Stepping into Eritrea, a nation off the east coast of Africa, is to enter a realm described by traveler Drew Binsky as "perhaps the weirdest country I have ever visited," a place inherently "cut off from the rest of the world". The initial encounter sets the tone: an arrival marked by "the slowest visa process in the world," often leading to frustrating delays and the need for temporary passes and special permits merely to venture outside the capital, Asmara. This formidable governmental control is pervasive, leading many to label Eritrea "the North Korea of Africa." The authoritarian regime tightly controls access, suppresses free speech, free press, and social media, and mandates military service that can extend for a lifetime, with travelers under constant surveillance. This pervasive oversight is mirrored in the nation's digital landscape, where internet access harks back to the 1990s, requiring scratch cards and offering connections so sluggish that sending a single email can take minutes. Economically, Eritrea operates as a 100% cash-only society, rendering ATMs, credit cards, bank transfers, money apps, and even mortgages non-existent.

This "old school" sensibility extends to daily life, as Binsky witnessed in an Asmara bowling alley where scoring is manual and pins are reset by hand by children, creating an atmosphere where one feels "like you're living five decades ago". Locals acknowledge this reality, with one resident remarking, "everything is the old type... but, uh, we enjoy it".

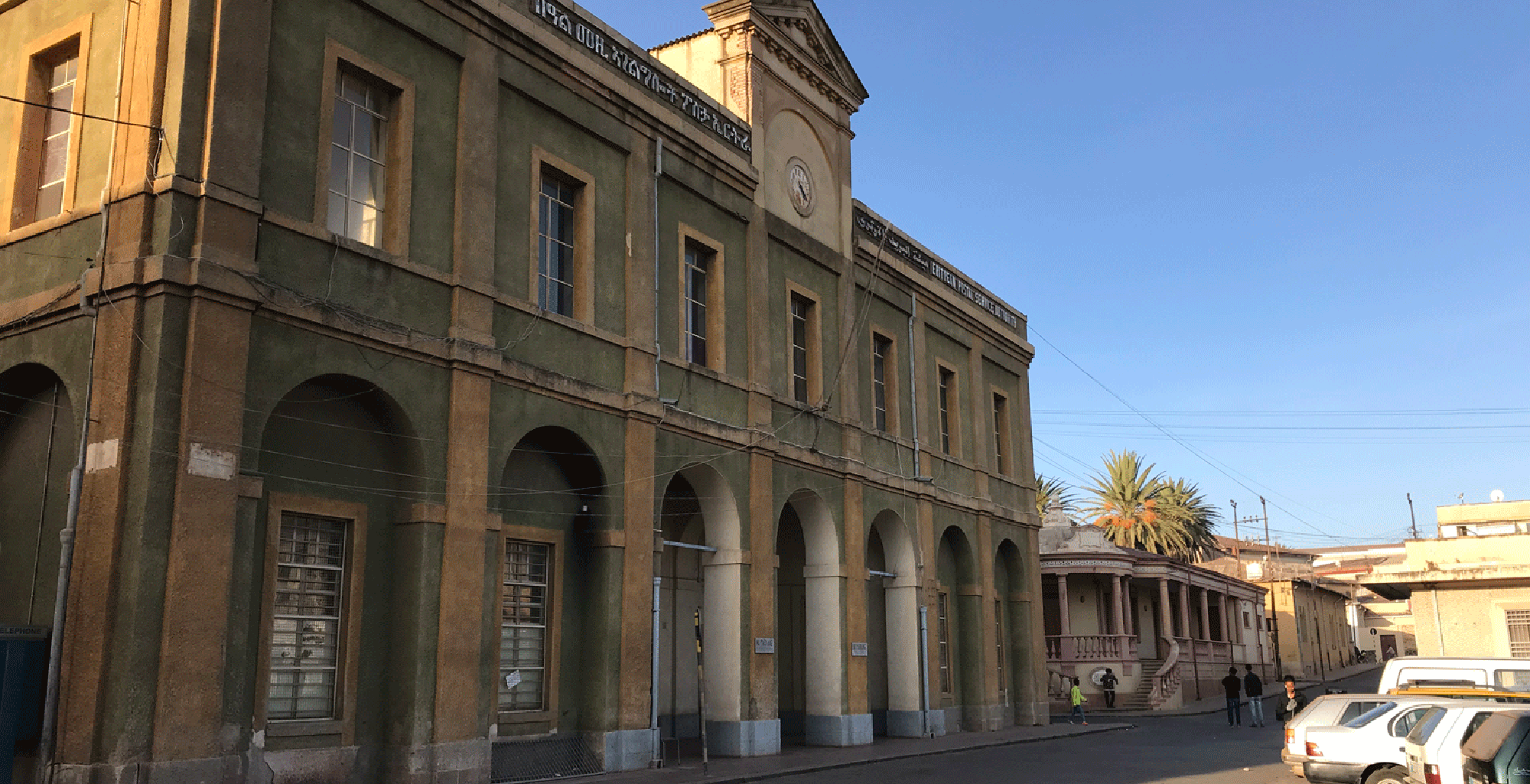

Despite its modern-day isolation and rigid controls, Eritrea bears a fascinating and persistent imprint of its colonial past. As a former Italian colony, Italian culture surprisingly thrives, evident in locals who speak fluent Italian, the nation's distinct architecture, and, notably, its coffee culture. Given that original coffee hails from neighboring Ethiopia and the historical Italian presence, Binsky suggests Eritrea might be "the best coffee country in the world," describing a macchiato as "the absolute best cup of coffee I've had in my entire life". Italian influences also extend to the availability of gelato and the predominantly Christian religious landscape, a striking feature given Eritrea is surrounded by Muslim countries like Egypt, Somalia, and Djibouti.

Related article - Uphorial Radio

Eritrea east coast of Africa

