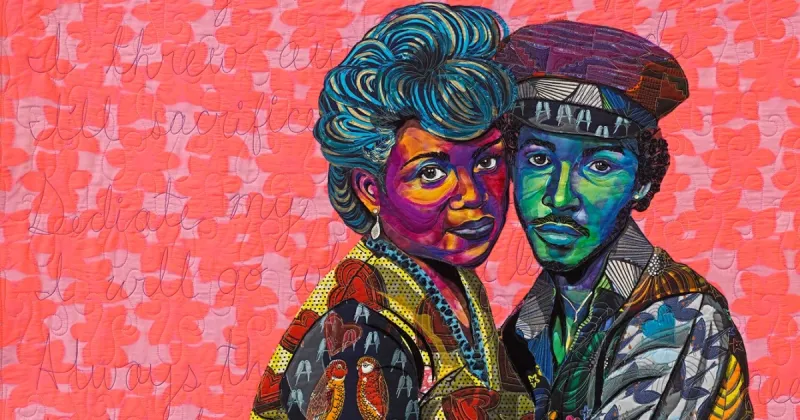

Sokari Douglas Camp laughs as she says she is "amazed that there is still money being spent on my work". The Nigerian-born artist is one of the world's most prominent sculptors, and her giant steel creations have dominated spaces in leading galleries, museums, and collections around the world. Her pieces have even been exhibited at the Houses of Parliament. Some of Ms Douglas Camp's work is currently on display at London's Victoria and Albert Museum - next to a Rodin.

Read Also: 5 Signs You Are Not Made To Be A Computer Programmer

So it perhaps shouldn't be such a surprise that her sculptures, which sell for tens of thousands of pounds, have been attracting attention from institutions and individuals with deep pockets. She half-jokingly describes herself as "having a moment", despite having a career spanning back to the 1980s. "City bank clients have come in and said 'I want to buy this, this and this'. Or somewhere like the British Museum wants to buy this or that, and you think - wow!"

