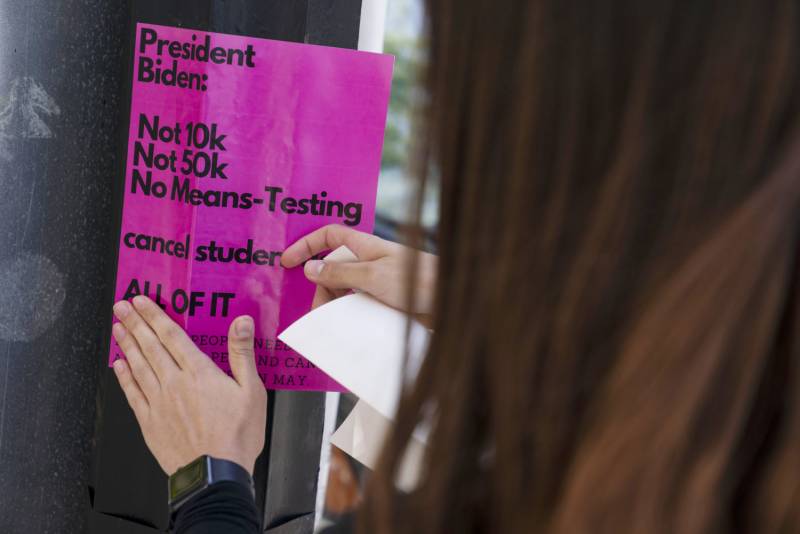

Over the weekend, various news organizations reported President Joe Biden is getting closer to some flavor of student debt reduction. This is a great topic for journalists covering midterm Congressional races to ask candidates about.

The Hill reports, “President Biden plans to move forward with student loan debt forgiveness, with two sources telling The Hill he is considering action to expunge at least $10,000 per borrower.”

The Washington Post says, “The White House is considering income caps for eligibility for student loan relief that would exclude higher-earning Americans, as President Biden nears a decision on the matter, according to three people aware of administration discussions.”

So far, President Biden has resisted calls by Democratic congressional leaders to cancel up to $50,000 in student debt for some and maybe all of the 43 million federal student loan borrowers. Debt forgiveness of no more than $10,000 attached to some stipulations about household income limits has more backing than the numbers advocated by top Democrats.

It is not entirely clear whether the president has the authority to cancel student debt. The Justice Department is looking into the question.

Legal experts at Harvard explored the question after Sen. Elizabeth Warren floated the idea a couple of years ago. They found that the Higher Education Act seems to give a secretary of education (who works for the president) the power “to create and to cancel or modify debt owed under federal student loan programs.” And, the experts said, “We conclude that your proposal calls for a lawful and permissible use of the authority Congress has conferred on the Secretary of Education, which is anticipated and allowed for in the budgetary and accounting treatment of federal student loan programs.”

NPR also took a deep dive into the president’s authority to forgive student debt and reached the same conclusion as the Harvard experts.

Even if Biden could cancel massive amounts of student debt, should he?

The answer has many layers. One is economic, one is philosophical and, of course, there are political considerations. After all, Biden and Democrats made promises in 2019 to do something to help burdened borrowers with student debt. But then, is it fair to people who have struggled for years, even decades, to repay their student debt if others who went to a school they could not afford get a free ride? Shouldn’t we encourage all students to get a higher education because it will benefit everyone?

In February 2021, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said, “The president has and continues to support canceling $10,000 of federal student loan debt per person as a response to the COVID crisis.” At the same time, Sen. John Thune (R-SD) said forgiving unpaid college loans would be “incredibly, fundamentally unfair” to students who have already repaid their debts.

The Committee for a Responsible Budget says canceling student debt would add to inflation, and inflation is a red-hot hot button for voters.

CRB argues, “Besides adding $1.6 trillion to the national debt and disproportionately benefiting higher-income individuals, we find student debt cancellation would cause prices to increase faster than they already are, exacerbating inflationary pressures.”

The foundation of that argument that debt forgiveness would benefit richer white Americans is found in the fact that people working in higher-income positions — for example, doctors and lawyers — took on a significant amount of student debt attending graduate and post-graduate school. The Brookings Institute says 56% of the outstanding student debt is owed by households that hold graduate degrees.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York spelled this out in a study that shows lower-income households would not benefit nearly as much as higher-income households

Here is CRB’s calculation. I am going to leave the footnote annotations on their post so you can dive deeper into their reasoning that canceling debt would lead to inflation:

Full debt cancellation would cost the federal government roughly $1.6 trillion, while improving household balance sheets by a similar amount. Consistent with our prior analysis, we estimate this would translate to an $80 billion reduction in repayments in the first year, which would in turn increase household consumption by $70 to $95 billion once the effect of higher wealth is considered.

Often, higher consumption leads to higher economic output.1 However, the economy is currently unable to meet existing demand in light of elevated disposable income, strong balance sheets, lingering supply constraints, and other factors. This disconnect helps to explain the why the inflation rate hit a 40-year high in the past year, and why further increasing demand could result in higher prices rather than higher output.

In other words, the analysis says that if you cancel debt, people will have more money to spend, and they will spend it, driving up the demand for all kinds of goods and services. That demand would lead to shorter supplies and that would drive up inflation. It is similar to the effect that COVID-19 era stimulus programs created when households found themselves with unexpected money to spend, except for the households that needed the money to survive the pandemic.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York explains the complexities of loan forgiveness. For one thing, there are different kinds of student loans:

Calls for student loan forgiveness entered the mainstream during the 2020 election with most proposals centering around blanket federal student loan forgiveness (typically $10,000 or $50,000) or loan forgiveness with certain income limits for eligibility. Several studies (examples here, here, and here) have attempted to quantify the costs and distribution of benefits of some of these policies. However, each of these studies either relies on data that do not fully capture the population that owes student loan debt or does not separate student loans owned by the federal government from those owned by commercial banks and are thus not eligible for forgiveness with most proposals.