattern and outside Afro. So yeah, that’s Afro-rave.”

It’s a genre that wasn’t immediate to the artist, as his journey through musical styles has been varied and plural. Looking back on his youth in Benin City, he remembers that he had neither a musical device of his own nor the money to purchase what he wanted to listen to, so he’d tune into what his family played. “My mum was big on gospel music, my sister was big on love songs, and also Michael Jackson, Wizkid, R&B, Drake,” he recalls. “My brother used to listen to rap and Burna Boy and Davido — so African music. And my dad was big on legends like Osayomore, and also D’Banj and Don Jazzy, Two Face, Fela. So, I literally grew up listening to what everybody listens to.”

When he began rapping and developing his own melodies as a teenager, he was first attracted to hip-hop, lo-fi music, and also a lot of rock songs that have since imprinted on his own discography. He turned to SoundCloud to be introduced to new forms of music and would “listen to whatever playlist my mood was feeling”. He came across the likes of Daft Punk, Travis Scott and Kid Cudi. “I started to listen to a whole different field of music and started creating my own perspective, and then just kept going on from there.

“I listen to a lot of alternative music,” he continues. “I don’t know the names [of the artists], some of them just wrote two songs and then just [ghosted]. But when I was growing up, I couldn’t know the words because I didn’t have a device to play off of to know them, so I usually just hummed them, so that’s something which influenced my music because I hum a lot in my songs.”

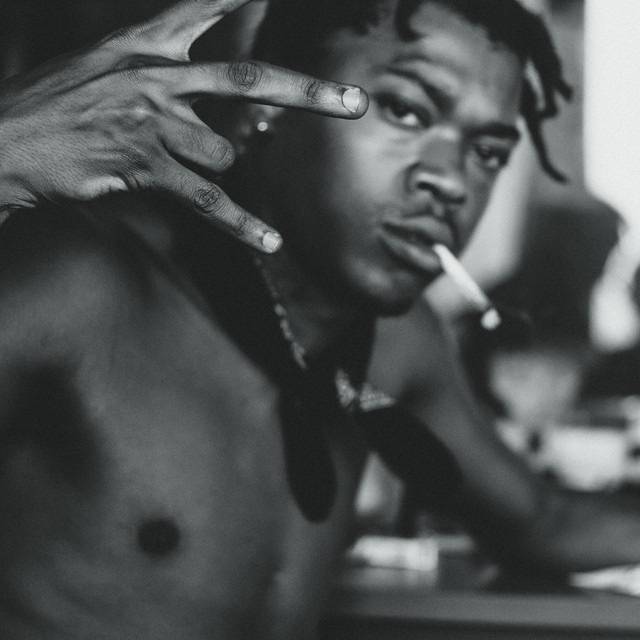

Rema wears jacket by Balmain, top by Tommy Hilfiger, jeans by Balenciaga at END., bracelet by Pawnshop, trainers by Converse (Picture: Shenell Kennedy/Styling: Joseph Kocharian)

eing a rapper, it wasn’t obvious to Rema that he could melt his vocals over an Afrobeat sound, but when he was discovered and offered a record deal by D’Prince in 2018 after his Instagram post freestyling over the singer’s ‘Gucci Gang’ went viral, Rema was steered towards this style. He now cites this as the “opportunity of a lifetime”.

“He told me that he likes my voice, and he feels like I’m gonna sound really good on Afrobeat,” says Rema. “I told him I don’t really do Afrobeat, I just rap, so he said, ‘Give it a try.’ I was like, ‘This is a mountain I have to climb.’ I kept pushing myself, connecting my influences within. And I made a couple songs and kept going until I found myself, and that’s it. That’s how the Rema sound came out.”

Although his success feels effortless now, Rema wasn’t an overnight sensation — his achievements have been the result of plenty of trial and error. Today, Rema likens himself to an underdog who has beaten the odds to become venerated and worshipped for his uniqueness. “At first it was quite funny, a lot of people laughed, a lot of people criticised, but I stood beside it, I kept going, I kept pushing. Right now, that criticism is a blessing to me: I stand out, I’ve distinguished myself. If I don’t drop music for a year, it will be obvious in Africa that something is missing. That’s how bold a statement my sound has made.”

The infectious Rave & Roses, Rema’s debut album released in March this year, certainly justifies the scale of self-belief. After a 2019 victory lap of three EPs, the full-length record has a youthful, cheeky, sun-dappled, atmospheric quality, conjuring images of boys running around the burnt orange, sandy streets of Nigeria. Much of it introduces listeners to Rema’s life pre-fame, too. On ‘Runaway’, Rema touches on the pressures of pursuing romantic love in Benin City, where boys are hustling and economic anxieties anchor priorities. “Many get money pass me die / But this my baby no dey collect all their bribe”, he sings. Dissecting the meaning of the track, Rema explains: “When I was in Benin, there was a standard that everyone had on relationships, and I felt the need to match up with that because at some point in time I’d be doubting myself or she’d be doubting the relationship — if she’s with the right person and all. And it just caused that paranoia and anxiety, and I felt the need to run away, go somewhere else where we can just create our own narrative of love.”