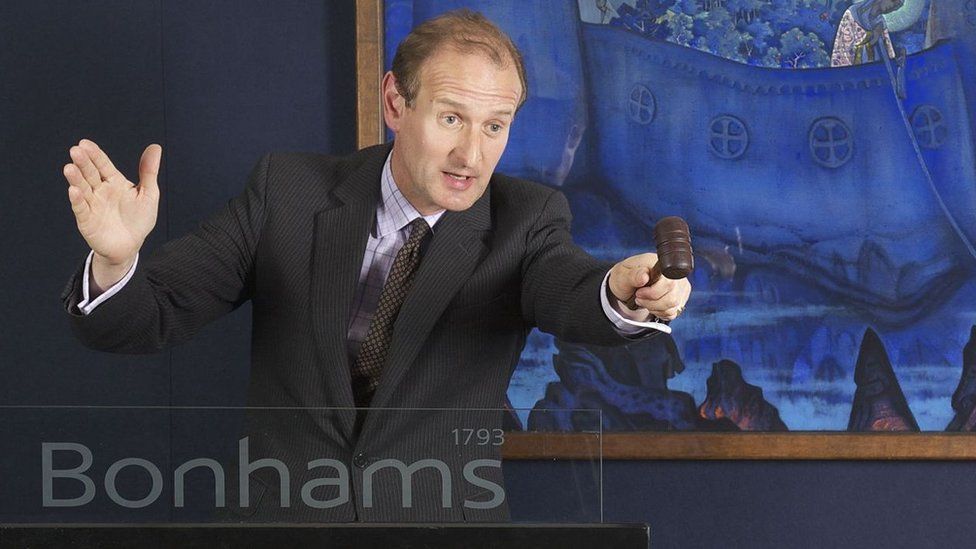

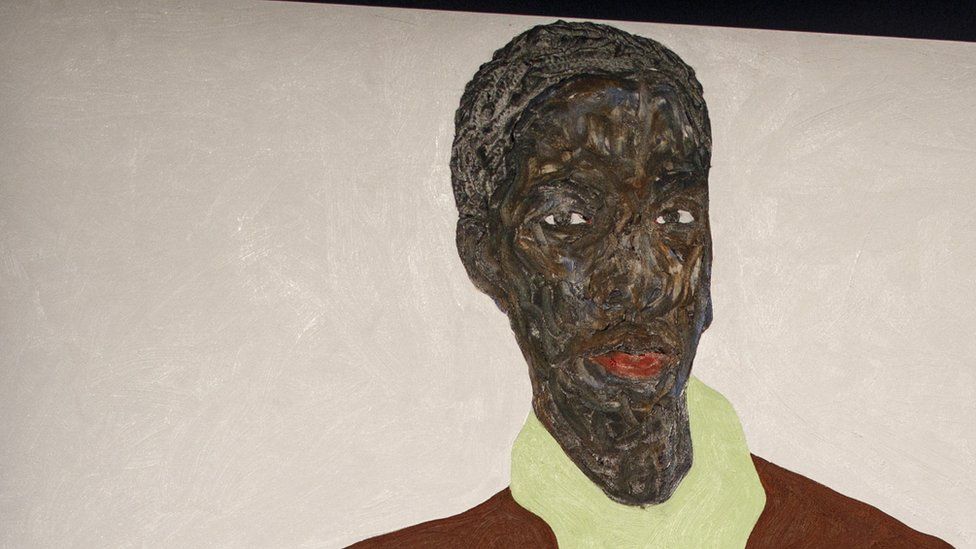

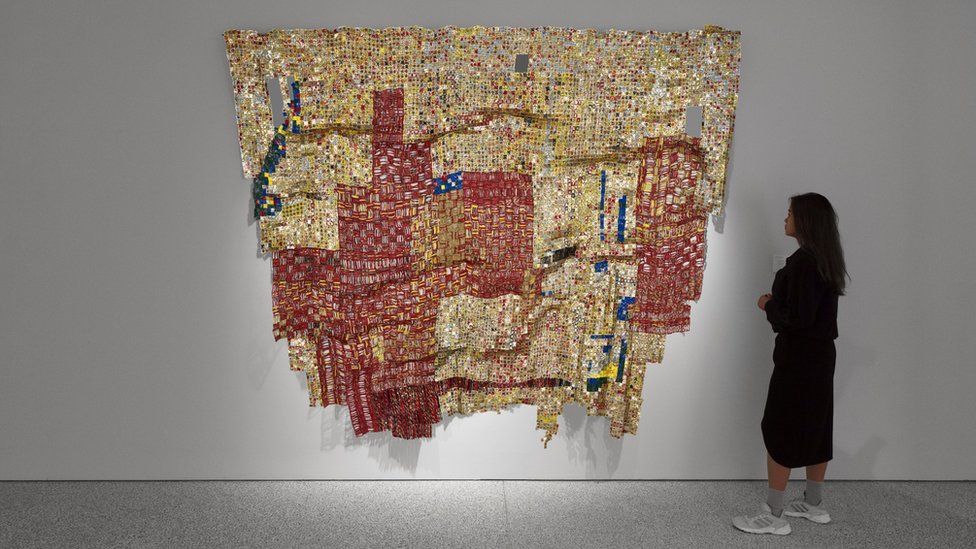

Contemporary art is considered to be worked by living artists, or those who have died in recent years. Whereas, modern art typically applies to work from the 1880s to the 1970s. Ms Douglas Camp is not the only contemporary African artist who's been enjoying a surge in interest. The value of auction sales of contemporary and modern African art surged by 44% to a record high of $72.4m (£65.6m) last year, according to consultants ArtTactic. That $72.4m may still be a relatively modest proportion of the $2.7bn sales of all modern and contemporary art at auction in 2021. But some experts say that, despite increased demand, African art is still under-priced and that's attracting a lot of attention. "The aesthetic qualities my pieces have are definitely foreign from other western ideas," says Ms Douglas Camp. "It takes a long time for the West to accept that other people have ideas, or have worthy cultures and traditions." Giles Peppiatt, director of modern and contemporary African art at auctioneers Bonhams, is one of the leading lights in the field. His last auction attracted bids from around the globe, with interest from the Far East being particularly strong.