Eritrea's path to its current state has been one of enduring struggle. After 350 years of colonization under various powers—including the Ottomans, Egyptians, Italians, and Ethiopians—the nation finally gained independence in 1991. However, this freedom was soon overshadowed by a brutal conflict with Ethiopia in 1998, which claimed tens of thousands of lives and left tensions frozen for two decades. Since independence, President Isaias Afwerki has presided over a "tightly controlled one-party state," leading to the stark conclusion that "Eritrea still isn't free". Visible reminders of these conflicts are etched into the landscape, such as a massive tank graveyard from the Ethiopian war, where thousands of tanks are left "as is" in nature as poignant "memories". Similarly, the port city of Massawa, a site of numerous colonial occupations and a significant battle in 1990, still bears the scars of history, with many buildings left in their war-damaged state. A local's profound statement that "peace is a very important thing" resonates deeply, reflecting the nation's turbulent past.

Yet, amidst the stringent controls and infrastructural challenges, the most defining and ultimately cherished characteristic of Eritrea, as documented by Drew Binsky, is the profound warmth and resilient spirit of its people. Hospitality is exceptional, with locals eager to share their culture and food. Experiences ranged from being invited into a village home for a traditional coffee ceremony by a sweet widow raising nine children on her own, a moment Binsky describes as a "beautiful" and "special experience", to sharing spicy "Ful" and sweet honey with friendly restaurant owners. Journeys beyond Asmara, such as to Keren, the second-largest city, reveal a more tribal and authentic community, known for its enormous camel and livestock markets. Here, life is often basic, "without Internet, running water," yet characterized by a "simple, peaceful life and lots of smiles". A remarkable encounter included an 11-year-old boy named Abdul Maji, who spoke seven languages—learned through offline apps on a Chinese-assembled phone—and guided Binsky to a local tribal wedding. This wedding was a vibrant display of communal celebration and ritual, featuring traditional attire, separate dancing for men and women, and the communal sharing of fermented beer. A unique cultural observation noted was the absence of smoking among Eritrean people, considered a sign of respect. While the initial encounter with Eritrea might feel undeniably strange and rooted in a bygone era, the overwhelming and lasting impression, as Drew Binsky concludes, is the "incredible warmth" of its people, who are universally described as "kind, welcoming and proud of their culture". This deep-seated hospitality and resilience, against a backdrop of historical strife and governmental oversight, becomes the most cherished memory of this enigmatic land.