The International Center of Photography in New York inaugurates its new Lower East Side location with CONTACT HIGH: A Visual History of Hip-Hop. The exhibition, based on Vikki Tobak’s eponymous book published in 2018, documents the explosion of hip-hop in the United States through a series of iconic portraits. These original images break with the stereotypes of a raucous, disorderly culture.

Janette Beckman, “Ladies of Hip-Hop” for Paper magazine, Manhattan, 1988

The exhibition’s opening images show groups of African Americans in public spaces or recording studios, and it takes a while to spot a familiar face in the crowd. The shots are spontaneous, taken in the swing of things during an afternoon spent among friends. These are the early days of hip-hop—an interdisciplinary group phenomenon (including dancers and DJs, graffiti artists and singers), centered around some disadvantaged neighborhoods in Los Angeles and New York. As far as iconic sites, the exhibition insists on regional differences and the influence of other cities.

Documenting hip-hop

As the exhibition unfolds, the images zoom in on single figures. We encounter Tupac, Salt-N-Pepa, Kool Herc, and Lauryn Hill, among others—the list is long. We also recognize some of the most iconic portraits, which we have seen in the media again and again and which have shaped the image of the hip-hop scene, tracing its development both as a musical genre and as a fashion statement in the form of streetwear. Dapper Dan’s jacket, on display in the exhibition, reminds us that these stars singled themselves out by shedding their backgrounds even as they reclaimed them to reinvent themselves as true works of art. While their songs were about life, the photographs and costumes were the visual symbols of their assertiveness, emancipation, and adherence to their own codes.

Janette Beckman, Salt-N-Pepa, Shake Your Thang, New York City, 1987. © Janette Beckman, Courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Political impact

The exhibition showcases many never-before-seen images and contact sheets by photographers like Barron Clairborne and Janette Beckman who poured out the contents of their storage boxes. In addition to affording us the pleasure of taking a peek behind the scenes and bringing us face to face with celebrities, the contact sheets offer a glimpse of the image selection process. The choices made by the photographers were certainly deliberate: they reveal a clear intention as to how they wanted these music icons—some well-known, others up-and-coming—to be seen. They seem to have been aware of the place their photographs would come to occupy in the collective imagination.

In a handful of images, we discover Biggie (as the rapper Notorious B.I.G. was fondly known) wearing a crown, walleyed, and somewhat shy, as if he were trying to escape his own notoriety. Other shots suggest hesitation, uncertainty, even as they emanate lightheartedness and sincere camaraderie. In retrospect, it might seem that the choice of images was an eminently political gesture aimed at societal issues such as discrimination, racism, and the perception of black men and women. In effect they helped to forge a sort of prestige, but above all they celebrated figures from working-class and, more importantly, African American backgrounds. These images were duty-bound to show a certain America—the America of the Bronx, Harlem, and Brooklyn—in the best light, and the photographers grasped this idea from the very start.

Al Pereira, Queen Latifah on the set of Fly Girl, New York City, 1991

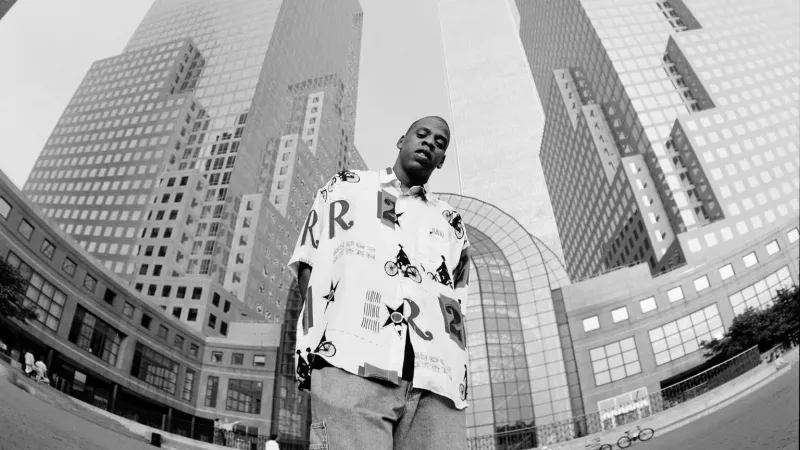

Barron Claiborne, Biggie Smalls, King of New York, Wall Street, New York, 1997

Ithaka Darin Pappas, Eazy-E, Skate Outta Compton, Venice Beach, Los Angeles, 1989

Ricky Powell, New York Street Culture, New York City, 1980s and 90s

Jayson Keeling, Lauryn Hill

Janette Beckman, Slick Rick, Manhattan, 1989. © Janette Beckman, Courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Jamil GS, Jay-Z’s First Photo Shoot, New York City, 1995