“Love has played a lot of role in my life, love has been my drive, love has stood as something that grants me healing”

— Rema

Love and its dreams and fantasies are laid out in each track like a divine, romantic offering. On ‘Mara’ he sings, “Girl, you the reggae to my blues, baby / You be my booze”. Despite his earlier confession that he has no time for dating, it does not mean that his life is absent of love or that these themes are false advertisements within his music. Rather, love frames the entirety of his interactions, and both his personal and professional journey. Poetically, he speaks with anaphoras: “Love has played a lot of role in my life, love has been my drive, love has stood as something that grants me healing. Love has given me reasons to live. And it’s not just about a girl, it’s just in general, in life, team-wise, family, everything.”

Compiling this album, then, was a curation of love songs, “When I step in the studio, I just do whatever I feel, and when I feel like all the different songs correlate with each other, I put them together and build them from there. That’s how I created this project, it’s mostly love-based, but it touches on other topics as well. It doesn’t mean I’m a womaniser type; that’s not my aspiration, it’s just that love plays a huge role in my life. That’s the push.”

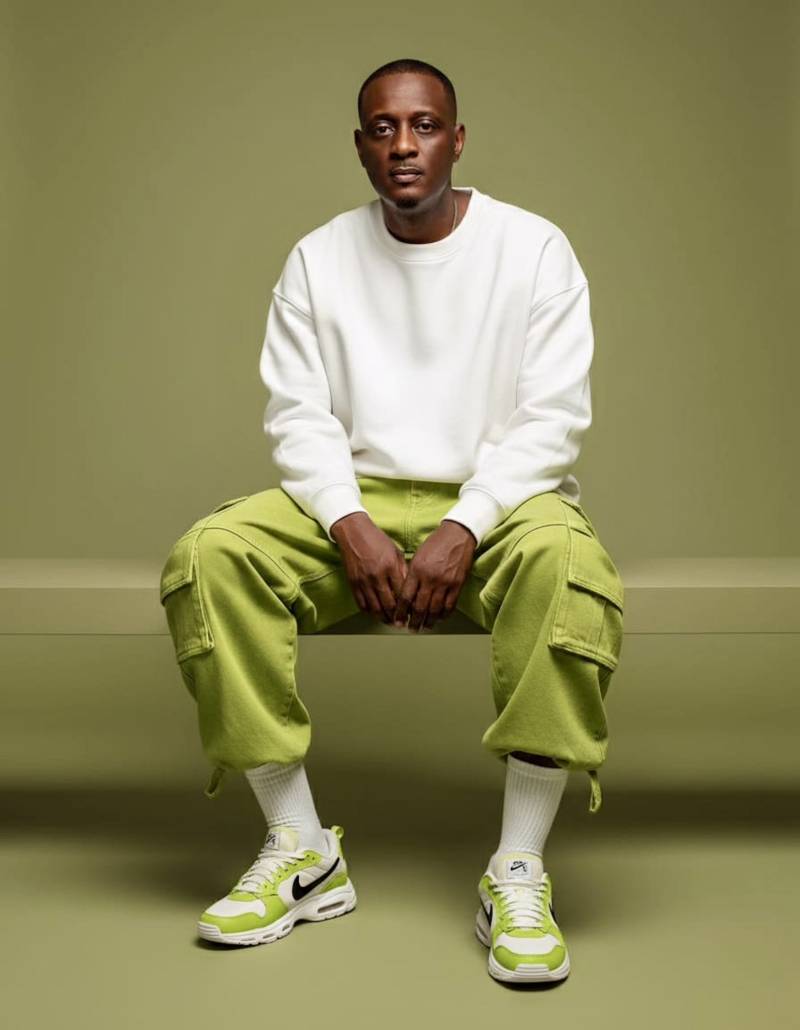

Rema wears jacket and jeans, both by Balenciaga, tank top by Rufskin, bandana by ASOS, sunglasses by Oakley, bracelet by Pawnshop, trainers by Converse (Picture: Shenell Kennedy/Styling: Joseph Kocharian)

Rema feels that this album is like his ‘child’. “It’s very important to me and to Afrobeats and the new generation,” he says. “I feel it’s doing what it’s supposed to do and this was the right time.” Sensing that he is part of a broader shift, one that has been influenced by past generations and will shape the landscape for forthcoming artists, there is a cosmic faithfulness to Rema’s words which is at once humble and confident.

He may just be speaking to a journalist on a video call, but it feels as though Rema is a million miles away — watching ocean waves crash, perhaps, or trees swaying in a rainforest. Or maybe he is staring into the night sky in awe and wondering at the world and its limitlessness. “I feel like it’s high time the youths have something new to believe in, a new religion,” he muses. “And I’m ready to take it up.”