Decolonization is often described as a turning point in global history, but how much did it really change? In a recent lecture at Gresham College, historian Martin Thomas examined the deeper realities of post-imperial transitions, questioning the popular narrative of a world fundamentally transformed.

Thomas begins by acknowledging the sheer scale of political change: from the American Revolution in 1776 to 1976, over 160 dependent territories either achieved sovereign independence or were assimilated into larger states. This process, the disintegration of European overseas empires, is often described as decolonization, and some scholars conceptualize it as "an apparatus for the serial production of sovereignty". However, Thomas immediately introduces a critical caveat: the reality of such sovereign independence remains deeply contested. He argues that simply equating decolonization with a shift from foreign to local rule is "analytically limiting" because the antecedent colonization left indelible "imprints in patterns of inequality in degraded environments and in systems of belief that couldn't be undone by a simple handover of political power". What some call "uncolonizing" is a far more gradual, complex process, one that, particularly for indigenous peoples of the 'fourth world,' remains "very substantially unrealized".

The lecturer further explains that the term "decolonization" itself didn't gain common currency until after World War II and was not widely used even at the height of the process in the 1950s and 1960s. Instead, decolonization was a dynamic process involving "several moving parts," including the withdrawal of European rule, the rise of anti-colonial nationalists, the pressures of Cold War rivalries, and the assertions of minority groups within newly decolonizing states. Anti-colonialism, Thomas suggests, makes sense as a unifying abstraction—an expression of opposition to an "ethically indefensible" system, rather than unswerving support for a particular national form. He notes that in the contemporary public sphere, decolonization is increasingly associated with calls for an overhaul of public culture, from place names and statues to museum holdings and academic curricula, signifying a demand for "attitudinal change toward histories that societies...find pretty difficult to confront". Thus, decolonization emerges as "at once a political form and a cultural phenomenon," far "more varied, more complex and less complete than old narratives of transfers of power might suggest".

A significant theme explored by Thomas is the intrinsically global nature of anti-colonial movements. He highlights how anti-colonialists organized "transnationally," across frontiers and empires, as exemplified by a 1960s photograph from newly independent Algeria showing figures like Nelson Mandela and leaders of the MPLA. Yet, paradoxically, these newly independent territories commonly asserted their right to "national self-determination," a concept which Thomas points out is often understood as a "projection of western thinking". He questions its universal applicability, asking what truly constitutes a "community" or "people" worthy of self-determination, and whether its precepts are fairly applied within societies internally divided by ethnicity, politics, or religion, let alone by gender, sexuality, or class. He argues that the process of decolonization "isn't done" because it "failed to do" many things, leaving the pillars of self-determination, domestic jurisdiction, and territorial integrity continually challenged, leading some to suggest we live in a "new imperial age".

Related article - Uphorial Radio

Economically, Thomas posits that decolonization was "less transformative economically than they were politically culturally or ecologically". The eclipse of colonial governance did not "transform life chances overnight," with patterns of unequal trade, debt burdens, externally imposed structural adjustments, and environmental degradation persisting. The "north south geometry of global capitalism" remained largely unchanged, further highlighted by the post-WWII Bretton Woods system and the emerging international law that, despite edging towards repudiation of colonialism, still assigned the decolonizing world "junior status".

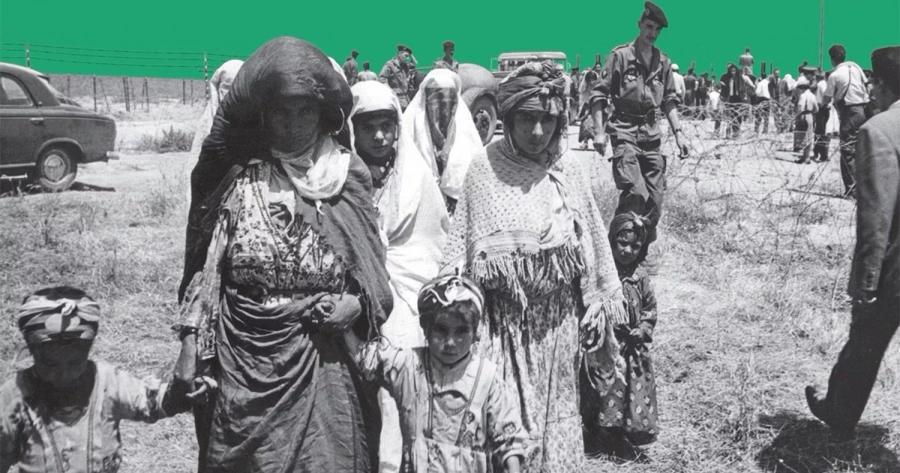

The role of violence in decolonization also receives Martin Thomas's close attention. While it appears "pretty obvious that decolonization was a violent business," encompassing numerous wars and the "worker day violence of exclusions, compulsions, indignities and arrests," he questions whether violence was the "motor" or merely "one of many different sorts of fuel" for change. He cautions against focusing solely on organized violence, as it risks obscuring "the many nonviolent debates and at least relatively nonviolent spaces that were part of the decolonization story". Anti-colonial claims were also articulated through imaginative organizational forms, such as the "guerrilla diplomacy" of Third World conference cultures like Bandung and Havana, which lent "a much sharper ideological edge to decolonization".

This ideological sharpness culminated in "radical third worldism," which, according to Thomas, peaked during what he calls the "long 1960s"—from the Cuban Revolution in 1959 to 1974. This era saw a confluence of anti-imperialism and new leftist politics, with internationalist-minded anti-colonialists congregating in non-European cities, advocating for a "new international economic order" (NIEO). The recognition among leading political actors was that "political independence just was not enough"; it had to include the capacity to sustain human security and economic rights, which were compromised by a global economic order that condemned third-world states to "subservience to the rich world's economic demands". However, the NIEO ultimately failed in 1974, not least because it "never represented a sustainable coalition" of member states ranging from socialist experimenters to ultra-capitalist oil producers, and global financial and trading systems remained "stacked against them".

Finally, Martin Thomas highlights a "curious absence" in studies of decolonization: its intricate partnership and relationship with globalization. While decolonization might be seen as a disintegrative process, globalization, often led by the United States, leveraged it as an "integrative process," welding the world together through market access, transmigration, and new cultural connections. The acceleration of mass consumption and changing global trade rules had profound implications, meaning that "straightforward transfers of power between a single ruling empire and a dominant anti-colonial movement were never really total". Economic connectivity, capital movement, communications links, and migratory flows defied revolutionary visions of a postcolonial world, reinforcing "inequalities in the distribution of global power between north and south". Anti-colonial modernizers, in their pursuit of development and renewal, inadvertently became "part of the problem" by critically depending on foreign money, expertise, and loan capital, which "sustained forms of influence and obligation that jarred with those assertions of sovereignty".

In conclusion, Martin Thomas asserts that while empires have indeed ended, the world has not been fundamentally remade. The socioeconomic markers of 21st-century colonialism persist in vast discrepancies of life expectancy, poverty rates, and life chances between the rich and poor global regions. Furthermore, cultural legacies of colonialism, such as casual racism and the marginalization of ethnic, religious, or low-income groups from narratives of rich world politics, underscore that "the end of empires did not remake the world".