"It is a very hot market," he says. "There are works by African artists that are fetching over £1m, and other works by African artists fetching £500,000 that a few years ago were only fetching £10-15,000." At the very top of the market, the auction prices can be even greater. For instance, a painting by Ghanain artist Amoako Boafo sold for $3.4m in Hong Kong at the end of 2021 - more than 10 times the expected price. "The best and the finest works tend to appreciate the most," says Mr Peppiatt. So what's driving the market? Mr Peppiatt says that major international institutions like the Tate in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, are racing to make up for years of neglecting the sector.

Counterintuitively, the economic chaos caused by the pandemic may also have helped boost interest from wealthy collectors. "Investors of that nature don't want to keep cash," says Mr Peppiatt. "They were getting nothing for it in the bank. So they bought art." The rapid expansion of online auctions and promotions on platforms like Instagram have also helped by boosting the exposure of African artists. But having your work sell for big prices at auction doesn't mean an artist can immediately break out the champagne. Artists usually sell their work via a gallery, which exhibits and markets their art. The gallery typically takes around 50% of the sale price.

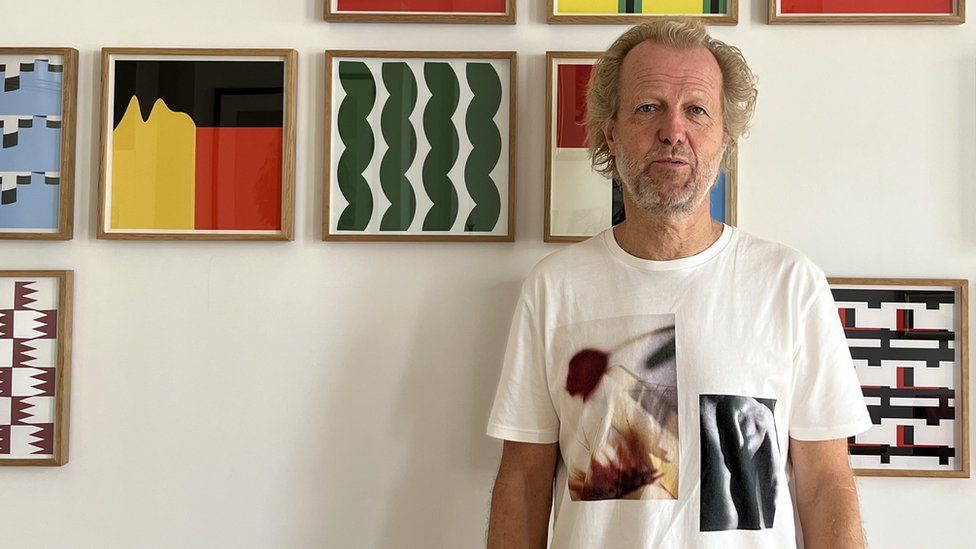

If a buyer sells the piece again and perhaps doubles their money, the artist will see little of that profit. In Europe the maximum royalty fee payable to the creator of the work is 4% of the sale price at auction. High auction sale prices may mean your gallery is able to charge more for your other work, but the increase there is unlikely to be stratospheric, according to Mr Peppiatt. Owning around 500 pieces of contemporary and modern African art, UK businessman Robert Devereux is a prominent collector. He has some at his home, loans out others, but much is kept in storage.

"Even if it's a disappointment," says Mr Devereux of his own sale at Christie's, "it will certainly generate a lot more than it cost me to buy them" . Established African artists are also trying to help the next generation come through across the continent.